Ever stood on your porch in Midtown, watching the sky turn that nasty shade of bruised-plum green, while your phone says it’s just a light drizzle? It's frustrating. You’re looking at the Memphis doppler weather radar on a tiny screen, trying to figure out if you need to shove the kids into the hallway or if it's just another noisy summer thunderhead.

The truth is, Memphis is a weird spot for weather tracking. We sit in a geographic "sweet spot" for some of the most violent straight-line winds and tornadoes in the country, yet most people don't actually know how to read the data coming off the KNQA station. That’s the official designation for the National Weather Service radar located over in Millington. If you’re relying on a pretty color-coded map from a free app, you're getting a filtered, delayed, and often "smoothed" version of reality.

It’s actually dangerous.

Understanding the Millington Eye

The heart of the Memphis doppler weather radar system is the WSR-88D, situated at the Millington Naval Air Station. It’s part of a massive national network, but it has its quirks. Radar works by sending out a pulse of energy. That energy hits something—rain, hail, a rogue flock of birds—and bounces back. The "Doppler" part is what matters for us in the Mid-South. It measures the shift in frequency to tell us if that rain is moving toward the radar or away from it.

Think about a siren. As an ambulance speeds toward you, the pitch climbs. As it passes, it drops.

That is exactly how we spot rotation. In Memphis, we look for "couplets." This is where bright red (moving away) and bright green (moving toward) pixels are squeezed right against each other. When you see that over Germantown or Southaven, you aren't looking at rain anymore. You’re looking at a spinning column of air.

But here is the kicker: the radar beam doesn't travel in a straight line relative to the ground. The earth curves. The beam goes up. By the time the signal from Millington reaches Tunica or parts of North Mississippi, it’s looking thousands of feet up into the clouds. It might see a tornado forming in the mid-levels of the storm, but it can’t always see what’s happening at the surface. This is why ground truth—actual humans looking at the sky—remains so vital in Shelby County.

💡 You might also like: Civilization Beyond Earth: Why We Haven’t Found Anyone Yet

Why Base Reflectivity Isn't Enough

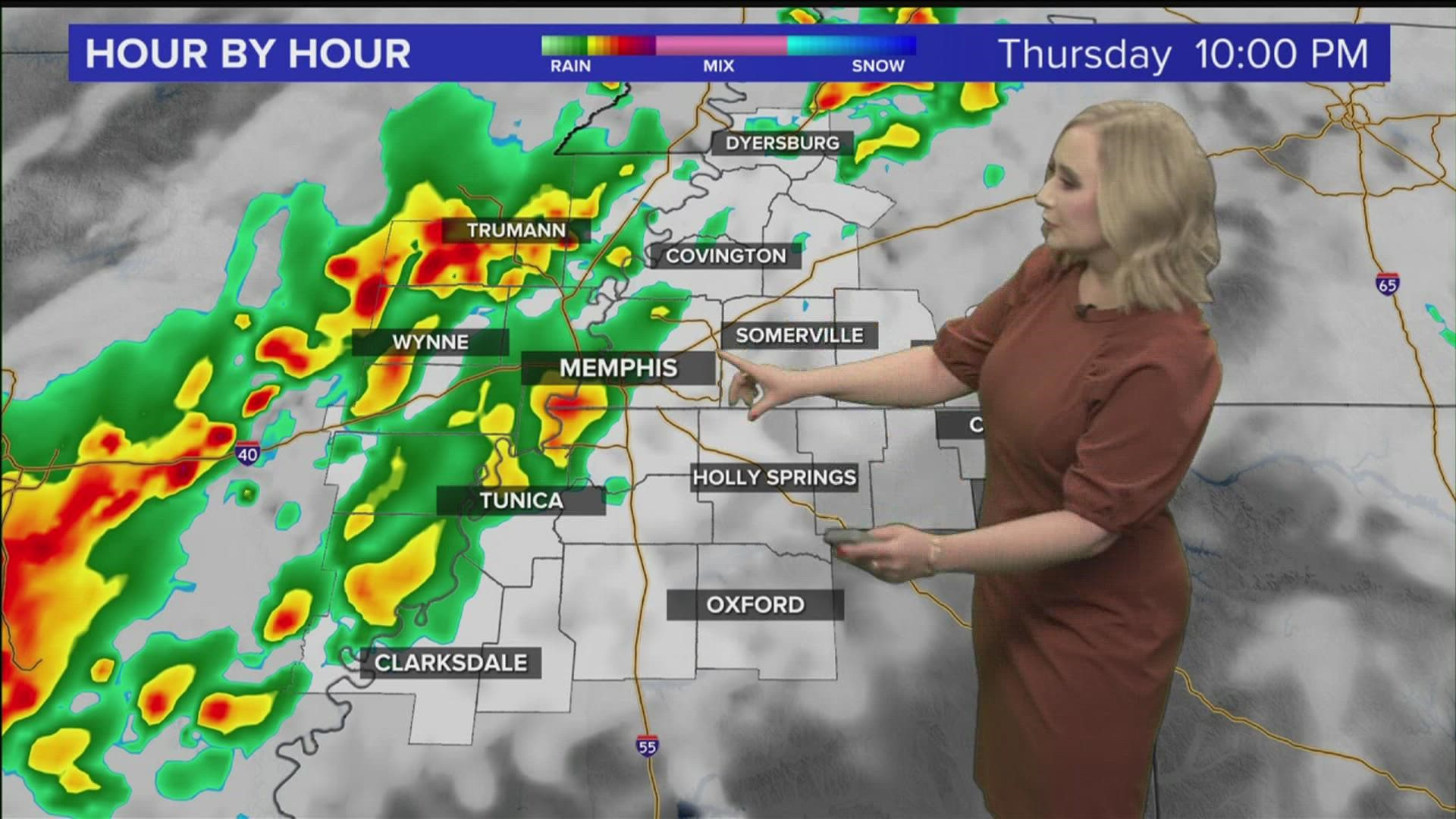

Most people just look at "Base Reflectivity." That’s the standard rainbow map. Green is light rain, yellow is moderate, and red is heavy. If you see purple or white, it’s probably hail or extremely intense downpours that cause flash flooding on Union Avenue in minutes.

However, if you want to survive a Memphis spring, you have to look at "Storm Relative Velocity."

Velocity data looks like a mess of red and green. It isn't pretty. But it’s the only way to see the wind. In 2023, when those massive straight-line winds ripped through the city, the "rain map" didn't look nearly as terrifying as the velocity data. Velocity showed 80 mph winds just a few hundred feet above the treetops.

Reflectivity tells you what is falling. Velocity tells you where the energy is going.

You also have to watch out for the "Cone of Silence." Since the Memphis doppler weather radar is in Millington, it can't see what's directly above itself. If a storm is sitting right on top of the radar site, the beam passes through the sides of the storm but misses the core. If you live in Millington and the radar looks clear while the wind is screaming, you're likely in that blind spot.

The Problem with Mobile Apps

Your favorite weather app is probably lying to you by about five minutes.

That sounds small. It isn't. In a tornadic situation, a storm can move two or three miles in five minutes. If you’re looking at a "delayed" Memphis doppler weather radar feed, the hook echo you see on your screen might already be on top of your house.

Most free apps "smooth" the data. They take the raw, blocky pixels from the NWS and turn them into soft, flowing gradients. It looks high-tech. It looks modern. It’s actually garbage. Smoothing hides the "noise" that often signals a debris ball—the literal signature of a tornado picking up pieces of houses and trees.

If you want the real deal, you use something like RadarScope or Gibson Ridge. These apps give you the raw data directly from the Level II feed. It’s not pretty. It’s blocky and technical. But it’s the same data the meteorologists at the NWS office on Demo Memphis use.

Spotting the Correlation Coefficient

This is the "secret" tool of modern weather geeks. It’s called Correlation Coefficient (CC).

Essentially, CC measures how "alike" the things in the air are. Raindrops are all pretty much the same shape. If the radar sees uniform shapes, the CC map is a solid, bright red. But if a tornado touches down and starts tossing shingles, plywood, and fiberglass insulation into the air, those things are all different shapes.

The CC map will suddenly show a blue or yellow drop in the middle of the red. That’s a "Debris Ball."

When you see a velocity couplet (the red and green together) and a CC drop in the same spot, it is no longer a "radar indicated" threat. It is a confirmed tornado on the ground doing damage. In Memphis, where trees are heavy and visibility is often blocked by buildings or rain, this technology saves lives.

Real-World Limitations

Let’s talk about the "Radar Gap."

The Memphis radar is great for Shelby County. But move further east toward Jackson, Tennessee, or south toward the Mississippi Delta, and things get dicey. The beams from Memphis, Little Rock, and Columbus, Mississippi, all start to get very high off the ground by the time they reach those areas.

This means a low-level tornado—the kind that stays under 1,000 feet—might not even show up on the Memphis doppler weather radar if it’s far enough away. It’s a terrifying blind spot that meteorologists have been screaming about for years.

Also, we have "attenuation." If a massive storm is sitting between the radar in Millington and your house in Collierville, the heavy rain can actually soak up the radar beam. The radar might show a weaker storm behind the first one because the signal couldn't punch through the heavy stuff. It's like trying to shine a flashlight through a thick wool blanket.

How to Actually Use This Information

When the sirens go off in Memphis, don't just look at the rain map. Open a raw data feed. Check the velocity.

- Locate the KNQA station. Know where you are in relation to Millington.

- Toggle to Velocity. Look for where the brightest reds meet the brightest greens.

- Check for the Hook. In base reflectivity, look for a "p-shape" or a hook dangling off the southwest corner of a storm cell.

- Verify with CC. If there’s a "hole" in the Correlation Coefficient in the same spot as your hook and your velocity couplet, get in the basement or the interior room immediately.

The Memphis doppler weather radar is a beast of a machine, but it’s just a tool. It requires a human brain to interpret the noise. Don't trust the automated "storm tracks" that apps draw; those are often based on old algorithms that can't predict the sudden "left turns" that Memphis storms are famous for.

Stay weather-aware. Watch the raw data.

Actionable Next Steps

- Download a Pro Tool: Stop relying on the default weather app that came with your phone. Download RadarScope or RadarOmega. These apps cost a few dollars but provide the raw Level II NEXRAD data without the dangerous smoothing.

- Identify Your Radar Site: Set your primary station to KNQA (Memphis/Millington), but keep KGWX (Columbus, MS) and KLZK (Little Rock, AR) as backups. If the Memphis radar takes a lightning strike and goes offline—which happens—you’ll need the "long-range" views from neighboring states to see what’s coming across the river.

- Learn the VCPs: Understand that the radar changes its "Volume Coverage Pattern" during storms. In clear weather, it spins slowly. In severe mode, it tilts and spins much faster to give you updates every 60-90 seconds. If you notice your map updating faster, the NWS has officially triggered "Severe" mode.