You’ve seen the diagram a thousand times. A block attached to a coil, sliding back and forth on a frictionless surface. It’s the bread and butter of high school physics. But honestly, the way we talk about kinetic energy in a spring is a bit of a lie. We treat the spring like it's a ghost—massless, perfect, and existing only to provide a force. In the real world, springs have weight. They have inertia. If you’ve ever watched a heavy industrial spring uncoil, you know it’s not just the "load" doing the moving. The spring itself is carrying a significant amount of the system's energy.

Energy is messy.

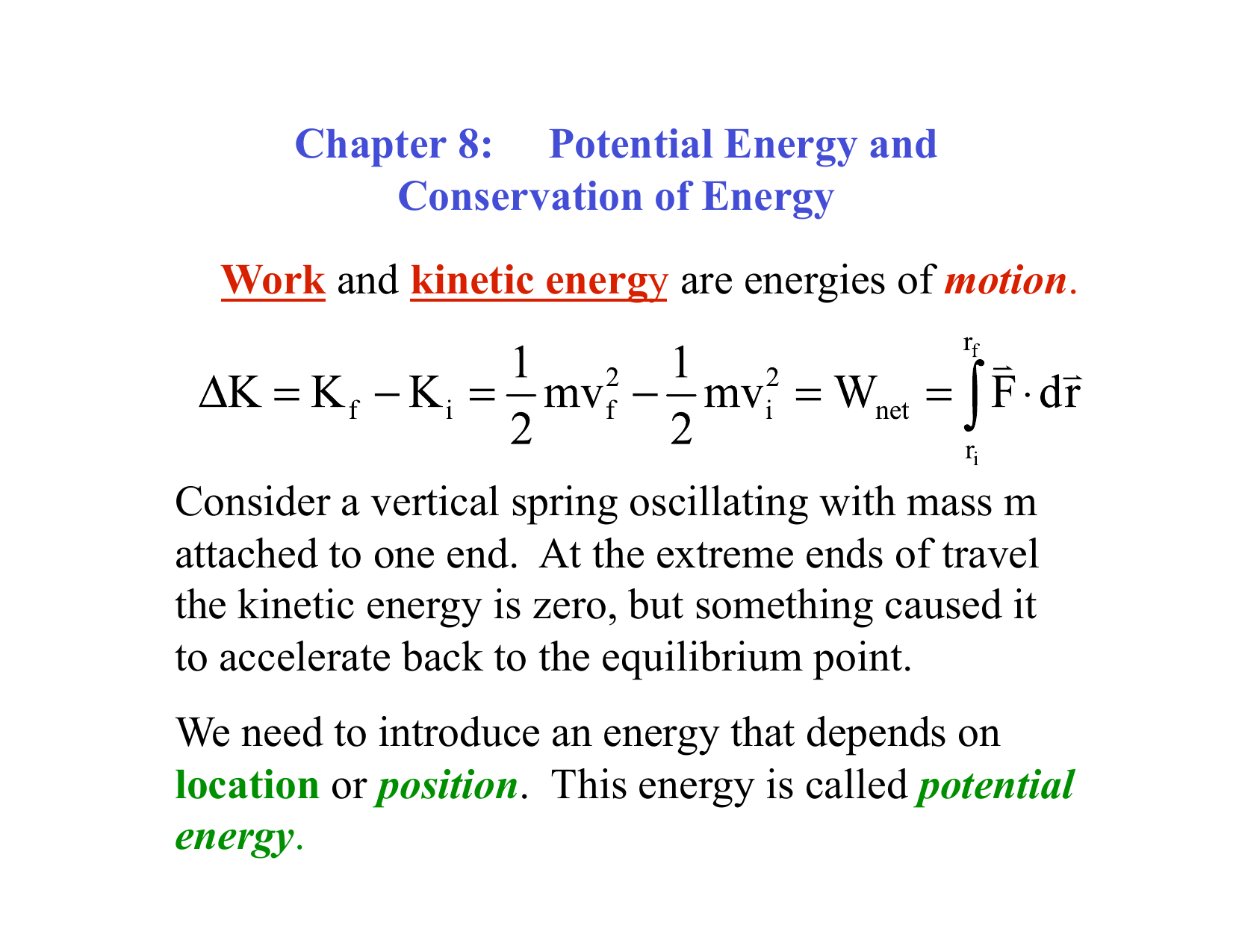

Most people think of kinetic energy as a simple $K = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$ equation. When we apply that to a spring system, we usually focus entirely on the object attached to the end of it. We calculate the potential energy stored in the coils ($U = \frac{1}{2}kx^2$) and assume it all converts into the velocity of the block. But physics isn't always that tidy. If you’re designing a high-performance suspension system or a precision mechanical watch, ignoring the internal mass of the spring will lead to math that just doesn't work in the shop.

The Reality of Kinetic Energy in a Spring Systems

When a spring stretches or compresses, every single coil moves. However, they don't move at the same speed. The coil attached to the wall is stationary. The coil attached to the weight is moving at the maximum velocity ($v$). Everything in between is moving at some gradient of that speed. This means the kinetic energy in a spring isn't just about the "m" of the block, but also a fraction of the "m" of the spring itself.

💡 You might also like: Elon Musk Saves Astronauts: What Really Happened with the Boeing Starliner Rescue

Lord Rayleigh, a giant in the world of acoustics and vibrations, figured this out way back in the late 19th century. He realized that to get an accurate frequency for a vibrating spring, you have to add about one-third of the spring's mass to the mass of the load. It's a correction factor that bridges the gap between the "ideal" world of textbooks and the "real" world of engineering. If you don't account for this, your calculations for kinetic energy will be off by a margin that can actually cause mechanical failure in high-frequency applications.

Why Mass Distribution Changes Everything

Imagine a Slinky. If you hold one end and let the other drop, it doesn't just fall like a rock. It collapses on itself. This happens because the tension and the mass are distributed throughout the entire body of the spring. In a standard oscillating system, the kinetic energy is constantly being swapped back and forth with potential energy.

At the "equilibrium point"—the spot where the spring is neither stretched nor compressed—the potential energy is zero. All of it has turned into kinetic energy. But here’s the kicker: if the spring is heavy, a huge chunk of that energy is living inside the steel of the coils, not in the object it's pushing. This is why heavy springs feel "sluggish." They have high inertia. They're literally fighting their own weight to move.

Real-World Engineering: Where the Math Hits the Metal

Let's look at a valvetrain in an internal combustion engine. These springs are opening and closing valves thousands of times per minute. At 8,000 RPM, the kinetic energy in a spring becomes a massive liability. If the spring has too much mass, it can't move fast enough to close the valve before the piston comes back up. This is called "valve float," and it's a great way to turn an expensive engine into a pile of scrap metal.

Engineers solve this by using "beehive" springs. They make the top of the spring narrower than the bottom. Why? To reduce the mass at the moving end. By reducing the mass that has the highest velocity, they lower the total kinetic energy the system has to manage. It's a brilliant bit of geometry that allows engines to rev higher without needing stiffer, heavier springs that would just eat up more power.

💡 You might also like: Is Sound Potential or Kinetic Energy? The Answer is More Dynamic Than You Think

The Calculus of the "Effective Mass"

If you’re the type who likes to see the "why," the one-third rule comes from integrating the kinetic energy of infinitesimal segments of the spring.

Suppose you have a spring of length $L$ and total mass $M_s$. If the end of the spring is moving at velocity $v$, a segment at distance $x$ from the fixed end is moving at $v(x) = v \cdot (\frac{x}{L})$. To find the total kinetic energy, you integrate the kinetic energy of each tiny piece:

$$K_{spring} = \int_0^L \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{M_s}{L} dx\right) \left(\frac{v \cdot x}{L}\right)^2$$

When you run those numbers, you get:

$$K_{spring} = \frac{1}{6} M_s v^2$$

Compare that to the standard $K = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$. You’ll notice that $\frac{1}{6}$ is exactly one-third of $\frac{1}{2}$. That’s why we say the "effective mass" of the spring is $M/3$. It’s a beautiful bit of math that shows up in everything from seismographs to the scales at your local grocery store.

Misconceptions That Cause Problems

One of the biggest mistakes people make is assuming that "stiffer is always better" for returning energy.

Actually, stiffness (the $k$ constant) and mass are in a constant tug-of-war. A very stiff spring might store more potential energy, but if it requires a massive amount of material to achieve that stiffness, the kinetic energy in a spring during release might be so high that the system becomes inefficient. You end up wasting energy just moving the spring itself. This is why materials science is so obsessed with titanium springs in racing—they give you the stiffness without the "penalty" of high kinetic energy.

Another weird thing? Temperature.

Most people think of temperature affecting the length of a metal, which it does. But heat also changes the shear modulus of the material. A hot spring is "softer." This changes how energy is stored and released. In precision aerospace components, a few degrees of temperature change can shift the resonant frequency of a spring system enough to cause "resonance disaster," where the kinetic energy builds up until the part literally shakes itself to pieces.

Actionable Insights for Using Spring Physics

If you are working on a project that involves moving parts and springs—whether it's a DIY 3D printer, a mountain bike suspension, or a hobbyist robot—keep these practical points in mind:

✨ Don't miss: Apple Store Miami Beach: Why This Lincoln Road Landmark Still Hits Different

- Don't ignore the spring's own weight. If your load (the object being moved) is less than 10 times the weight of the spring, your "basic" physics formulas will be wrong. Use the $M/3$ rule to get closer to reality.

- Watch for Surge. In fast-moving systems, waves of kinetic energy travel through the spring like a pulse. This is called "spring surge." It can cause the coils to crash into each other (coil bind) even if you haven't fully compressed the spring.

- Material matters more than size. If you need high speed, go for materials with a high strength-to-weight ratio. Chrome silicon or titanium alloys are the gold standards because they minimize the "parasitic" kinetic energy of the spring's mass.

- Check your damping. Because a real spring has mass and kinetic energy, it won't stop moving the instant you want it to. You need a way to dissipate that energy, usually through friction or hydraulic damping (like the shocks on your car).

Understanding the kinetic energy in a spring is really about moving past the "ideal" and embracing the friction, mass, and mess of the physical world. It’s the difference between a calculation that looks good on paper and a machine that actually works when you flip the switch. Stop treating the spring as a middleman. Start treating it as a moving part. That's how you master the physics of motion.