You’ve probably seen the black-and-white clips or the vintage posters. A red-headed family huddled around a stern-looking man in a high collar. It looks like a greeting card from a time that never actually existed. But here is the thing: Life With Father isn't just some dusty piece of 1940s nostalgia.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle it exists at all. Clarence Day Jr., the man who wrote the original essays, was basically an invalid for most of his adult life. He suffered from crippling arthritis that left him confined to a chair, yet he spent his days looking back at his childhood with a sharp, satirical, and surprisingly warm lens.

👉 See also: The Truth About Ophelia Lyrics: What The Lumineers Actually Meant

When people talk about the "classic American family," they often point to this story. But if you actually look at the details, it’s a lot messier—and funnier—than the sanitized version in our heads.

The Man Behind the Bellow

Clarence Day Sr. was a powerhouse. He wasn't just a character; he was a real-life Wall Street broker who viewed his home like a business. If the coffee was cold or the mail was late, it wasn't a minor inconvenience. It was a personal affront to the natural order of the universe.

He groaned. He shouted. He stomped.

Yet, the magic of the writing—and later the play and film—is that we don't hate him. We’ve all known a "Clare." He’s that person who is convinced that if everyone just followed his very specific, very loud instructions, the world would finally stop being so incompetent.

Why the baptism plot actually matters

The core of the famous 1947 movie (and the record-breaking Broadway play) is Vinnie’s quest to get Clare baptized. It sounds like a quaint, dated religious trope, doesn't it?

It’s actually a power struggle.

Vinnie, played by the legendary Irene Dunne in the film, is the only person who can truly handle Father. She doesn't use logic because logic doesn't work on a man who thinks he invented it. Instead, she uses a sort of chaotic, circular reasoning that leaves him completely baffled.

When she finds out he was never baptized, she panics. Not just because of the theology, but because she can't imagine a heaven where he isn't there to complain about the management.

- The Stakes: If he isn't baptized, they aren't "legally" married in her eyes.

- The Strategy: She uses his own stubbornness against him.

- The Result: One of the most famous comedic standoffs in American theater history.

Breaking Broadway Records

Before it was a movie starring William Powell and a young Elizabeth Taylor, it was a stage phenomenon. Life With Father opened on Broadway in 1939 and didn't close until 1947.

That is 3,224 performances.

To put that in perspective, it remains the longest-running non-musical play in Broadway history. People in the late 30s and early 40s were desperate for this. The world was falling apart, and here was a story about a family where the biggest problem was a misplaced ledger or a new suit for the oldest son.

💡 You might also like: Who Played Rosetta Tinker Bell: Why the Garden Fairy Swapped Voices

It provided a "wholesomeness" that felt like a shield against the news coming out of Europe.

The transition to the screen

When Warner Bros. took it on, they didn't mess around. They spent a fortune. They used Technicolor when it was still a massive, expensive undertaking. They even had to deal with the "red hair" problem.

In real life, all the Day boys were redheads. To make this work on screen, the actors had to have their hair dyed constantly. It was a grueling process, but it created that iconic, vibrant look that defines the movie today.

Is it still "Good"?

This is where things get tricky. If you watch it today, some parts feel... uncomfortable.

Father is essentially a domestic tyrant. He treats the string of maids like disposable machinery. He views Vinnie’s lack of "business sense" with a patronizing smirk. For a modern audience, the power imbalance can feel less like a "gentle comedy" and more like a documentary on why the feminist movement had to happen.

But Clarence Day Jr. knew what he was doing.

He wasn't writing a manual on how to run a home. He was writing about a specific, vanishing breed of Victorian man. He was poking fun at his father’s "serene self-assurance."

If you read the original essays in The New Yorker, the satire is much sharper. The play and the movie sanded down the edges to make it more "heartwarming," but the bones of the story are still about the absurdity of a man trying to control a world that is inherently uncontrollable.

The "Day" Legacy in Pop Culture

You can see the DNA of Life With Father in almost every family sitcom that followed.

The blustering father who thinks he’s in charge but is actually being managed by his wife? That’s the blueprint for I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, and even The Simpsons.

Clare Day Sr. is the original "grumpy dad with a heart of gold."

Actionable Insights for Fans and Newcomers

If you want to actually dive into this world without getting lost in the "old-fashioned" tropes, here is how to do it:

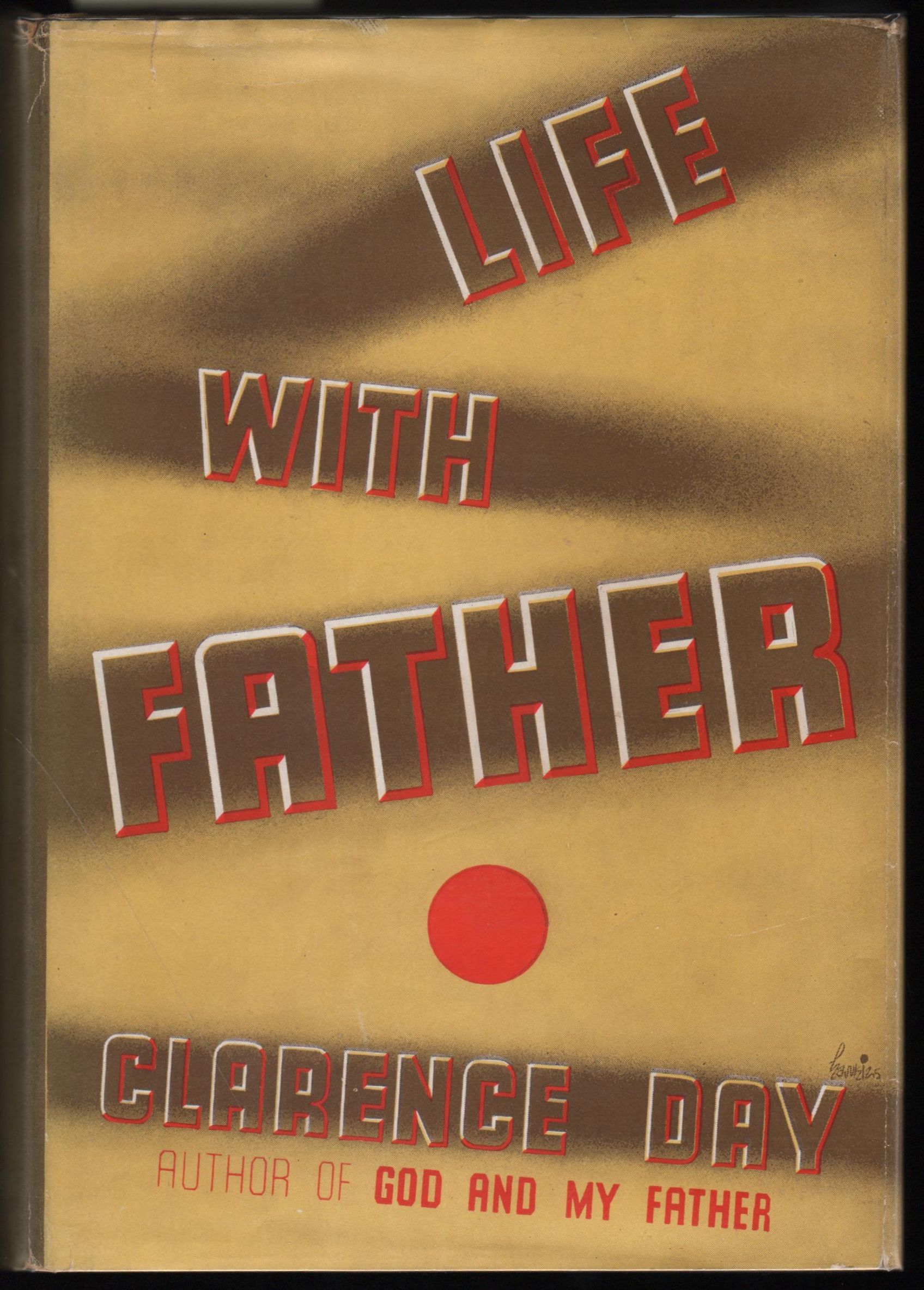

- Read the essays first. Don't start with the movie. Find a copy of Clarence Day’s God and My Father or the titular Life With Father. The prose is lean, witty, and surprisingly modern in its cynicism.

- Watch for the "Vinnie" moves. When watching the film, pay attention to Irene Dunne. She isn't a submissive housewife; she is a tactical genius. Her ability to navigate Clare’s temper is a masterclass in psychological warfare.

- Context is everything. Remember that this was written by a man who was almost completely paralyzed by illness. The "energy" and "noise" he describes in the Day household wasn't just a memory; it was a lost world he was trying to reclaim through his pen.

The story of the Day family isn't just about a baptism or a brokerage firm. It’s about the friction of people living together—the loud, messy, frustrating, and ultimately loving collision of personalities that happens in every house, regardless of the century.

Next Step: To see the sharpest version of this story, look for the 1935 first edition of the essays. The original drawings by Clarence Day himself add a layer of whimsy and "bite" that the Technicolor movie often misses.