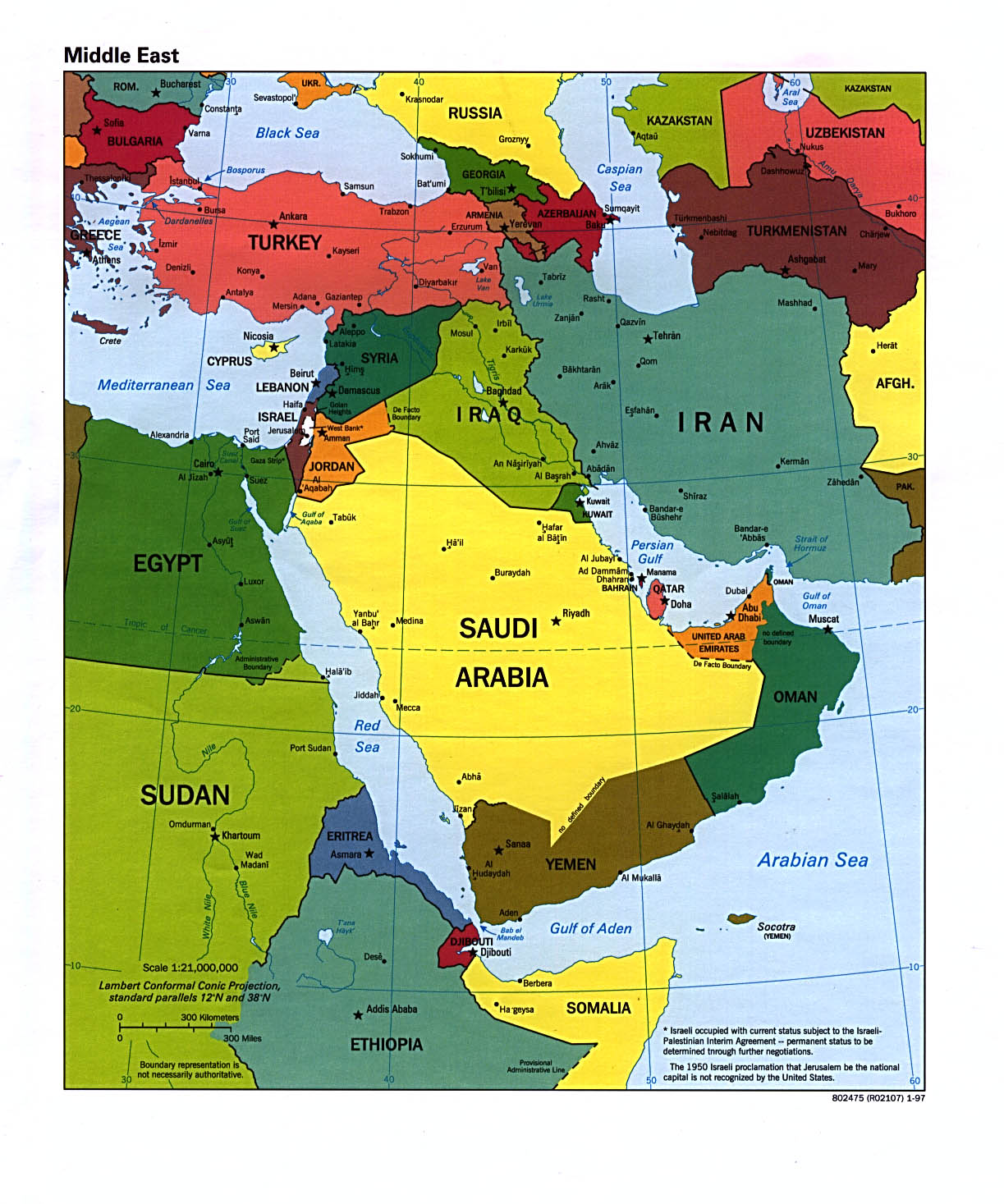

Look at any collection of maps of the Middle East and you’ll notice something weird almost immediately. Straight lines. I mean, look at the border between Egypt and Libya, or the jagged right-angle shapes defining parts of Jordan and Iraq. Nature doesn't work in right angles. Rivers curve. Mountains ridge. Deserts shift. But the maps we use today to define this massive, culturally dense region were largely drawn by guys in suits sitting in European offices who had never stepped foot in the Levant or the Arabian Peninsula.

It's a mess. Honestly, it’s a miracle the current state of cartography in the region works at all. When we talk about "the Middle East," we aren't even talking about a fixed continent. It’s a term coined by the British India Office in the 1850s. It’s a relative term. Middle of what? East of where? Everything depends on where you’re standing.

The Ghost of Sykes-Picot

If you want to understand why maps of the Middle East look the way they do, you have to talk about Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. It was 1916. The Great War was still raging. These two diplomats—one British, one French—sat down with a map and a grease pencil. They basically carved up the carcass of the Ottoman Empire before it was even dead.

They drew what became known as the "Line in the Sand." It ran from Acre on the Mediterranean coast to Kirkuk in the east. North of the line was French influence (modern Syria and Lebanon). South of it was British (Jordan, Iraq, and Palestine).

The problem? They didn't care about the people. They ignored the Kurds. They ignored the Yazidis. They ignored the centuries-old tribal boundaries that actually dictated how people moved and traded. They just wanted oil access and a clear path to India. This is why, when you look at a modern map, you see "artificial" states. Iraq, for instance, was cobbled together from three distinct Ottoman provinces—Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul—that didn't necessarily want to be a single unit.

The Problem with "The Middle East" as a Label

Some maps include Turkey; some don't. Some include Egypt because it's Arab-majority, even though it's technically in Africa. Then you’ve got the Maghreb—Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia—which are often lumped in under the "MENA" (Middle East and North Africa) tag. It's an elastic definition.

Western cartographers often prioritize political borders. But if you were to look at a topographical map of the Middle East, the story changes. You see the massive Zagros Mountains separating Iran from the Mesopotamian plains. You see the Rub' al Khali, the "Empty Quarter," acting as a natural barrier in the south. These physical features have shaped history far more than a diplomat's pen ever could.

Why Map Borders Keep Shifting

Cartography isn't a dead science. It's active. It's aggressive.

Take the Golan Heights. If you buy a map in the United States, it might look one way. If you buy it in Damascus, it looks entirely different. Maps are political statements. Since the 1967 Six-Day War, the status of this territory has been a flashpoint. In 2019, the U.S. formally recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan, but the United Nations still considers it occupied Syrian territory. Your map’s "truth" depends entirely on your GPS's regional settings.

Then there’s the West Bank and Gaza. Standard maps of the Middle East often use dashed lines or specific colors to indicate "disputed" or "Area A, B, and C" under the Oslo Accords. It’s a cartographic nightmare. How do you map a place where the borders change based on a checkpoint or a new settlement? You can't. Not accurately.

The Kurdish Gap

There are roughly 30 million Kurds. They have a distinct language, culture, and history. They are often called the "largest ethnic group without a state." On most official political maps, "Kurdistan" doesn't exist. Yet, if you travel to Erbil in Northern Iraq, you are very much in a region that functions as its own country. They have their own flag, their own military (the Peshmerga), and their own stamps.

A map that only shows "Iraq" is lying to you about the reality on the ground. This is the danger of relying on official state-issued cartography. It erases people.

Digital Mapping and the "Silicon" Border

Google Maps had a bit of a crisis a few years ago regarding the "Persian Gulf." Some countries in the region insist on calling it the "Arabian Gulf." Google’s solution? If you access the map from certain countries, you see one name. From others, you see the second. If you’re outside the region, you might see both.

This is the new era of maps of the Middle East. Algorithmic cartography.

The map is no longer a static piece of paper. It’s a dynamic, localized piece of software that reinforces the user's worldview. This actually makes understanding the region harder. If we aren't even looking at the same map, how can we talk about the same problems?

- The Nile Factor: Most people forget that Egypt is 95% desert. A map that shows Egypt as a large square is misleading. Population-wise, Egypt is a thin green line along a river.

- The Empty Quarter: Saudi Arabia's borders with Oman and Yemen weren't even fully settled until the late 20th century. Why? Because nobody lived in the deep sand. There was nothing to border.

- Maritime Borders: The next big conflict on maps of the Middle East isn't over land. It's the Eastern Mediterranean gas fields. Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, Lebanon, and Israel are all fighting over where the sea-borders sit.

The Forgotten Maps: Trade and Water

If you really want to understand the Middle East, stop looking at political maps. Look at water maps. Look at the aquifers.

The Disi Aquifer sits under the border of Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Both countries pump from it. When the water runs out, those lines on the map won't matter; the migration patterns will. We are seeing a return to "pre-map" logic. In places like Yemen or Libya, the central government often only controls a few city blocks. The rest of the map is a patchwork of tribal alliances and local militias.

The map says "Libya." The reality says three or four different mini-states.

How to Read a Middle East Map Like a Pro

Next time you look at a map of this region, ask yourself three questions:

- Who published this? (Follow the money/politics).

- Are the borders straight or jagged? (Straight = Colonialism; Jagged = Geography).

- Where is the water? (Water = Power).

We often treat maps of the Middle East as if they are ancient and permanent. They aren't. Lebanon is barely a century old. The United Arab Emirates didn't exist as a unified country until 1971. These are young, vibrant, and often volatile borders.

Actionable Insights for Researching the Region

Don't just rely on one source. To get a true sense of the geography and geopolitics, you need to cross-reference multiple types of data.

🔗 Read more: What's the temperature in Cleveland right now: Why It’s Not Just a Number

- Use NASA Satellite Imagery: Compare political borders with actual human settlement patterns. You'll notice that many borders bisect communities that have existed for a thousand years.

- Consult the Perry-Castañeda Library: The University of Texas at Austin has an incredible online collection of historical maps of the Middle East. Comparing a map from 1910 to one from 1950 is an absolute eye-opener.

- Follow MarineTraffic: If you want to see the "real" borders of power, watch the tankers. The Strait of Hormuz and the Bab el-Mandeb are the most important "lines" in the region, even if they aren't painted on the ground.

- Check Local Sources: Look at how news agencies like Al Jazeera (Qatar) vs. Al Arabiya (Saudi) vs. Haaretz (Israel) depict the same disputed territories. The visual discrepancies tell you more about the conflict than any article could.

The map is not the territory. In the Middle East, that old saying is a matter of life and death. The lines are shifting, the water is drying up, and the digital world is redrawing the boundaries every time you refresh your browser. Understanding the region requires looking past the ink and seeing the people, the resources, and the history that the lines try—and often fail—to contain.