You’ve probably seen the quote on a coffee mug or a Pinterest board. "Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances." It sounds like a catchy slogan for a self-help seminar. But when Viktor Frankl wrote those words, he wasn't sitting in a posh cafe in Vienna. He was starving, shivering, and watching his world burn in the Nazi death camps.

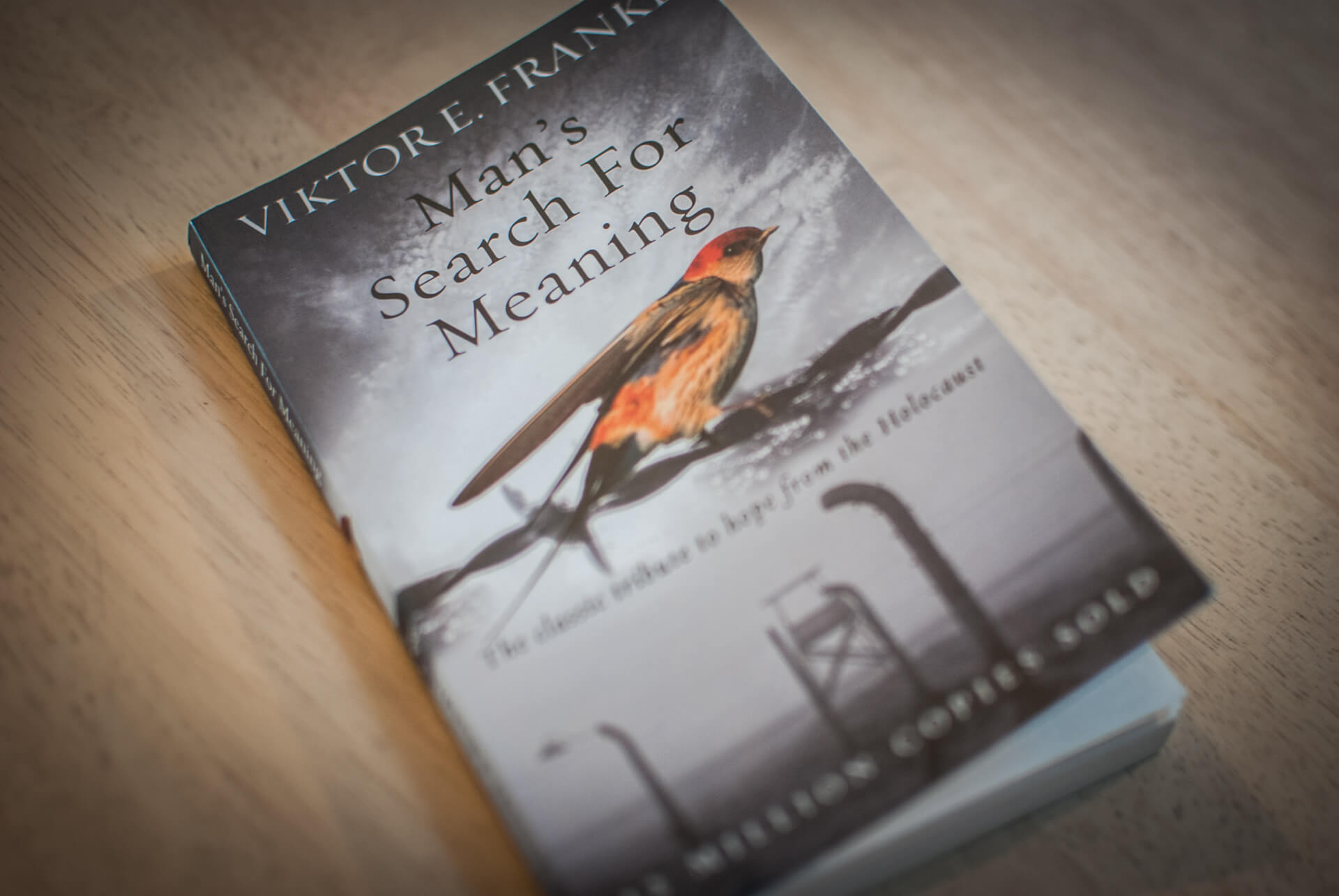

Man’s Search for Meaning isn't just a book. Honestly, it’s a psychological autopsy of the human soul under the most extreme pressure imaginable.

Most people think this is a book about "thinking positive." That’s actually a huge misconception. Frankl wasn't a fan of forced optimism. He was a psychiatrist who realized that the people who survived weren't necessarily the strongest or the healthiest. They were the ones who had a "why."

📖 Related: Is Brie Cheese Healthy? The Truth About That Creamy Rind and Your Heart

The Brutal Reality of the Camps

Frankl spent three years in various concentration camps, including Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. He describes the experience in three distinct psychological phases. First, there’s the shock of admission. Then comes apathy, a kind of emotional death where you stop feeling anything because feeling too much would kill you. Finally, there's the depersonalization after liberation, where the world feels like a dream and you don’t know how to be a person anymore.

He noticed something weird in the camps. The "tough guys"—the ones who relied on physical dominance—often broke first.

But the people who had a rich inner life? They often fared better. They would have "conversations" with their wives in their heads. They would find a weird, dark humor in their situation. They would look at a sunset over the Bavarian woods and feel a brief, sharp sense of beauty. It sounds crazy, but that mental escape was a survival mechanism.

The Three Sources of Meaning

Frankl didn't believe meaning was some grand, mystical thing you find on a mountain top. He argued that we find it in three very practical ways:

- Work or Deeds: Creating something or doing a task that matters. For Frankl, it was the hope of rewriting his lost manuscript on logotherapy.

- Love: Connecting with another person. He survived by thinking of his wife, Tilly, not even knowing if she was still alive (she wasn't).

- Suffering: This is the hard one. If you can't change the situation, you can change your attitude toward it.

He often quoted Nietzsche: "He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how." That’s the core of his whole philosophy.

Why Logotherapy Changed Everything

Before Frankl, psychology was mostly about Freud (the "will to pleasure") or Adler (the "will to power"). Frankl introduced the "will to meaning." He called his approach Logotherapy, from the Greek word logos.

Basically, he argued that we aren't just a collection of drives and instincts. We are beings who crave purpose.

When we don't have that purpose, we fall into what he called the "existential vacuum." You’ve probably felt it. It’s that boredom, that sense of "what's the point?" that leads to depression, aggression, or addiction.

What People Miss About the "Auschwitz" Connection

There’s a bit of a historical debate here. Some critics, like Timothy Pytell, have pointed out that Frankl was only in Auschwitz for a few days—mostly in a "depot" section—before being moved to subcamps of Dachau. Some say he exaggerated his time there to boost the book's authority.

But does it matter?

Whether he was in the main camp for three days or three years, the psychological insights remain the same. He saw the "Muselmänner"—the prisoners who had given up, who had no "why" left, and who died shortly after losing that spark. He saw the Capos, prisoners who turned into monsters to survive. He saw the "saints" who gave away their last piece of bread.

His laboratory was the most horrific place on earth, and his data was human survival.

Dealing With the "Existential Vacuum" Today

You don't need to be in a camp to feel the weight of life. In 2026, we have more comfort than ever, yet more "meaningless" distress. We try to fill the hole with Netflix, doomscrolling, or buying things we don't need. Frankl would call this a failure to answer the question life is asking us.

👉 See also: Walmart Pharmacy Alliance Ohio: Why Your Prescription Access Just Changed

He flipped the script on the "Meaning of Life."

Instead of asking, "What is the meaning of my life?" we should realize that life is asking us that question. We are the ones being interviewed. Every day, every hour, we have to answer with our actions, not our words.

How to Apply This Right Now

If you're feeling stuck, Frankl’s work offers some pretty gritty, actionable advice. It’s not about "manifesting" or "vibes." It’s about responsibility.

- Find your "Why" for the next hour. Sometimes the grand purpose is too big. What is the one thing you need to do right now that matters? Is it finishing a project? Being present for your kid? Just getting through a tough day with dignity?

- Practice "Paradoxical Intention." This is a cool Logotherapy trick. If you're terrified of something—say, public speaking—try to be as nervous as possible. Try to sweat more. Try to shake more. By leaning into the fear instead of fighting it, you often break its power over you.

- Acknowledge the space. Between the thing that happens to you (the stimulus) and how you act (the response), there is a tiny gap. That gap is where your freedom lives. If someone cuts you off in traffic, you have a split second to decide if you're going to be a jerk or just let it go. That’s where you practice being a human.

Man’s Search for Meaning reminds us that we aren't just victims of our environment. We are self-determining. Even when everything—your clothes, your hair, your name, your family—is stripped away, you still own your response.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your "Existential Vacuum": Identify the times in your day when you feel the most aimless or bored. Replace one mindless habit (like scrolling) with a "creative value"—something you build or do.

- Reframe a current struggle: Take one difficult situation in your life right now. Instead of asking "Why is this happening to me?", ask "What does this situation require of me?" Write down three ways you can respond with dignity.

- Read the source material: If you haven't read the actual book, do it. It’s short—usually under 160 pages—and it’s a punch to the gut that somehow leaves you feeling more alive.