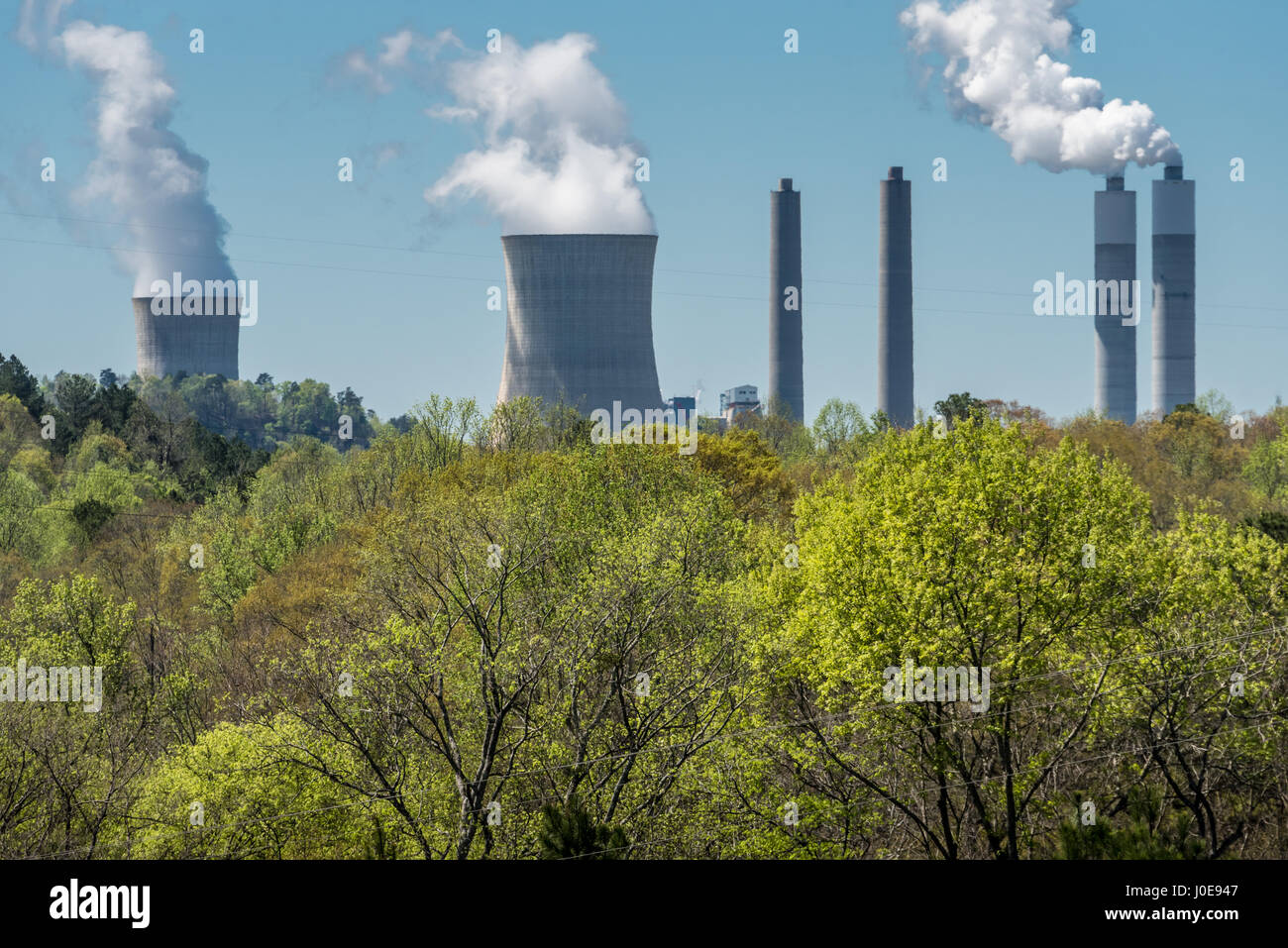

Drive about 20 miles northwest of Birmingham and you can't miss it. The massive cooling towers of the James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant dominate the skyline near Quinton, Alabama. It’s a beast. Seriously. We’re talking about one of the largest coal-fired power plants in the entire United States. While the rest of the country is sprinting toward renewables, Miller—as locals call it—remains a foundational pillar of the Southern power grid. It’s massive. It’s controversial. And honestly, it’s a bit of an engineering marvel if you can get past the politics of coal.

Owned and operated by Alabama Power, a subsidiary of the utility giant Southern Company, the plant sits right on the Locust Fork of the Warrior River. It doesn't just provide "some" power; it churns out a staggering 2,640 megawatts of electricity. That is enough juice to power well over a million homes. If you live in Alabama or parts of Georgia and Mississippi, there is a very high probability that the light you're reading by right now started its life as a piece of coal inside one of Miller’s four massive units.

The Massive Scale of the James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant

Let’s talk numbers for a second because the scale is hard to wrap your head around without them. The facility is split into four distinct units. Units 1 and 2 came online in the late 70s and early 80s, while 3 and 4 followed in 1989 and 1991. It represents the pinnacle of late-20th-century coal technology. You’ve got these four boilers that are basically the size of skyscrapers.

The fuel demand is incredible. Every single day, multiple trains—some over a hundred cars long—pull into the facility. They’re hauling sub-bituminous coal, mostly from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. Why Wyoming? It burns cleaner than a lot of the high-sulfur coal you find closer to home in the Appalachians. It’s a logistical nightmare that Alabama Power has turned into a science. The coal is pulverized until it’s as fine as face powder, then blown into the furnaces to create the heat that drives the steam turbines.

Efficiency is the name of the game here. Despite its age, Miller is frequently cited as one of the most efficient coal plants in the country. It has to be. In a world where natural gas is cheap and solar is expanding, a coal plant only survives if it can produce electricity at a rock-bottom price point.

The Elephant in the Room: Carbon and Compliance

You can’t talk about the James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant without talking about emissions. It’s been a lightning rod for environmental groups for decades. According to EPA Data from the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, Miller has consistently ranked as the single largest emitter of CO2 in the United States.

That sounds bad. To be fair, it is a lot of carbon. But there’s a nuance here that often gets lost in the headlines.

The plant is the top emitter because it is one of the largest and most consistently running plants. It’s a "baseload" facility. Unlike some gas plants that only turn on when it’s hot outside, Miller runs nearly 24/7. When you produce that much power, the raw numbers for emissions are going to be high. Alabama Power has dumped billions—literally billions—into scrubbers and Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) systems to strip out sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides.

Environmentalists, like those at the Black Warrior Riverkeeper, point to the coal ash ponds and the sheer volume of greenhouse gases as a reason to shutter the site. They argue that the transition to "clean" energy isn't happening fast enough. Conversely, the utility argues that you can't just flip a switch on a 2,600-megawatt plant without risking the stability of the entire regional grid. It’s a tense standoff.

Why Miller Hasn’t Been Decommissioned Yet

It’s actually pretty simple: reliability.

Battery storage isn't quite there yet for the scale Alabama needs during a "Polar Vortex" or a record-breaking summer heatwave. When the wind isn't blowing and the sun is down, you need rotating mass. You need those massive turbines at the James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant spinning to keep the frequency of the grid stable.

✨ Don't miss: Dollar vs Rupee Rate: What Most People Get Wrong About 90+

Economic impact is another factor. The plant is a massive taxpayer for Jefferson County. It employs hundreds of high-skilled workers—operators, engineers, welders, and chemists. If Miller closed tomorrow, the local economy in the Quinton and West Jefferson area would essentially crater. Alabama Power has signaled that they intend to keep these units running well into the 2030s, though they are constantly evaluating the "least-cost" path for customers.

How the Plant Works (The Simple Version)

Basically, it's a giant tea kettle. That's the best way to think about it.

- Coal Pulverization: Giant mills grind coal into dust.

- Combustion: The dust is blown into a furnace and ignited.

- Steam Generation: Water pipes surrounding the furnace get hot—really hot. The water turns into high-pressure steam.

- The Turbine: That steam hits the blades of a turbine, spinning it at 3,600 RPM.

- The Generator: The turbine is connected to a shaft with magnets. Spinning magnets inside wire coils create electricity.

- Cooling: The steam is cooled back into water using the river water (which never actually touches the coal or the "dirty" side of the plant) and sent back to the boiler to do it again.

It’s a closed loop for the working fluid, but the cooling towers are where you see that white "smoke" rising. Most people think that's pollution. Most of the time, what you’re seeing from the wide towers is just water vapor. Pure steam. The actual exhaust goes through the tall, skinny stacks after being scrubbed of most pollutants.

The Future of Alabama Power’s Largest Asset

Is there a world where Miller converts to natural gas? Maybe. We’ve seen it happen at other Southern Company plants like Plant Barry or Plant Gaston. Converting a coal unit to gas is usually cheaper than building a new plant from scratch, and it cuts carbon emissions by about half.

However, Miller’s specific design and its reliance on Wyoming coal make it a specialized beast. For now, the strategy seems to be "run it while it’s legal and affordable." The EPA’s 111(d) rules and other "Good Neighbor" regulations are making it harder, but Miller keeps chugging along.

It’s worth noting that the plant also serves as a testing ground for carbon capture technology. While not fully implemented on all units, the site has been involved in research to see if we can actually "catch" the CO2 before it hits the atmosphere. If that ever becomes commercially viable at scale, Miller could go from being an environmental villain to a savior of the coal industry. But honestly? That’s a big "if."

What This Means for You

If you're a ratepayer, Miller is the reason your power stays on when the weather gets nasty. It's the "old reliable" of the fleet. But you’re also paying for those billions of dollars in environmental upgrades through your monthly bill. It’s a trade-off. Reliability versus cost versus environmental impact.

The James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant isn't just a collection of steel and concrete. It’s the center of the debate over the American energy transition. You’ve got the undeniable need for massive amounts of power on one side and the undeniable reality of climate change on the other. Miller is exactly where those two forces collide.

Actionable Insights for Interested Parties

- For Residents: Keep an eye on the Alabama Public Service Commission (PSC) filings. This is where decisions about the plant's future—and your power rates—are actually made. They hold public meetings in Montgomery that are often live-streamed.

- For Energy Enthusiasts: If you want to see the scale for yourself, there aren't public tours anymore for security reasons, but the plant is visible from several public vantage points near the West Jefferson area. It's a lesson in industrial geography.

- For Investors: Monitor Southern Company’s (SO) ESG reports. They provide specific data on how they plan to de-carbonize their fleet and what the "terminal date" for coal assets like Miller might look like.

- Environmental Tracking: Use the EPA’s FLIGHT tool (Facility Level Information on GreenHouse Gases Tool) to see real-time, verified emissions data for the plant. It’s updated annually and gives you the raw data without the PR spin from either side.

Understanding the James H. Miller Jr. Generating Plant is the key to understanding why the energy transition is so much harder than just "building more solar panels." It's about infrastructure, jobs, and the sheer physics of keeping a modern society running. Whether you love it or hate it, Miller isn't going anywhere just yet.