You’ve probably heard of Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley. They’re the survivors. But if you went back to the 1980s, Kidder Peabody and Co was the name that carried a specific kind of old-school, blue-blooded weight. It was a firm that started in 1865, survived the Civil War, outlasted the Great Depression, and then—honestly—just got weirdly, tragically messy.

By the time the mid-90s rolled around, this 130-year-old titan didn't just stumble; it basically vaporized. Most people remember it for one guy, Joseph Jett, and a bond-trading scandal that sounds like a movie script. But the truth is more complicated than a single "rogue trader" narrative. It’s a story about what happens when a massive industrial conglomerate like General Electric tries to run a Wall Street house like a lightbulb factory.

The Boston Brahmin Roots

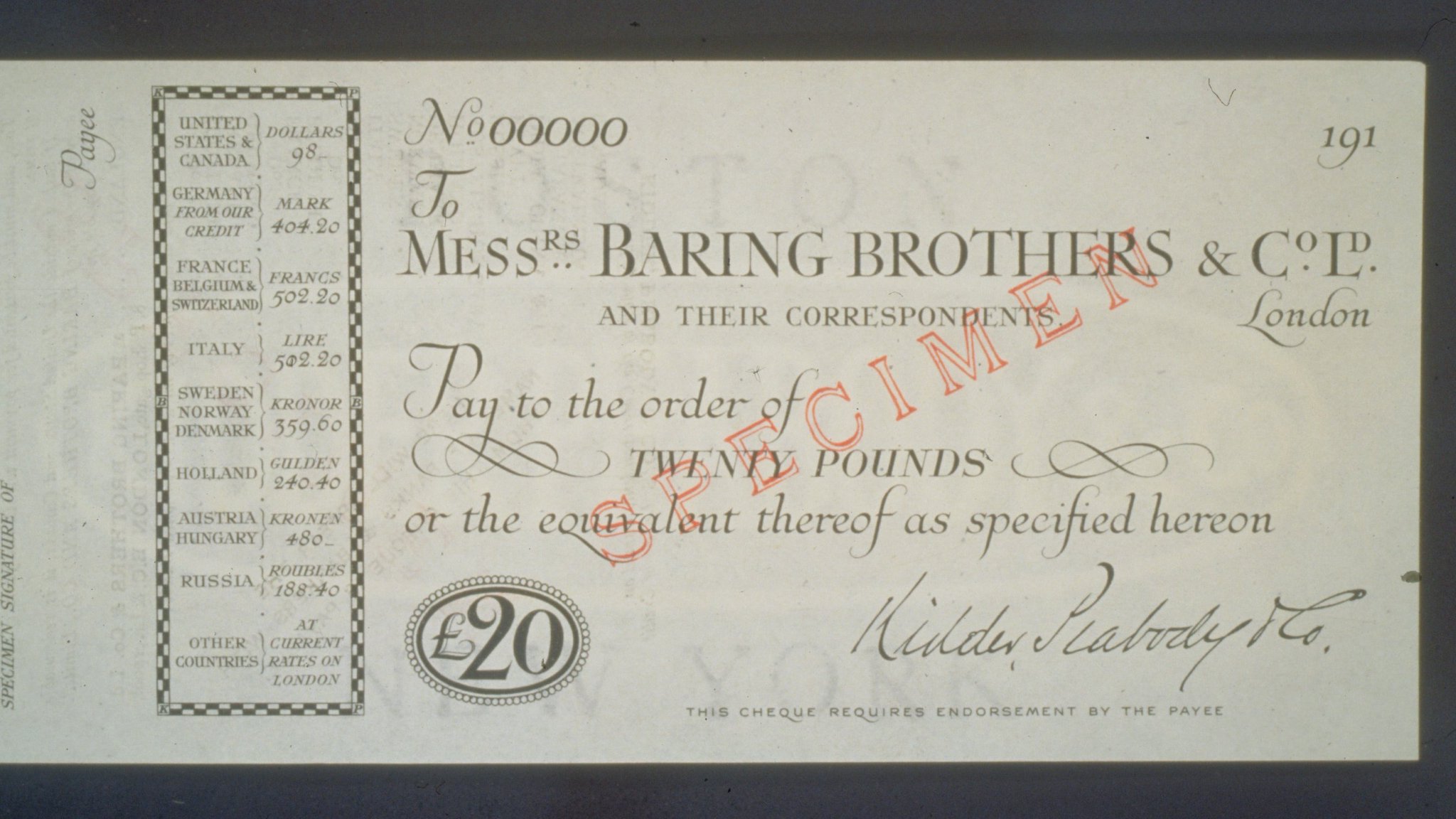

Back in the day, Kidder Peabody and Co was the "white shoe" firm of Boston. Henry Kidder and the Peabody brothers (Francis and Oliver) weren't looking to "disrupt" anything. They were clerks who took over a business from their retiring boss. For decades, they were the "money trust." They were so big that by 1912, a Congressional committee (the Pujo Committee) basically accused them of helping run a secret monopoly over American credit alongside J.P. Morgan.

🔗 Read more: 1 UAE Dinar to USD: What Most People Get Wrong

That’s power. Real, quiet, wood-paneled office power.

But the 1929 crash almost killed them. They were rescued by Albert Gordon, a man who basically rebuilt the firm's soul over sixty years. He focused on utility bonds and niche municipal markets. It was stable. It was profitable. It was boring.

Then came 1986.

When Jack Welch Bought a Bank

General Electric, led by the legendary (and controversial) Jack Welch, decided they wanted in on the Wall Street gold rush. They bought 80% of Kidder Peabody and Co for $602 million. At the time, it seemed like a genius move. GE was a manufacturing beast, and adding a high-octane investment bank to its GE Capital arm felt like a shortcut to infinite growth.

Welch eventually found out that bankers and engineers don’t mix.

Almost immediately, the "skunk in the place" emerged. Only months after the GE deal, the firm got hit by an insider trading scandal involving Martin Siegel. Kidder had to pay $25 million to the SEC to settle things. Welch was famously furious. He told employees he never would have touched the firm with a "10-foot pole" if he knew what was going on.

📖 Related: Tax Filing Services Online: Why Most People Are Still Overpaying

But the worst was yet to come.

The Joseph Jett "Phantom" Profits

If you want to understand why Kidder Peabody and Co doesn't exist anymore, you have to talk about Joseph Jett. In 1991, they hired Jett to trade government bonds. He had an MIT degree and a Harvard MBA. He was brilliant, or at least he appeared to be.

Within two years, Jett was the firm’s "Man of the Year." He was bringing in hundreds of millions in profits—or so the computer said. In 1993 alone, he was awarded a $9 million bonus. His boss, Ed Cerullo, took home $20 million.

The problem? The profits didn't exist.

Jett had discovered a glitch in Kidder’s internal accounting software. The system basically couldn't handle the way he was recording "forward" trades on zero-coupon bonds (STRIPS). Every time he entered a trade to be settled in the future, the computer booked an immediate "profit" that wasn't real. To keep the scam going, he had to keep making bigger and bigger trades to cover the old ones.

🔗 Read more: Earnings Big Tech Today: Why the AI Spending Spree Is Finally Getting a Reality Check

It was a pyramid scheme hidden in a ledger.

The $350 Million Hole

By April 1994, the music stopped. GE's auditors finally looked under the hood and found a $350 million hole in the books. Jett was fired instantly. The firm’s reputation was shredded. GE, which prided itself on "Six Sigma" precision and perfect accounting, looked like a bunch of amateurs who had been taken for a ride by a single guy with a clever spreadsheet trick.

Honestly, the fallout was brutal. GE didn't just fire Jett; they cleaned house. They ousted the CEO, Michael Carpenter, and replaced him with GE loyalists. But the damage was done. Wall Street is built on trust, and nobody trusted Kidder anymore.

The Fire Sale to PaineWebber

GE wanted out. Fast.

In late 1994, they sold the remains of Kidder Peabody and Co to PaineWebber for about $670 million in stock. It was a "hurried" sale, basically a salvage operation. PaineWebber didn't want the brand; they wanted the brokers and the assets.

The Kidder Peabody name, which had survived through thirteen decades of American history, was simply dropped. It was gone. Just like that.

Why It Still Matters Today

The ghost of Kidder Peabody and Co still haunts modern finance for a few reasons.

- Incentive Structures: Jett's bosses were so blinded by the massive bonuses they were getting from his "profits" that they ignored every red flag.

- The "Financialization" Warning: This was the first big sign that industrial companies (like GE) shouldn't necessarily be running shadow banks. It took another 20 years for GE to finally realize this and dismantle GE Capital.

- Software is Not Truth: The Jett scandal proved that if your accounting software is flawed, a smart person will find the crack and drive a truck through it.

Actionable Insights for Investors

- Watch the "Outliers": If one trader or one department is making 10x what everyone else is, and nobody can explain how in simple English, be terrified.

- Corporate Culture Clashes: When a company in one industry (Tech/Retail) buys a company in a completely different world (Finance/Pharma), the integration usually fails. Cultural friction kills more mergers than bad math does.

- Verify the "Strips": In modern trading, always look for the settlement dates. Unrealized gains are just numbers on a screen until the cash actually moves.

Kidder Peabody and Co wasn't just a victim of one "rogue" guy. It was a victim of its own desire to be bigger than its systems allowed. It serves as a permanent reminder that on Wall Street, if something looks too good to be true, it’s probably a glitch in the software.

To truly understand the risks in your own portfolio, start by auditing the "star performers" in your holdings. Look for transparency in their reporting. If a company's earnings are consistently driven by one opaque division, it's time to dig into their 10-K filings for any mention of "internal control weaknesses."