Ever looked at a map and felt completely lied to? Thomas Jefferson did. In 1803, the United States was basically a giant blank space once you crossed the Mississippi. The maps Jefferson handed to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were filled with "wishful thinking" geography. They expected a flat, easy stroll to the Pacific. They thought the Rocky Mountains were just a single, tiny ridge. They were dead wrong.

Honestly, the story of lewis and clark maps isn't just about drawing lines. It is about a massive psychological shift for a young nation. Before the Corps of Discovery set foot in the mud, people truly believed there was a "Northwest Passage"—a magical water highway connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific. Clark’s final 1814 map didn't just show where the rivers were; it killed a centuries-old dream of an easy route to Asia. It proved the West was huge, rugged, and dangerous.

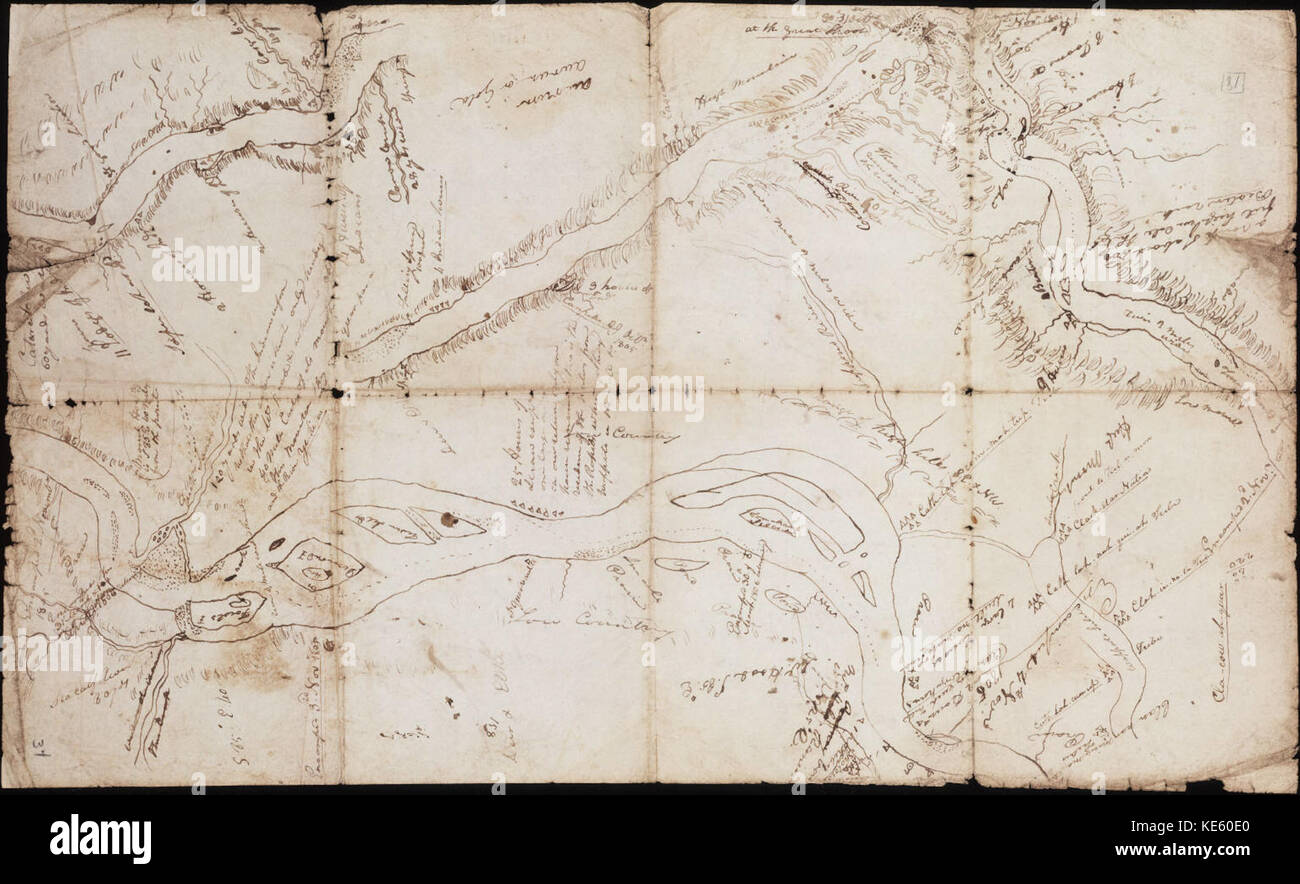

The "Blank Map" That Started It All

Before the duo left, they weren't starting from scratch. They had the Nicholas King map of 1803. It was basically a compilation of the best guesses of the time.

It’s kinda wild to look at now. Huge swaths of the continent were just empty white paper. King used data from British explorers and traders, but much of it was hearsay. For instance, they had no clue how wide the Rockies actually were. Jefferson's instructions to Lewis were pretty intense: map every twist, turn, and rapid. He wanted to know where the country ended.

To do this, they carried about 15 pounds of books and a chest full of brass instruments. We're talking sextants, octants, and a chronometer that cost about $250—a fortune back then. If that chronometer stopped ticking, their longitude calculations went out the window.

How William Clark Actually Made the Maps

William Clark was the primary "map guy." While Lewis was busy identifying new plants and keeping a grizzly bear from eating everyone, Clark was obsessively counting paces and checking his compass.

🔗 Read more: Ocean Definition: Why Most People Actually Get This Wrong

They used a technique called "dead reckoning." Basically, you estimate your position based on how fast you’ve traveled from a known point. It’s remarkably imprecise by modern standards. But Clark was a natural. He’d stand on the deck of a keelboat, squinting at the shore, estimating distances in poles and miles.

The Secret Weapon: Indigenous Knowledge

Here is the thing most history books gloss over: the lewis and clark maps wouldn't exist without Native Americans. Seriously. When the Corps got stuck or lost, they didn't just stare at their brass sextants. They asked the people who actually lived there.

- The Mandan and Hidatsa: During the winter of 1804, tribal leaders drew maps in the dirt and on hides for the explorers. They described the Great Falls of the Missouri long before the white men saw them.

- Sacagawea: While she wasn't a "guide" in the sense of leading every step, her geographical memory was vital. She recognized landmarks like Beaverhead Rock, which told the captains they were in Shoshone territory.

- The Shoshone and Nez Perce: These groups provided the specific Intel needed to cross the Bitterroot Mountains. Without their "dirt maps," the expedition likely would have starved in the snow.

The 1814 Map: A Masterpiece of Error and Accuracy

When the journals were finally published in 1814, they included a massive map titled A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track. This is the "big one." It was the first time the American public saw the West as a real, physical place rather than a myth.

💡 You might also like: Western US Maps Highways: Why Your GPS Might Actually Be Wrong

But it wasn't perfect.

Clark's estimations of the Yellowstone River were off by hundreds of miles. He thought it was a "navigable superhighway." In reality, it was full of obstructions. He also completely missed the Great Salt Lake. You’d think a giant inland sea would be hard to miss, but they just didn't go that way.

Yet, for all its flaws, this map was the gold standard until the 1840s. It gave the U.S. a "claim" to the Oregon Territory. It was a political tool as much as a navigational one.

Why We Still Care About These Maps Today

You might think lewis and clark maps are just dusty relics in the Library of Congress. You’d be wrong. They are used today by ecologists to see how rivers have shifted over 200 years.

By comparing Clark’s sketches of the Missouri River to modern satellite imagery, scientists can track "meander scars"—the places where the river used to flow before we dammed it up. It’s a literal time machine for the American landscape.

Also, if you're a hiker, you've probably stood exactly where Clark stood to take a "bearing." The National Park Service maintains the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which spans thousands of miles. You can literally follow their map from Pittsburgh to the Pacific.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this cartographic rabbit hole, don't just read a summary. Do this:

- Visit the Digital Archives: The Library of Congress has high-resolution scans of the 1814 map. Zoom in on the "Stony Mountains." You’ll see the exact moment the "Northwest Passage" myth died.

- Check Out "Discovering Lewis & Clark": This website is a goldmine. It breaks down the specific surveying instruments they used, like the circumferentor.

- Compare the 1803 King Map to the 1814 Clark Map: Look at the area around the Missouri headwaters. The difference represents three years of brutal, life-changing exploration.

- Visit Pompeys Pillar: In Montana, you can see the only physical mark left by the expedition on the trail—Clark’s signature carved into a rock. He mapped this exact spot.

The lewis and clark maps were never just about geography. They were about the end of an old world and the messy, complicated birth of a new one. They remind us that even the best "experts" can be totally wrong until they actually get out there and walk the ground.