When you first sit down to watch Judas and the Black Messiah, there’s this heavy, vibrating tension that hits before a single word is even spoken. It’s not just a "movie." It feels like a haunting. Shaka King didn’t just make a biopic; he made a psychological thriller about the price of a human soul and the cold, calculated machinery of the American government.

Honestly, the most jarring thing about the film is how much of it is actually true.

🔗 Read more: Do Right: Why the Gospel-Pop Classic by Paul Davis Still Hits Different

We’ve all seen historical dramas that "beautify" the past or make the villains feel like cartoon characters. This isn't that. When Daniel Kaluuya—who absolutely deserved that Oscar—steps onto the screen as Fred Hampton, he isn't playing a saint. He’s playing a 21-year-old kid who was so terrifyingly articulate and charismatic that the FBI decided he had to die.

That’s the core of it. Twenty-one. Most of us at twenty-one are barely figuring out how to pay rent or pass a mid-term. Hampton was building a "Rainbow Coalition" in Chicago, uniting rival street gangs, Young Lords, and even working-class white Southerners under one banner. He was basically doing the one thing the powers that be always fear: he was uniting people across racial lines.

The Man Who Sold the Revolution

The "Judas" in the title is William O’Neal, played with a sort of twitchy, desperate brilliance by LaKeith Stanfield. If you think the movie exaggerated his betrayal, you’re in for a rough reality check.

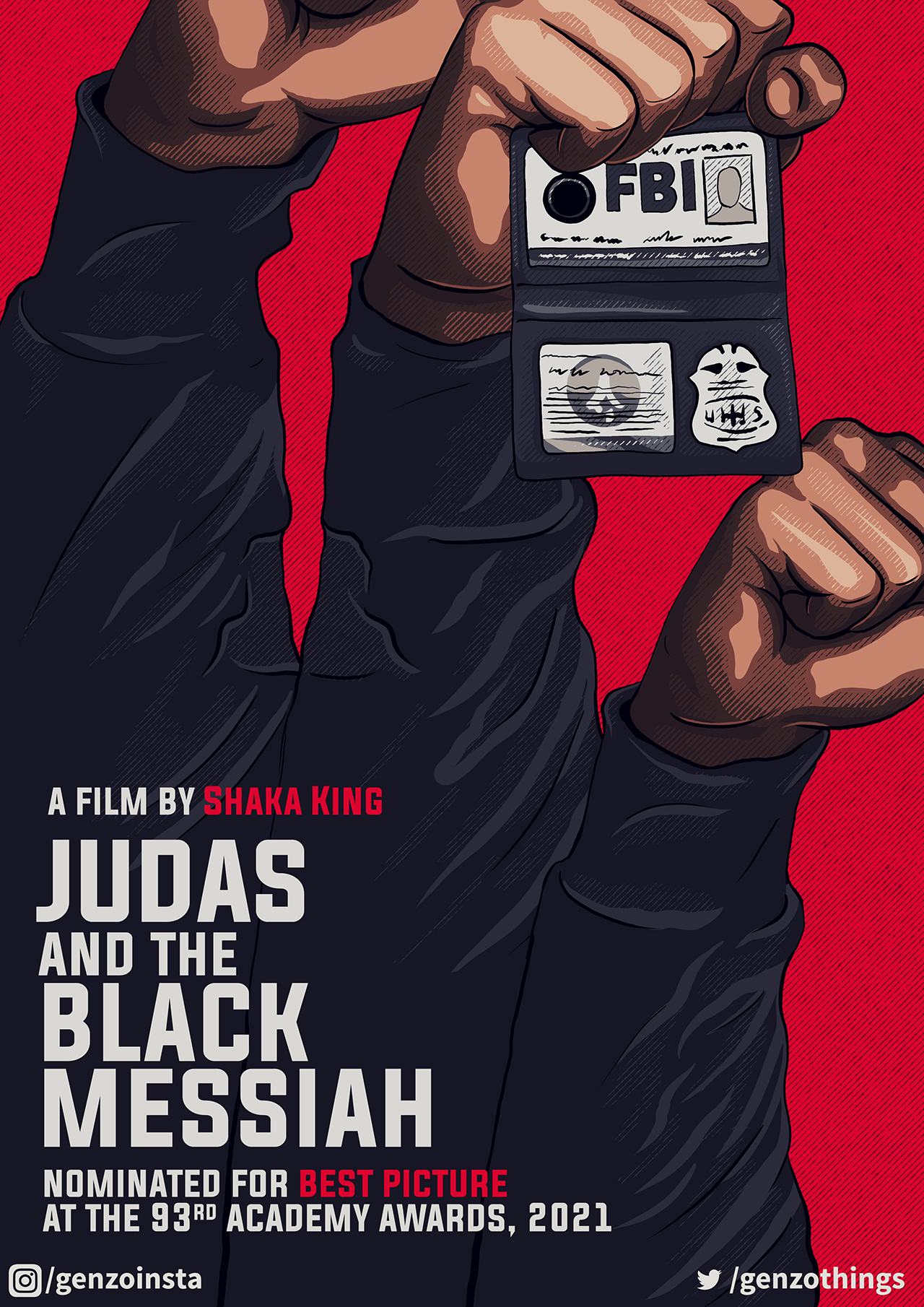

O'Neal wasn't some master spy. He was a teenager caught stealing a car and driving it across state lines. The FBI gave him a choice: go to jail or infiltrate the Black Panthers. He chose the badge. He famously said that a badge was "scarier than a gun," and he used that fear to burrow his way into the heart of the Illinois Black Panther Party.

He didn't just eavesdrop.

He became the head of security. He had the keys. He sat at the table while Hampton talked about revolution.

What the Movie Got Right (and What it Tweaked)

Let’s talk about the raid. It’s the scene that stays with you, the one that makes your stomach turn. In the film, we see O’Neal slip something into Hampton’s drink. This is a huge point of historical debate. While O’Neal denied drugging Hampton in his 1989 interview for Eyes on the Prize II, an independent autopsy found a massive amount of secobarbital in Hampton’s system.

🔗 Read more: Why Pulp His 'n' Hers Still Matters Three Decades Later

He was unconscious. He never had a chance to wake up.

The police fired nearly 100 rounds into that apartment. The Panthers? They fired exactly one. A single shot from Mark Clark’s shotgun, and even that was likely a "death spasm" after he had already been hit.

The movie shows the police executing Hampton while his pregnant fiancée, Deborah Johnson (now Akua Njeri), was in the next room. That’s not "Hollywood drama." That’s based on her own testimony. She heard them say, "He’s good and dead now."

- The Crowns: In the movie, Fred meets with a gang called the Crowns. In real life, these were the Blackstone Rangers. The FBI actually sent a fake letter to the Rangers' leader, trying to trick them into thinking the Panthers had a "hit" out on them. They wanted the gangs to kill Hampton so they wouldn't have to.

- The Car Theft: O'Neal really did get caught using a fake FBI badge to steal cars. That’s how Roy Mitchell flipped him.

- The Money: O'Neal didn't just do it for his freedom. He got paid. He was getting a monthly stipend and even got a $300 bonus for the floor plan that led to the assassination. Think about that. $300 for a man's life.

Why Judas and the Black Messiah Still Hits Hard

You’ve probably noticed that the film focuses a lot on the FBI’s COINTELPRO. It’s a mouthful of an acronym, but it stands for Counterintelligence Program. It was J. Edgar Hoover’s secret war on anyone he deemed a "threat" to the status quo.

The movie makes it clear that the government wasn't just watching; they were active saboteurs. They weren't trying to solve crimes. They were trying to "prevent the rise of a black messiah."

That's the real chill.

The film doesn't hide Hampton's politics, either. He was a socialist. He spoke openly about how capitalism was the root of the problem. Some critics felt the movie played it a bit safe with the depth of his Marxist-Leninist views, but Kaluuya’s speeches still carry the weight of that ideology. When he yells, "I am a revolutionary!" it’s not just a catchphrase. It was a death warrant.

✨ Don't miss: Why War Is Over Song John Lennon Still Hits Hard Decades Later

The Tragic Legacy of William O'Neal

The most haunting part of this whole story isn't even in the main runtime of the movie. It’s what happened after.

O'Neal lived in witness protection for years. He moved to California, changed his name, and tried to disappear. But he couldn't. He eventually moved back to Chicago. On January 15, 1990—the day the Eyes on the Prize episode featuring his interview aired—William O'Neal ran onto the Eisenhower Expressway and was hit by a car.

It was ruled a suicide.

The guilt, or the fear, or the weight of being "Judas" finally caught up.

How to Lean Into This History

If you finished the movie and felt like you only got half the story, you're right. No two-hour film can capture the complexity of 1969 Chicago.

Start by looking up the actual documentary footage of Fred Hampton. You can find his speeches on YouTube. Hearing the real voice—the cadence, the speed, the raw power—makes Kaluuya’s performance even more impressive because you realize how much he channeled the actual man.

Read The Assassination of Fred Hampton by Jeffrey Haas. Haas was the lawyer who fought for thirteen years to get the truth out about the raid. He’s the reason we have the FBI memos today.

Also, look into the Young Lords and the Young Patriots. The "Rainbow Coalition" wasn't just a term Jesse Jackson used later; it was a radical, dangerous (to the state), and beautiful attempt at solidarity that we rarely hear about in history books.

The best way to respect the history shown in Judas and the Black Messiah is to realize that the "Messiah" wasn't just a man—it was the idea that people, when they stop fighting each other, are the most powerful force on earth.

Don't just watch the credits roll and move on. Look up the 10-Point Program of the Black Panther Party. Compare it to what communities are asking for today. You'll find that the "messiah" might be gone, but the message is still very much alive.