So, let's talk about the time the art world collectively lost its mind over a muscle that makes testicles move. Honestly, if you haven't heard of Matthew Barney, you’ve probably at least seen a stray image of him—maybe he’s scaling the walls of the Guggenheim in a pink kilt, or perhaps he’s sporting prosthetic goat legs. That’s the vibe.

In the mid-90s, Barney embarked on this massive, five-part film project called The Cremaster Cycle. It took eight years to finish. It cost millions. And even now, years later, it remains one of those "you had to be there" moments in contemporary art that people still argue about at dinner parties.

What’s With the Name?

First things first: the name. The "cremaster" is a real muscle. Its primary job is to retract the testicles in response to cold or fear. Barney uses this biological function as a massive metaphor for the moment of "pure potentiality." Basically, it’s that window in embryonic development before a fetus becomes male or female.

He’s obsessed with this state of being "undifferentiated."

The films aren't just movies; they are part of a self-enclosed aesthetic system. Barney wasn't just directing; he was building a universe. He populated it with things like:

👉 See also: The Witch: Part 1. The Subversion: Why This Movie Still Breaks Every Rule in K-Horror

- Goodyear blimps

- Freemason rituals

- Zombified murderers

- Tap-dancing satyrs

It sounds like a fever dream because, frankly, it kind of is.

The Weird Order of Things

You’d think a series numbered 1 through 5 would be released in that order. Not Barney. He’s never been one for the easy path. He released Cremaster 4 first in 1994, then jumped around until finishing with the epic, three-hour Cremaster 3 in 2002.

If you look at the cycle biologically, Cremaster 1 represents the most "ascended" state (total potential), while Cremaster 5 represents the most "descended" or fully formed state. It’s a literal descent from the clouds of Idaho to the thermal baths of Budapest.

Breaking Down the Films (Sorta)

Each installment has its own bizarre flavor. Cremaster 1 feels like a 1930s musical filmed on a football field in Boise. It’s all about chorus girls and symmetry. It’s weirdly peaceful.

Then you get to Cremaster 2, which brings in the story of Gary Gilmore—the real-life murderer who was executed in Utah. Barney plays Gilmore. Oh, and Norman Mailer (who wrote the famous book about Gilmore) plays Harry Houdini. It’s a strange, Western-gothic meditation on legacy and bees. Yes, bees.

Cremaster 3 is the big one. It’s the centerpiece. Filmed inside the Chrysler Building and the Guggenheim Museum, it features Barney as the "Entered Apprentice" undergoing Masonic trials. At one point, legendary sculptor Richard Serra shows up and starts flinging molten lead. It’s visceral, expensive-looking, and deeply confusing if you’re looking for a plot.

The "Pretentious" Elephant in the Room

Critics have been fighting over this work for decades. Some, like Jonathan Jones from The Guardian, called it one of the most brilliant achievements in avant-garde cinema. Others basically called it high-budget self-indulgence.

Is it pretentious? Maybe. But Barney isn't trying to hide his meaning; he’s just using a language most of us don't speak fluently. He mixes high art with his background as a Yale football player. He uses materials like petroleum jelly, self-lubricating plastic, and beeswax to create sculptures that are just as important as the films.

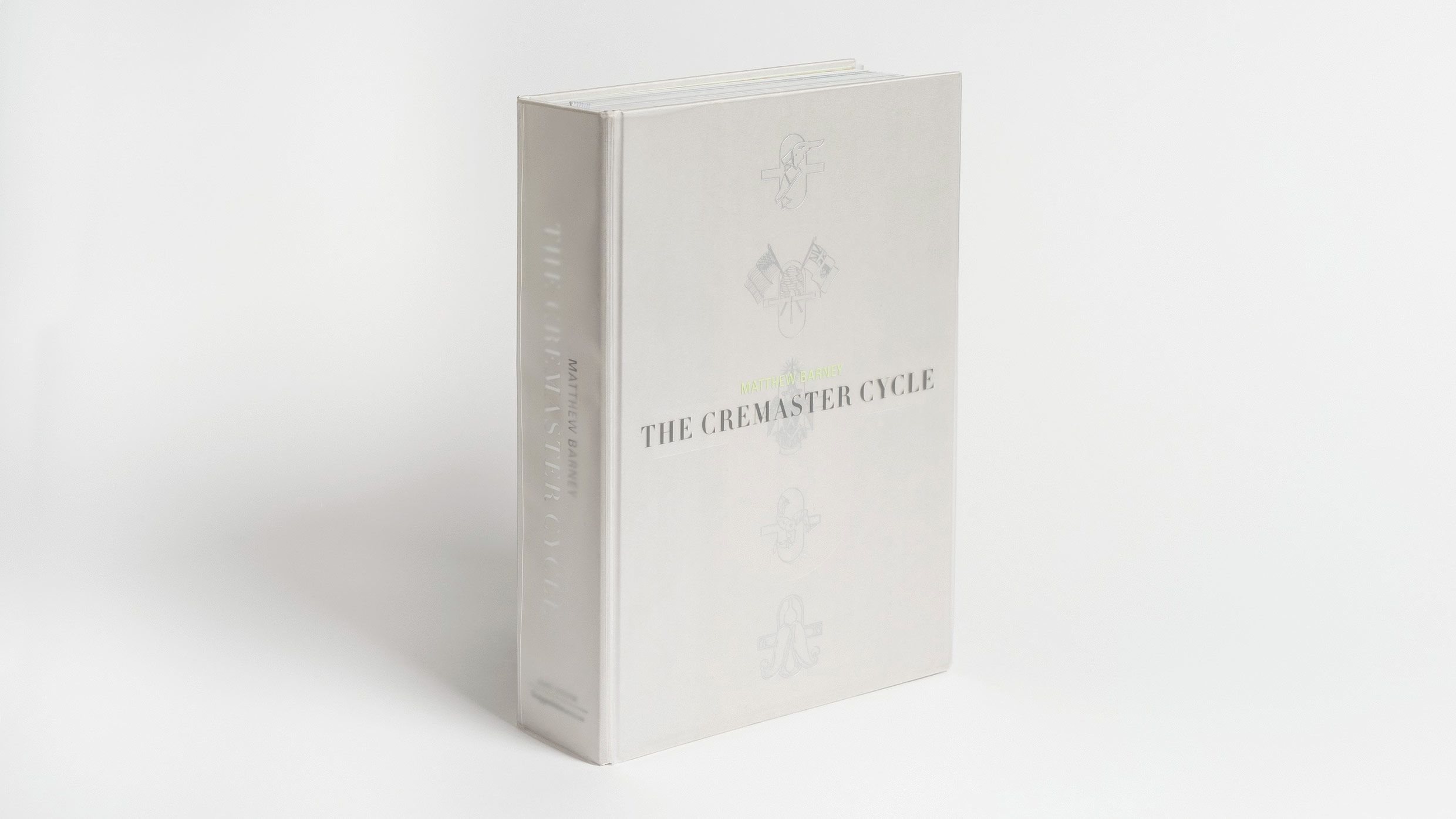

One of the most fascinating things about the Matthew Barney The Cremaster Cycle legacy is its exclusivity. You can't just go on Netflix and stream these. Barney famously released them in limited editions—20 sets of DVDs sold as fine art for six figures each. One disc of Cremaster 2 actually sold for over $500,000 in 2007. It came in a case made of hand-tooled leather and sterling silver.

Why You Should Care Now

We live in an era of "content"—disposable, 15-second clips designed to be scrolled past. Barney’s work is the polar opposite. It’s slow. It’s demanding. It’s huge.

It reminds us that art can be a total world-building exercise. You don't have to "get" every Masonic symbol or biological reference to appreciate the sheer scale of the ambition. Sometimes, just seeing a guy in a tuxedo with a smashed-in face trying to fill a lift with cement is enough to make you stop and think: Wait, what am I actually looking at?

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to actually experience this without dropping half a million dollars, here’s what you do:

- Check Museum Calendars: The Guggenheim and other major institutions occasionally hold screenings. This is the intended way to see them—on a big screen, surrounded by the sculptures.

- Read the Spector Essay: Nancy Spector, the curator who worked closely with Barney, wrote the definitive guide. It breaks down the symbols so you don't feel like you're drowning in metaphors.

- Look at the Sculptures First: Barney considers himself a sculptor first. Look up images of the Chrysler Imperial (2002). Understanding the tactile nature of his materials—the grease, the wax—makes the films feel much more grounded.

- Embrace the Confusion: Don't try to solve it like a puzzle. Treat it like a dream you're having while awake.

The cycle isn't about giving you answers. It’s about the struggle of creation itself. It’s about that moment when a project is still just an idea—pure, messy, and full of potential before the world forces it to become just one thing.