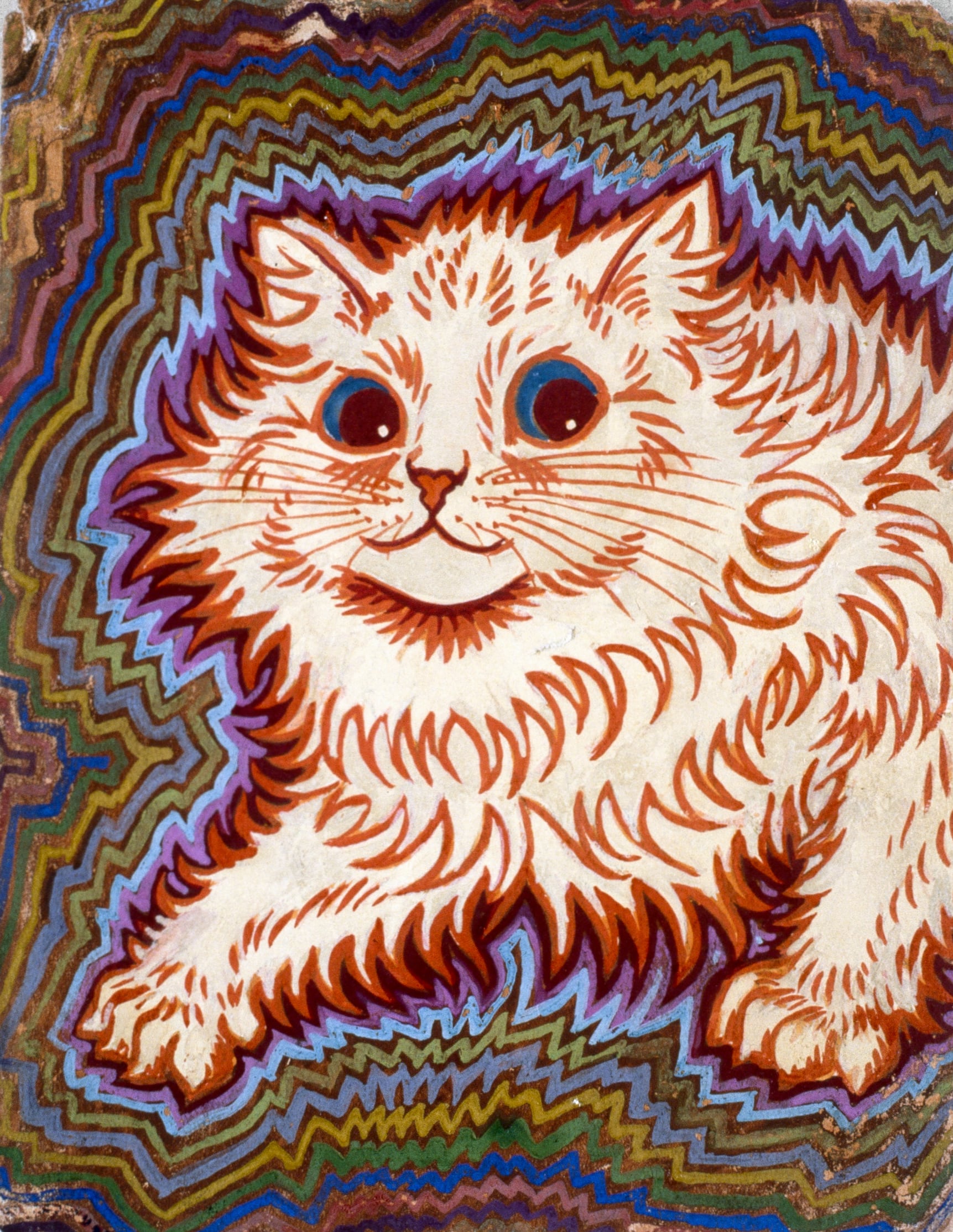

Walk into any psychology 101 lecture and you’ll probably see them. Those eight cat drawings. They start as cute, wide-eyed kittens and slowly—frame by frame—dissolve into jagged, neon geometric explosions. The "Kaleidoscope Cats." For decades, teachers used them as the ultimate visual proof of a mind fracturing under schizophrenia. It’s a clean narrative. It makes sense. It’s also basically a lie.

The search for the louis wain final drawing usually leads people down this rabbit hole of "psychotic deterioration." But if you want to know what the man actually drew before he died in 1939, you have to look past the textbook myths. The reality is way more interesting—and honestly, a lot more human—than a simple descent into madness.

The Myth of the Kaleidoscope Progression

Let’s get the big one out of the way first. Those famous "psychedelic" cats weren't found in a dated sketchbook. They were found in a junk shop years later by a psychiatrist named Walter Maclay. He was the one who decided they looked like a timeline of a "broken" mind.

Wain never dated them.

In fact, while he was supposedly "lost" in these abstract patterns, he was still drawing perfectly normal, cute cats for nurses and visitors. He didn't lose the ability to draw a cat; he just became obsessed with patterns. He called them "wallpaper patterns." Think about it—his dad was a textile trader. His mom designed church embroideries. The man had intricate fractals in his DNA long before he ever went to an asylum.

So, What Was the Actual Louis Wain Final Drawing?

If we’re being technical, there isn't one single "Final Canvas" that everyone agrees on. Because Wain was a prolific sketcher until the very end, his final works are scattered across hospital archives and private collections. However, his output at Napsbury Hospital—where he spent his last nine years—gives us the clearest picture of his final state of mind.

His late-stage work wasn't just "crazy" geometry. It was a mix of three distinct styles:

- The Landscape Cats: He started painting incredibly detailed, lush garden scenes. These weren't scary. They were peaceful. He’d spend hours in the Napsbury gardens, sketching the cats that lived there.

- The Mirror Cats: These were symmetrical, highly colored portraits that looked like stained glass. They were complex, sure, but they weren't "disorganized." They were meticulously planned.

- The "I Am Happy" Cat: This is the one that breaks most people’s hearts. One of his last well-known sketches features a cat with a wide, genuine smile and a caption that essentially says, "I am happy because everyone loves me."

That doesn't sound like a man who had "lost his mind." It sounds like a man who finally found peace after a life of poverty and grief.

📖 Related: Farewell Uncle Tom Movie: Why This 1971 Film is Still So Explosive

The Electrical Life at Napsbury

By the time he got to Napsbury in 1930, Wain was a celebrity again. H.G. Wells and even the Prime Minister had intervened to get him out of the "pauper" wards of Springfield and into a place with a garden.

He became obsessed with the idea of "electricity." He thought everything was vibrating with energy. You can see it in the louis wain final drawing styles—those jagged, spiky lines aren't just random "schizophrenic" marks. They were his attempt to draw the literal energy he felt coming off the cats. He wasn't drawing a distorted cat; he was trying to draw a cat plus the aura he believed surrounded it.

Why the "Final Drawing" Matters Today

We love the "tortured artist" trope. We want to believe that mental illness creates some kind of magical, trippy portal into another dimension. But the truth about Louis Wain’s final years is that he remained a craftsman.

👉 See also: Dandadan Episode 9 Watch: Why the Acrobatic Silky Arc is Peak Shonen

Experts like Dr. Michael Fitzgerald have even questioned the schizophrenia diagnosis entirely, suggesting Wain might have been on the autism spectrum. His "deterioration" wasn't a loss of skill—it was a deep-dive into his own specific interests: symmetry, color, and textiles.

If you look at the cats he drew in 1938 and 1939, they aren't "broken." They are vibrant. They are loud. They are the work of a man who stopped caring about what the London art editors wanted and started drawing exactly what he saw in his head.

Actionable Insights: How to View Wain’s Art

If you’re looking at these drawings and trying to understand the man, keep these things in mind:

- Ignore the textbooks: If you see the eight cats arranged in a "descent into madness" line, remember that a doctor made that up for a lecture. It’s not a timeline.

- Look for the textiles: Notice the backgrounds. The patterns in his "psychedelic" cats often mimic the Victorian lace and carpets he grew up with.

- Check the dates (or lack thereof): Most of the truly abstract stuff is undated. Don't assume "more abstract" means "closer to death."

- Visit the source: If you really want to see the "final" feel of his work, the Bethlem Museum of the Mind holds the most authentic collection of his hospital-era drawings.

The louis wain final drawing isn't a tragedy. It’s a testament to a guy who, despite everything the world threw at him, never stopped trying to capture the secret, electric life of cats. He didn't fade away into a "kaleidoscope mess." He just turned up the brightness until the rest of us couldn't keep up.