It starts with a scent. Not the sweet, heavy perfume of a jazz club or the smell of rain on a New York sidewalk, but something metallic and rotting. When Billie Holiday stood at the microphone at Café Society in 1939, she wasn't just singing a jazz standard. She was throwing a grenade. The lyrics for strange fruit by billie holiday are barely 100 words long, yet they arguably did more to kickstart the American civil rights movement than almost any speech of that decade.

Abel Meeropol wrote it. He was a white, Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx who saw a photograph of a lynching in Indiana and couldn't sleep. He published it first as a poem called "Bitter Fruit" under the pseudonym Lewis Allan. It eventually found its way to Barney Josephson, the owner of the first integrated nightclub in NYC, and then to Holiday.

✨ Don't miss: Movies in Portland Oregon: Why Our Cinema Scene Beats Everywhere Else

The impact was immediate. And terrifying.

Why the lyrics for strange fruit by billie holiday feel like a horror movie

The brilliance of the song—if you can call something so gruesome "brilliant"—lies in the juxtaposition. It uses the language of a pastoral poem to describe a massacre. You hear about the "gallant South" and the "scent of magnolias," but then the hammer drops. Suddenly, you're looking at "bulging eyes and a twisted mouth." It’s visceral.

The song doesn't have a bridge. It doesn't have a chorus. It’s just three stanzas that get progressively more suffocating. When Billie sang it, the lights in the club were turned off except for a single spotlight on her face. The waiters stopped serving. The room went dead silent. If you talked during the song, you were kicked out. Honestly, that’s the only way to process those words. You can’t sip a martini while someone describes "blood on the leaves and blood at the root."

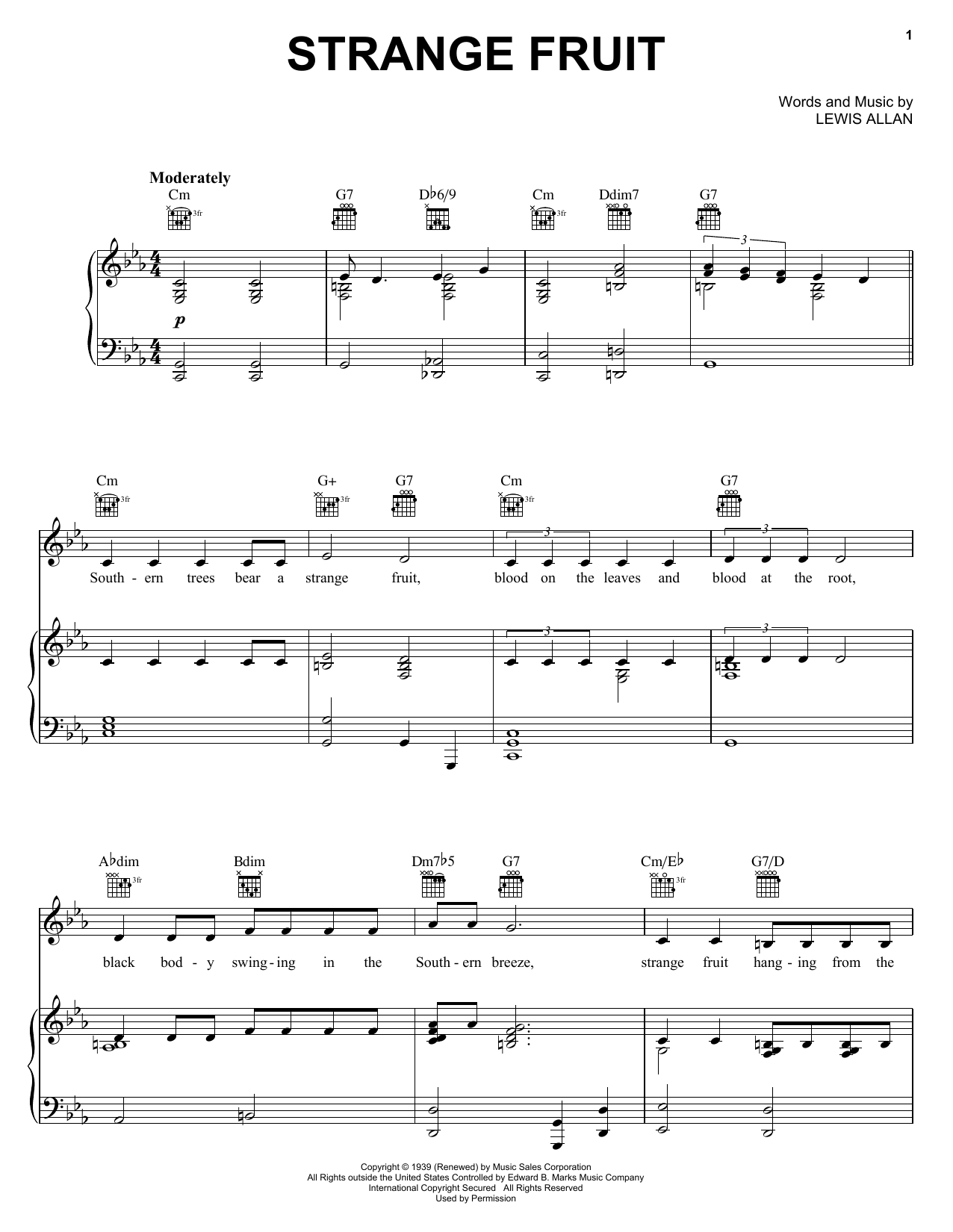

People often forget how much the music matters to the lyrics. The piano introduction is dissonant. It feels unstable. By the time Billie’s voice enters, she’s almost lagging behind the beat, dragging the words out like she’s physically exhausted by the weight of them. She once said the song reminded her of her father, Clarence Holiday, who died after being refused medical treatment at a hospital because of his race. For her, it wasn't just politics. It was personal grief.

The poetic structure of a nightmare

Meeropol was a master of the "reveal." Look at the first stanza. It sets a scene that sounds almost like a travel brochure for the South until the very last word.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

✨ Don't miss: The Truth Behind That Quiz What Naruto Character Are You and Why We Can't Stop Taking Them

The word "fruit" is used as a metaphor for a corpse. It's an image that sticks in your throat. It’s not just death; it’s the casualness of it. The idea that these bodies are just part of the landscape, like apples or pears, is what makes it haunt you. It’s about the normalization of violence.

The backlash and the ban

Not everyone was a fan. Columbia Records, Holiday’s label at the time, refused to record it. They were scared of the reaction from their southern distributors. They thought it was too provocative. They weren't wrong.

Billie had to get a special release from her contract just to record it with Commodore, a smaller, jazz-focused label. Even then, radio stations wouldn't play it. It was banned in parts of the United States. In the UK, the BBC initially wouldn't touch it. It was "too depressing." Or maybe it was just too true.

The FBI took notice, too. Harry Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, hated the song. He hated Billie. He used her heroin addiction as a weapon to silence her, specifically because she wouldn't stop singing "Strange Fruit." He saw the song as a spark for racial unrest. In his mind, a Black woman singing about lynching to a room full of white people was a threat to the social order. He wasn't entirely wrong about the power of the performance. It did change people.

A song that refused to die

Over the years, dozens of artists have tried to cover it. Nina Simone did a version that feels like a funeral march. Kanye West sampled it on "Blood on the Leaves," though many critics felt he stripped away the political weight for a song about a breakup.

But nobody touches the original.

Billie’s voice has this specific "crack" in it. It’s the sound of someone who has seen too much. When she reaches the final line—"Here is a strange and bitter crop"—her voice rises and then cuts off abruptly. There is no resolution. The song doesn't provide comfort. It just leaves you standing in the dark.

Understanding the context of 1939

To understand the lyrics for strange fruit by billie holiday, you have to understand the era. In 1939, lynching was still a common practice. The federal government had failed to pass anti-lynching legislation multiple times. Black soldiers were fighting for democracy abroad while being denied it at home.

The song forced white audiences to look at the reality of the Jim Crow South. It brought the "strange fruit" into the sophisticated clubs of Manhattan. It made it impossible to ignore.

Some people argue that Meeropol, as a white man, shouldn't have been the one to write it. But Meeropol was a communist and a social activist. He believed in using art as a weapon for the working class. He saw the struggle of Black Americans as intrinsically linked to the struggle against fascism and oppression everywhere. His lyrics didn't try to "speak for" the victims as much as they tried to force the observer to acknowledge their own complicity.

The legacy of the "Bitter Crop"

The song became the "Marseillaise" of the civil rights movement. It paved the way for "A Change is Gonna Come" and "Mississippi Goddam." It proved that popular music didn't always have to be about romance or dancing. It could be about justice.

Even today, the song feels uncomfortably relevant. Every time a video of police brutality goes viral, "Strange Fruit" starts trending again. The "blood at the root" hasn't been washed away.

How to engage with the song today

If you’re just reading the lyrics, you’re only getting half the story. You have to hear it. But don't just put it on as background music. That’s a mistake.

- Listen to the 1939 Commodore recording. This is the definitive version. It’s raw. It’s unfiltered.

- Read the history of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. Understanding why the law failed for so long adds a layer of frustration to the lyrics that is essential for context.

- Compare it to Nina Simone's 1965 version. Simone adds a sense of righteous anger that differs from Holiday's mournful, weary delivery. It shows how the civil rights movement shifted from sorrow to demand.

- Watch the footage. There is very little video of Billie singing it, but the few clips that exist show the sheer physical toll it took on her to perform it.

The lyrics for strange fruit by billie holiday aren't just a piece of music history. They are a mirror. They ask us what we are willing to see and what we are willing to ignore. The song ends, but the silence that follows it is where the real work begins.

When you listen, don't look for a catchy melody. Look for the truth. It's usually ugly. It's usually uncomfortable. But as Billie showed us, it's the only thing that actually matters.

📖 Related: The Johnny and June Carter Cash Relationship: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insight

To truly grasp the weight of this piece, research the history of the NAACP's "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday" flag, which was flown from their New York headquarters during the same era. Understanding the visual landscape of 1930s protest will deepen your appreciation for why Holiday's vocal performance was considered an act of extreme rebellion. For further study, read Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Cafe Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights by David Margolick, which provides the most exhaustive account of the song's creation and cultural impact.