March 15, 44 BCE. The Ides of March. We’ve all heard the date, and we’ve all seen the paintings of a bunch of guys in bedsheets stabbing a dude in a hallway. But let's be real—the Hollywood version of Julius Caesar: how he died usually skips over the weird, messy, and honestly confusing details of what actually happened in the Theatre of Pompey that morning. It wasn't just a political assassination. It was a chaotic, disorganized bloodbath that almost went wrong about a dozen times before the first blade even touched him.

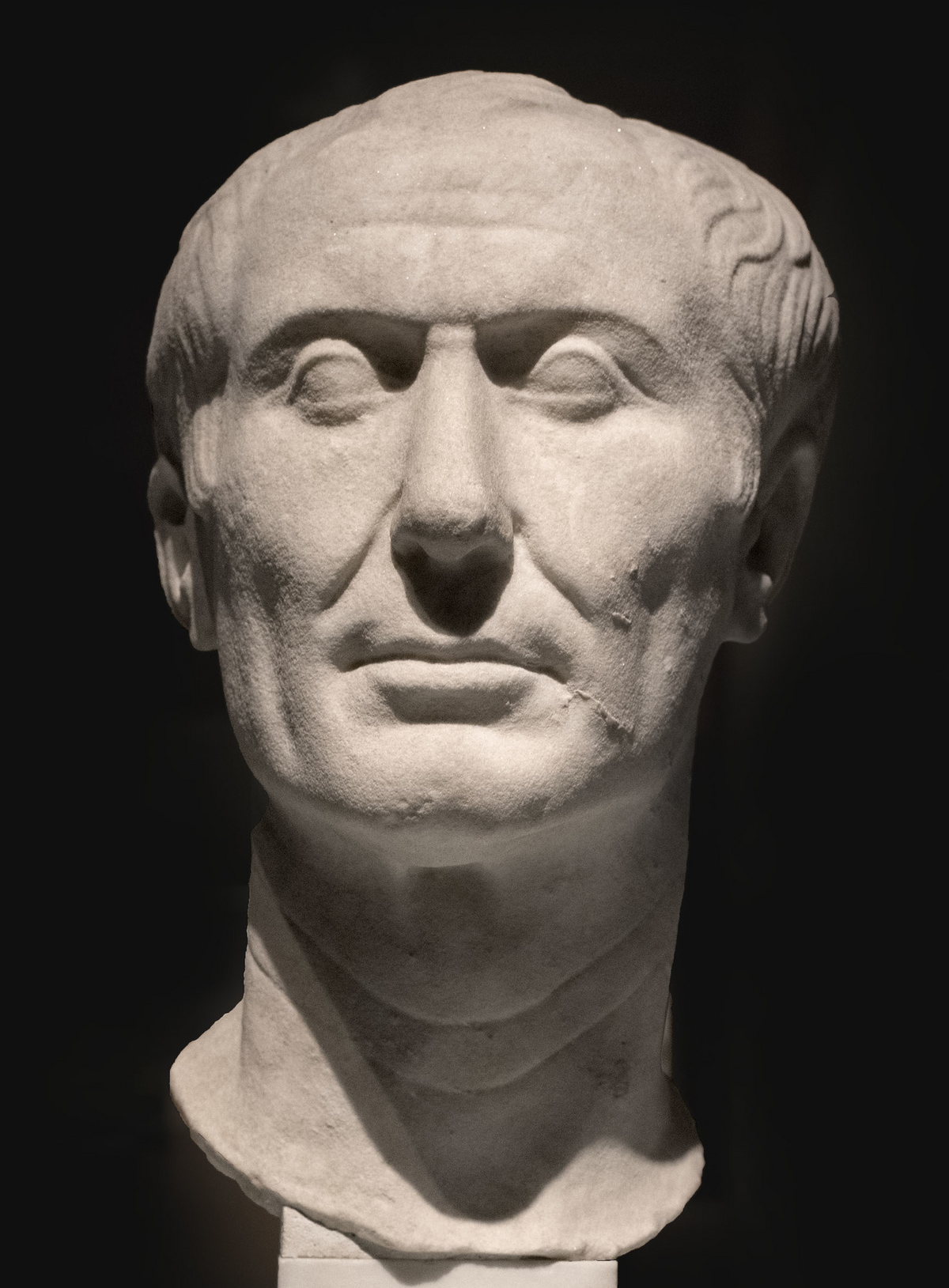

Caesar was a man who basically thought he was invincible. He’d just been named Dictator Perpetuo (dictator for life). He was planning a massive invasion of Parthia. He’d even dismissed his Spanish bodyguard because he thought nobody would dare touch him in Rome. Big mistake. Huge.

The Morning Everything Went Sideways

Honestly, the whole thing almost didn't happen. Caesar woke up feeling pretty rough. His wife, Calpurnia, had spent the night having nightmares about him being murdered, and she was practically begging him to stay home. Caesar, being Caesar, was inclined to listen to her until Decimus Brutus—not the famous Marcus Brutus, but a different guy Caesar actually trusted—showed up at his house. Decimus basically teased him, asking if a man of his stature was really going to stay home because of a woman’s bad dream.

Peer pressure is a hell of a thing.

So, Caesar walks out. On the way to the Senate, he supposedly ran into the seer Spurinna, who had previously warned him to "beware the Ides of March." Caesar laughed and told him the Ides had come. Spurinna’s comeback was legendary: "Aye, Caesar, but not gone."

The Senate wasn't even meeting in the actual Senate House that day. It was under renovation. They were meeting in a side hall of the Theatre of Pompey. This is one of those tiny details that clarifies Julius Caesar: how he died; he died at the feet of a statue of his greatest rival, Pompey the Great. The irony is so thick you could cut it with a... well, you get it.

The Attack: It Wasn't a Clean Kill

When he finally sat down, the conspirators gathered around him under the guise of presenting a petition. Tillius Cimber grabbed Caesar’s toga, pulling it down from his neck. This was the signal.

"Is this violence?" Caesar supposedly shouted.

Then came the first strike. Casca, who was standing behind him, lunged with a dagger. But here’s the thing: Casca was nervous. He missed Caesar’s throat and hit him in the shoulder or chest instead. It was a glancing blow. Caesar actually fought back, grabbing Casca’s arm and stabbing it with his stylus—the metal pen he used for writing. For a few seconds, it wasn't an assassination; it was a wrestling match.

But then the rest of the mob closed in.

There were about 60 conspirators in total, though only about 23 actually landed a blow. Because they were all crowding around him, trying to get their "honor" in by stabbing the dictator, they actually ended up stabbing each other. Cassius supposedly sliced Brutus’s hand by mistake. It was total, unmitigated chaos.

The Myth of "Et Tu, Brute?"

We have to talk about the famous line. "Et tu, Brute?" (And you, Brutus?).

Most historians, including Suetonius and Plutarch, think he probably said nothing at all. If he did say something, it was likely in Greek, not Latin. The phrase "Kai su, teknon?" translates to "You too, child?" or "You too, my son?" This has led to centuries of gossip about whether Marcus Brutus was actually Caesar’s illegitimate son.

📖 Related: Video of Trump and Microphone: What Really Happened at Joint Base Andrews

While Caesar had a long-term affair with Brutus’s mother, Servilia, the math doesn't quite check out for him to be the father. Still, the betrayal stung. When Caesar saw Brutus among the attackers, he allegedly stopped fighting, pulled his toga over his head, and just let it happen. He gave up.

The Forensic Reality of 23 Stabs

In 44 BCE, a doctor named Antistius performed what is arguably the first recorded autopsy in history. He examined the body and concluded that out of the 23 wounds, only one was actually fatal. It was the second wound, the one in the chest that pierced the heart.

Caesar didn't die instantly. He bled out on the floor of a theater while the senators who weren't in on the plot ran for their lives. The conspirators thought they would be cheered as liberators. They weren't. The city went into a state of shocked silence.

The assassins ended up locking themselves on the Capitoline Hill because the Roman public wasn't throwing them a parade; they were terrified and angry.

Why the Assassination Failed its Own Goal

The conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius, wanted to "save the Republic." They thought that by killing the "tyrant," the old ways of the Senate would just magically snap back into place.

They were wrong. So wrong.

Basically, they killed the man but preserved the office. Caesar’s death created a power vacuum that led to a series of civil wars. Instead of returning to a Republic, Rome ended up with an even more powerful Emperor: Augustus.

If you look at the timeline, Julius Caesar: how he died is actually the starting point for the Roman Empire. The assassins didn't realize that the people of Rome actually liked Caesar. He gave them grain. He gave them land. He gave them "bread and circuses." When Mark Antony read Caesar’s will aloud in the Forum and revealed that Caesar had left money to every single Roman citizen, the mood turned from confusion to a murderous riot.

Common Misconceptions About the Death of Caesar

People get a lot of this stuff mixed up. For starters, he wasn't killed in the Capitol. He was killed in a theater complex.

- The "Et Tu" Quote: Shakespeare wrote that, not Caesar.

- The Number of Stabs: It wasn't hundreds. It was 23.

- The Location: The Curia of Pompey, not the Roman Forum.

- The Motive: It wasn't just "freedom." Many of these guys were just pissed that Caesar was ignoring their traditional privileges or had passed them over for promotions.

It’s also worth noting that Caesar had been warned. Multiple times. Not just by the seer, but by his own doctors and friends who noticed he was having "falling sickness" episodes—likely epilepsy or mini-strokes. Some historians even wonder if Caesar let it happen because his health was failing and he wanted to go out at the height of his power rather than wither away.

👉 See also: News Albany Park Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About the Neighborhood Right Now

A Legacy Written in Blood

You can't talk about how Caesar died without looking at the immediate aftermath. The body was eventually cremated in the Forum. The spot is still there today; people still leave flowers on the altar of the Temple of Caesar.

It’s kind of wild when you think about it. One of the most powerful men to ever live was ended by a group of his "friends" with cheap daggers in a side room of a theater. No grand battle. No heroic last stand. Just a messy, panicked struggle in the dirt.

The autopsy by Antistius provides a fascinating look at the medical side of history. It proves that even with dozens of attackers, most of them were too scared or too incompetent to land a killing blow. They were amateurs at murder, even if they were pros at politics.

Practical Takeaways from Caesar's Final Moments

While most of us aren't worried about Roman senators hiding daggers in their togas, the story of Julius Caesar: how he died offers some pretty blunt lessons for anyone in leadership or history buffs alike.

- Understand Your Security: Caesar’s decision to dismiss his bodyguards was an act of ego that cost him his life.

- Read the Room: The conspirators completely misjudged the public's loyalty to Caesar. They focused on the "idea" of the Republic while the people cared about the "reality" of their dinner.

- Betrayal is Usually Close to Home: The people who killed Caesar weren't his enemies from the battlefield; they were the people he had pardoned and promoted.

- Forensics Matter: The fact that we have an autopsy report from over 2,000 years ago shows that even the ancients understood the importance of documenting the "how" and "why" of a crime.

To dive deeper into the world of Roman politics, you should look into the Life of Caesar by Plutarch or Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars. These primary sources provide the raw, often gossipy details that modern textbooks tend to sanitize. For a more modern perspective on the medical findings, the work of Dr. Francesco Galassi, a paleopathologist who has studied Caesar’s health, is incredibly insightful.

The Ides of March isn't just a date on a calendar; it's a reminder that even the most powerful people are vulnerable to the chaos of a few determined—if uncoordinated—individuals. If you're ever in Rome, skip the Colosseum for a second and go to the Largo di Torre Argentina. That's where the Theatre of Pompey stood. You can see the ruins where the Republic died and the Empire was born.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

- Visit the Largo di Torre Argentina in Rome to see the actual site of the assassination.

- Read the primary accounts of Suetonius to see the "tabloid" version of Roman history.

- Map out the civil war that followed between Octavian and Mark Antony to understand how Caesar’s death changed the world.