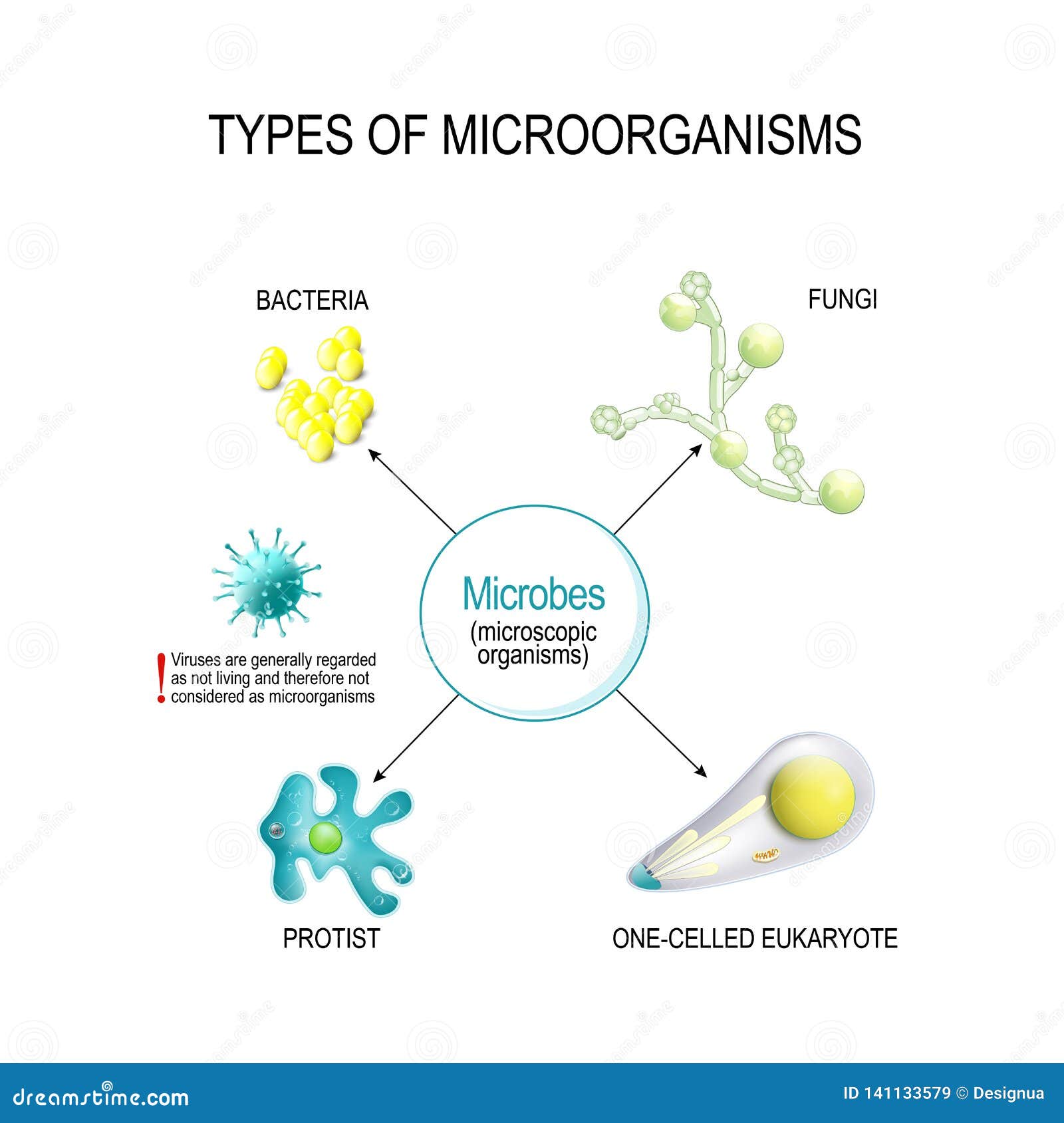

You probably think you're alone in the room right now. You aren't. Honestly, you're outnumbered by about a trillion to one, and most of your "guests" are literally living on your eyelashes or deep inside your gut. Microorganisms aren't just these invisible germs that make you sneeze or give you food poisoning from that questionable tuna salad. They are the architects of the planet. Without them, the atmosphere wouldn't have oxygen, your garden would be a pile of dead, un-rotting sticks, and you definitely wouldn't have cheese. Life is small. It's also incredibly diverse, and when we talk about the different categories of microorganisms, we’re looking at organisms so fundamentally different from each other that a human is more genetically similar to a mushroom than some of these microbes are to one another.

Bacteria: The World’s Most Successful Roommates

Bacteria are the OGs. They’ve been here for about 3.5 billion years, which makes us look like brand-new interns in the history of Earth. Most people hear "bacteria" and immediately think of Salmonella or Staphylococcus, but that's like judging the entire human race based on one bad neighbor.

Bacteria are prokaryotes. This is just a fancy way of saying they don't have a nucleus to hold their DNA; it just floats around in a tangled mess called a nucleoid. They come in three basic shapes: spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), and spirals (spirilla). It's simple, but it works. Take Escherichia coli. Most strains are harmless and live in your intestines, helping you produce Vitamin K. But then you have Vibrio cholerae, which can dehydrate a person to death in hours.

The scale of their influence is wild. You have more bacterial cells in and on your body than you have actual human cells. Recent research, including studies published in Nature, has slightly revised that "10-to-1" ratio people used to quote—it's likely closer to a 1-to-1 ratio—but the point stands. You are a walking ecosystem. In the soil, bacteria like Rhizobium "fix" nitrogen, taking it from the air and turning it into a form plants can actually use. No Rhizobium, no crops, no dinner.

Archaea: The Weird Cousins Who Like It Hot

For a long time, scientists just lumped Archaea in with bacteria because they look similar under a microscope. Big mistake. In 1977, Carl Woese and his team at the University of Illinois realized that these guys are genetically so distinct they deserve their own "Domain."

Archaea are famous for being extremophiles. They love the places where everything else dies. We're talking about the boiling, acidic vents at the bottom of the ocean or the literal salt flats of the Dead Sea. Pyrococcus furiosus grows best at 100°C—the boiling point of water. If you put it in a lukewarm bath, it would literally freeze to death.

But here’s the kicker: they aren't just in volcanoes. They’re everywhere. They live in the open ocean and even in your own mouth. Interestingly, no known Archaea actually cause disease in humans. They just sort of hang out, processing methane or sulfur, minding their own business. They’re basically the goths of the microbial world—misunderstood, obsessed with extreme environments, and totally harmless to your health.

Fungi: The Recyclers

Fungi are a bit of a curveball in the categories of microorganisms. Unlike bacteria, they are eukaryotes. Their cells look a lot more like ours, complete with a nucleus and complex internal machinery. While we usually think of mushrooms, the "micro" part refers to yeasts and molds.

Yeasts are single-celled powerhouses. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is basically the reason for civilization; it's the yeast used for baking bread and brewing beer. Without its ability to ferment sugar into CO2 and ethanol, our diets would be much more boring.

Then you have the molds. Penicillium chrysogenum changed the world when Alexander Fleming left a Petri dish out by mistake in 1928. That "mold juice" became Penicillin, the first true antibiotic. On the flip side, you have things like Candida albicans, which can cause yeast infections if your internal microbiome gets out of whack. Fungi are essentially nature's cleanup crew. They secrete enzymes that break down tough organic matter like lignin in wood. If fungi stopped working tomorrow, the world would be buried under miles of un-decomposed trees and dead leaves within a few decades.

Protists: The "Everything Else" Drawer

If a scientist finds a microbe that isn't a bacterium, a fungus, or an archaeon, they usually chuck it into the Protist category. It’s the biological equivalent of that one kitchen drawer full of loose batteries, rubber bands, and old menus.

Protists are incredibly diverse. You have the plant-like ones, like Algae. These range from microscopic diatoms with glass-like shells to giant kelp (though the tiny ones are the true microorganisms). Diatoms alone produce about 20% of the oxygen we breathe. Think about that next time you take a breath; a tiny swimming cell in the ocean probably made that air for you.

Then you have the animal-like protists, often called Protozoa. Amoeba proteus crawls around by stretching its body into "false feet" (pseudopodia). Plasmodium is much more sinister—it's the protist responsible for malaria, transmitted through mosquito bites. It’s a complex group. Some hunt, some photosynthesize, and some, like Euglena, actually do both depending on whether the sun is out.

Viruses: Are They Even Alive?

This is the big debate in biology. Viruses are essentially just genetic "instruction manuals" (DNA or RNA) wrapped in a protein coat. They can't reproduce on their own. They can't eat. They don't breathe. They just wait.

A virus like the Influenza virus or SARS-CoV-2 needs to hijack a host cell to make copies of itself. Once inside, it turns the cell into a virus factory until the cell eventually bursts or wears out. Because they lack their own metabolism, many scientists don't consider them "living" organisms, but rather "biological entities."

🔗 Read more: Is Gatorade Gluten-Free? What You Actually Need to Know Before Your Next Workout

However, they are undeniably part of the microbial landscape. Bacteriophages—viruses that specifically hunt and kill bacteria—are the most abundant biological entities on Earth. There are an estimated $10^{31}$ phages on the planet. They play a massive role in controlling bacterial populations. In a weird way, the enemy of our enemy (bacteria) might be our friend; researchers are currently looking at phage therapy as a way to kill antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

Microscopic Animals: Tiny But Mighty

Finally, we have the "micro-animals." These are multicellular, but you still need a microscope to see them. The most famous is the Tardigrade, or "Water Bear."

Tardigrades are practically indestructible. They can survive the vacuum of space, extreme radiation, and being frozen to nearly absolute zero. They do this by entering a state of "cryptobiosis," where they dry out and stop their metabolism entirely. When you add water, they just wake up and walk away.

Then there are Rotifers. They have a ring of cilia around their mouths that rotates like a wheel to sweep food in. They are complex creatures with nervous systems and digestive tracts, all packed into a body smaller than some single-celled protists. It’s a reminder that complexity doesn't always require size.

Why This Matters For Your Health

Understanding these different categories of microorganisms isn't just an academic exercise. It changes how you live. For example, taking an antibiotic kills bacteria, but it does absolutely nothing to a virus like the common cold. In fact, overusing them can wipe out your "good" bacteria, allowing fungi like Candida to take over.

The "Hygiene Hypothesis" suggests we might actually be too clean. By scrubbing away every microbe with antibacterial wipes, we might be preventing our immune systems from learning how to distinguish between a real threat and a harmless pollen grain, potentially leading to the rise in allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Actionable Takeaways for Microbe Management

- Diversify your gut: Eat fermented foods like kimchi, kefir, or sauerkraut. These are loaded with live Lactobacillus and other helpful bacteria that reinforce your internal ecosystem.

- Respect antibiotics: Only use them for bacterial infections, and always finish the full course. Stopping early allows the strongest bacteria to survive and mutate into resistant strains.

- Feed your friends: Bacteria need "prebiotics"—basically fiber—to thrive. Onions, garlic, and bananas are like a five-star buffet for your gut microbiome.

- Don't fear the dirt: Moderate exposure to nature (and the microbes in soil) can help prime a child's immune system. You don't need to sterilize the entire world.

- Check the labels: "Antimicrobial" and "Antibacterial" mean different things. Use the right tool for the job to avoid creating resistant "superbugs" in your own kitchen.

The microbial world is a messy, invisible, and fascinating place. We aren't just living among these different categories of microorganisms; we are fundamentally intertwined with them. Every breath, every bite of food, and every day you spend healthy is a testament to the hard work of trillions of tiny organisms you'll never actually see.