You’re trying to change something. Maybe it’s a local zoning law, a corporate policy, or how your school board spends its money. You have a small group of fired-up people, a lot of passion, and absolutely no idea what to do next Monday. So, naturally, someone suggests a protest. Or a petition. Or a viral TikTok.

Stop.

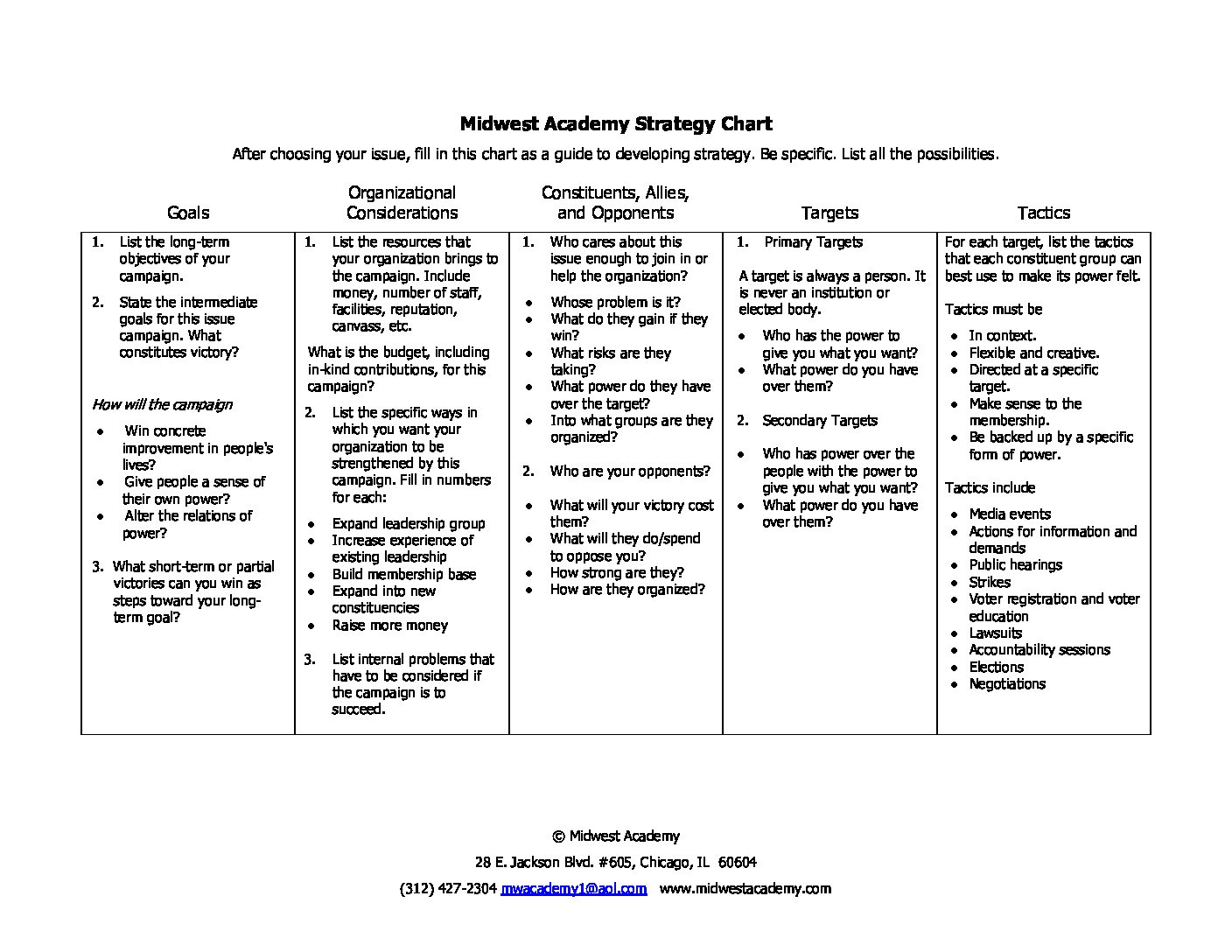

Honestly, jumping straight to tactics is how most campaigns die before they even start. If you don't have a plan to actually move the person who can say "yes," you’re just making noise. That’s where the Midwest Academy Strategy Chart comes in. Created by the Midwest Academy—a legendary training school for progressive organizers founded in the early 70s by folks like Heather Booth—this chart is basically the "North Star" for anyone trying to build power and win.

It’s not just a worksheet; it’s a way of thinking that forces you to be honest about what you have, what you want, and who is actually standing in your way.

Why the Midwest Academy Strategy Chart Still Matters

Most people think of "strategy" as some vague, high-level corporate jargon. In the world of community organizing, strategy is much more literal: it's how you get from point A to point B when you don't have a billion dollars.

📖 Related: ASE A2 Test Prep: What Most Mechanics Get Wrong About Automatic Transmissions

The Midwest Academy Strategy Chart is essentially a five-column logic model. It connects your goals to your tactics so you aren't just doing "busy work." If a tactic doesn't directly help you reach a goal or build your organization, the chart exposes it as a waste of time. It’s brutal like that.

Column 1: The Goals (What Do You Actually Want?)

You can’t just say "we want justice." That’s a vibe, not a goal. In this chart, goals are broken down into three specific buckets:

- Long-term: The big vision. Ending homelessness in your city.

- Intermediate: The specific policy change you’re fighting for right now. Passing a "Right to Counsel" law for tenants facing eviction.

- Short-term: The "partial victories" that keep people motivated. Getting a committee hearing or a public statement from a key council member.

The genius here is that the chart forces you to define a win. If you don’t know what a victory looks like, you’ll never know when to stop or how to pivot.

Column 2: Organizational Considerations

This is the reality check. You have to list your resources. How much money is in the bank? Who are your leaders? Do you have an email list of 50 people or 5,000?

Kinda importantly, this column asks: How will this campaign build your organization? If you win the policy but your group falls apart afterward because everyone is burnt out, you didn't really win. A good strategy makes the group stronger, larger, and more famous by the time the campaign ends.

Column 3: Constituents, Allies, and Opponents

Who cares about this?

You need to list the people who are directly affected by the problem. These are your constituents. Then you have allies—people or groups who might not be directly affected but will stand with you.

Then there are the opponents. You’ve got to be real about who is going to spend money and time to stop you. What is your victory going to cost them? If you’re fighting for a higher minimum wage, the local chamber of commerce isn't going to send you a Christmas card. You need to know their power as well as your own.

Column 4: The Targets (The "Who" is a Person)

This is the part most people get wrong. A target is never "the government" or "the system." You can't lobby a building.

A target is always a person.

✨ Don't miss: Abercrombie and Fitch Stock Symbol: What Really Happened to ANF

It’s Councilman Smith. It’s CEO Jane Doe. It’s the Superintendent. You need to identify the specific individual who has the power to give you what you want.

Primary vs. Secondary Targets

Sometimes you can't get to the primary target directly. They won't take your calls. That’s when you look for a secondary target—someone who has power over the primary target and who you have power over. Maybe the Mayor won't listen to you, but he definitely listens to the head of the local labor council. That labor leader becomes your secondary target.

Column 5: Tactics (The Fun Part)

Finally, we get to the actions. But here's the catch: a tactic is only good if it’s directed at a target.

If you hold a rally in a park where your target can’t see or hear you, it’s just a party. A real tactic is something your constituents do to the target to make them say "yes." It could be a meeting, a letter-writing campaign, a "bird-dogging" session at a public event, or a media stunt.

The Midwest Academy teaches that tactics should be:

- In the experience of your members. (Don't ask grandma to hack a server).

- Outside the experience of the target. (Surprise them).

- Directed at a person.

Put It Into Practice

Don't just read about it. Grab a giant piece of butcher paper and draw five columns.

🔗 Read more: Trade Freedom for Security: Why We’re Suddenly Rethinking Global Commerce

First, define your intermediate goal—make it "SMART" (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound).

Second, be brutally honest about your "Organizational Considerations." If you only have three volunteers, don't plan a march for 10,000 people.

Third, name your target. Research them. Find out where they live, what they care about, and who they fear.

The Midwest Academy Strategy Chart isn't a magic wand, but it’s the closest thing organizers have to a blueprint. It turns "we should do something" into "we are doing this, to that person, for this reason." And that is how you actually win.

Next Steps for Your Team:

Download a blank template of the chart and set a two-hour meeting with your core leadership. Start with the "Targets" column—if you can't name the person who can solve your problem, your campaign hasn't actually started yet. After you've identified the target, map back to your "Constituents" to see who has the most leverage over that specific individual.