If you walked into a Green Bay locker room in 1962 and asked who the toughest man on the planet was, nobody would’ve pointed at the guy with the biggest arms. They would’ve pointed at the guy with the 19-inch neck and the scowl that could peel paint off a barn. That was Jim Taylor. He didn't just play football; he committed it.

Most modern fans know the name Vince Lombardi. They know the "Packer Sweep." But honestly, that legendary play was basically just a fancy way to get Jim Taylor a head of steam so he could delete a linebacker from the census. He was the engine. He was the hammer.

Why Jim Taylor Green Bay Stats Still Shock People Today

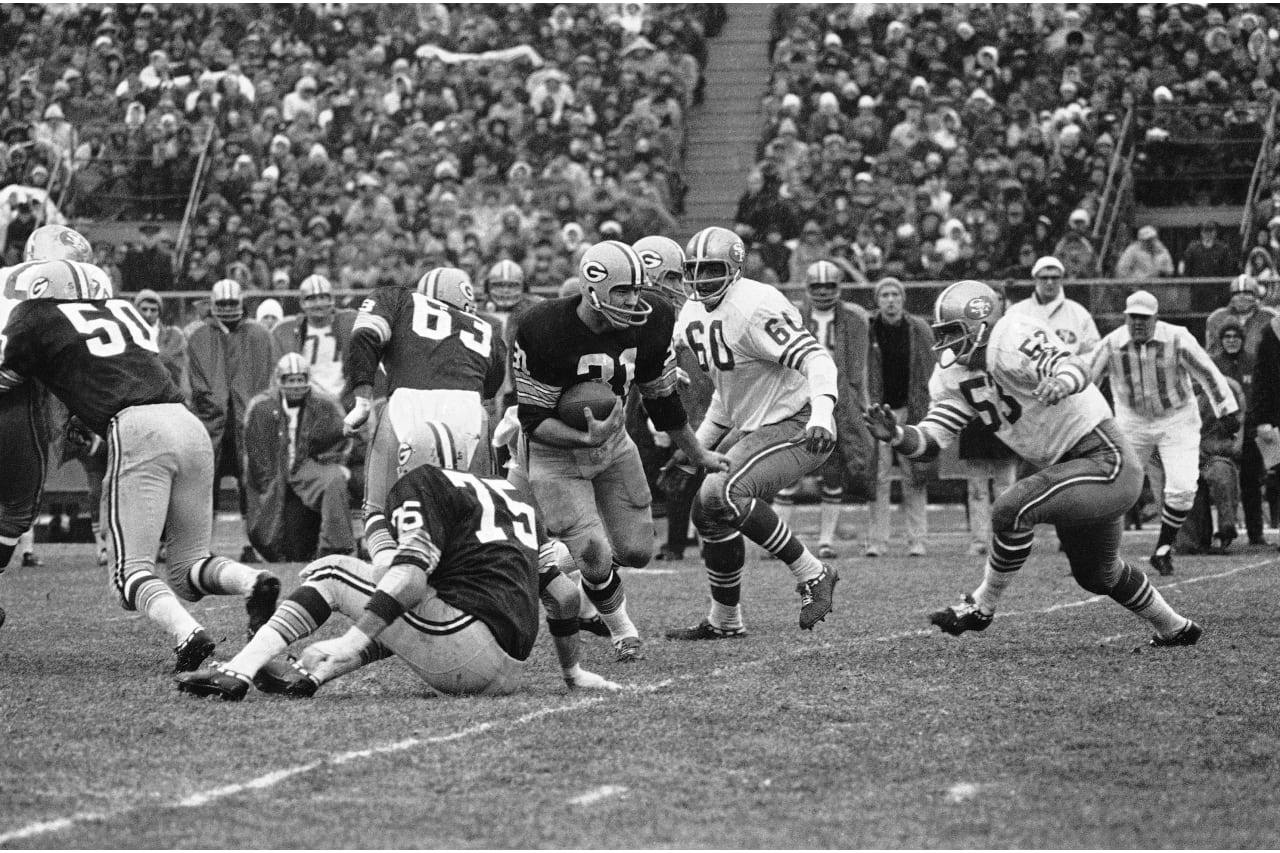

We live in an era of spread offenses and "load management." Jim Taylor would have hated that. During his peak with the Jim Taylor Green Bay years, the man was a volume machine. He was the first player in NFL history to ever post five consecutive 1,000-yard seasons. Think about that for a second. In an era with 12 or 14-game schedules, on frozen dirt, without modern cleats or high-tech recovery, he just kept coming.

The 1962 season remains his masterpiece. It’s the one year in a nine-year stretch where the great Jim Brown didn't lead the league in rushing. Taylor didn't just beat him; he took the crown by force. He finished with 1,474 rushing yards and 19 touchdowns. That touchdown record stood for 21 years until John Riggins finally broke it in 1983. Taylor wasn't just a "short-yardage guy." He was the entire offense when Paul Hornung was sidelined.

The Day He Became a Legend at Yankee Stadium

The 1962 NFL Championship game against the New York Giants is the stuff of nightmares. It was 13 degrees. The wind was gusting so hard the goalposts were shaking. The field was literally as hard as concrete.

Taylor took a beating that would have hospitalized a normal human. He bit his tongue early in the game and spent three hours swallowing blood. He had a gash on his elbow that required seven stitches at halftime. He came back out and kept running. He carried the ball 31 times for 85 yards and scored the Packers' only touchdown in a 16-7 win.

Sam Huff, the Hall of Fame linebacker for the Giants, famously said after the game: "Taylor isn't human. No human being could have taken the punishment he got today."

The Savage Rivalry With Jim Brown

There’s this weird misconception that Jim Taylor was just a "system" back because he played for Lombardi. That's total nonsense. Taylor and Jim Brown had a real, simmering rivalry. They were the two best fullbacks in the world, but they played the position completely differently. Brown was a gazelle with a jet engine; Taylor was a rhino with a grudge.

When the Packers played the Browns in the 1965 Championship, Taylor made it personal. It was Jim Brown's final game. Taylor outrushed him 96 yards to 50. In fact, in the three times they went head-to-head, Taylor outgained him twice and the Packers won every single game.

📖 Related: Where to Watch Diamondbacks vs Pittsburgh Pirates: No-Nonsense Guide for 2026

Lombardi once said you couldn't make a greyhound out of a bulldog. Taylor didn't want to be a greyhound. He took pride in the fact that he didn't run around people. He ran through them. He actually went out of his way to initiate contact with defensive backs just to let them know it was going to be a long afternoon.

More Than Just a Power Runner

- The Hands: People forget he caught 225 passes in his career.

- The Blocking: He was arguably the best blocking fullback of his generation, often clearing the way for Hornung.

- The Discipline: He fumbled only 34 times in over 2,100 touches. That’s a microscopic fumble rate for someone who invited that much contact.

- The Conditioning: He was a fitness freak long before it was cool. He lifted weights and did isometric exercises when other guys were smoking cigarettes at halftime.

The Move to New Orleans and the End of an Era

Things got kinda messy at the end. In 1967, Taylor played out his option and headed to the expansion New Orleans Saints. He was a Louisiana boy—born in Baton Rouge, a star at LSU—so going home made sense. But the Saints were an expansion team. They didn't have Jerry Kramer or Forrest Gregg pulling in front of him.

He managed 390 yards that year, which was a far cry from his glory days. When the Saints tried to put him on special teams during the 1968 preseason, he basically said "no thanks" and retired. It wasn't the cinematic ending he deserved, but his legacy was already set in stone. He was the first player from the Lombardi dynasty to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1976.

What You Can Learn From the Taylor Era

If you're looking to understand the DNA of the Green Bay Packers, you start with number 31. His "run to daylight" mentality wasn't just about finding a hole; it was about the sheer will to move the chains when everyone in the stadium knew he was getting the ball.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Study the 1962 Film: If you want to see what "physicality" actually means, watch the 1962 title game. It's a masterclass in grit.

- Compare the Stats: Look at Taylor's 1962 season ($1,474$ yards in 14 games) and compare it to modern 17-game totals. The efficiency is staggering.

- Visit the Hall: If you're ever in Green Bay, the Packers Hall of Fame has incredible exhibits on the "Thunder and Lightning" duo of Taylor and Hornung.

Jim Taylor passed away in 2018 at the age of 83, but he remains the gold standard for what a fullback should be. He didn't just gain yards; he took them.

To truly appreciate his impact, look at the career rushing leaders in Green Bay. For 43 years, nobody could touch his record. Ahman Green finally passed him, but it took a completely different era of football to do it. Even today, if you ask an old-timer at Lambeau about the toughest guy to ever wear the G, they won't hesitate. They'll tell you about the kid from Baton Rouge who bit his tongue, swallowed the blood, and kept running.