Ever walked into a store and realized the only reason you can buy a simple wooden pencil for a few cents is because thousands of people who don't even speak the same language decided to cooperate? They didn't do it because a government czar told them to. They did it because they wanted to make a buck. That’s the core vibe of Milton Friedman Free to Choose, a book and TV series that basically slapped the 1980s across the face and still manages to ruffle feathers today.

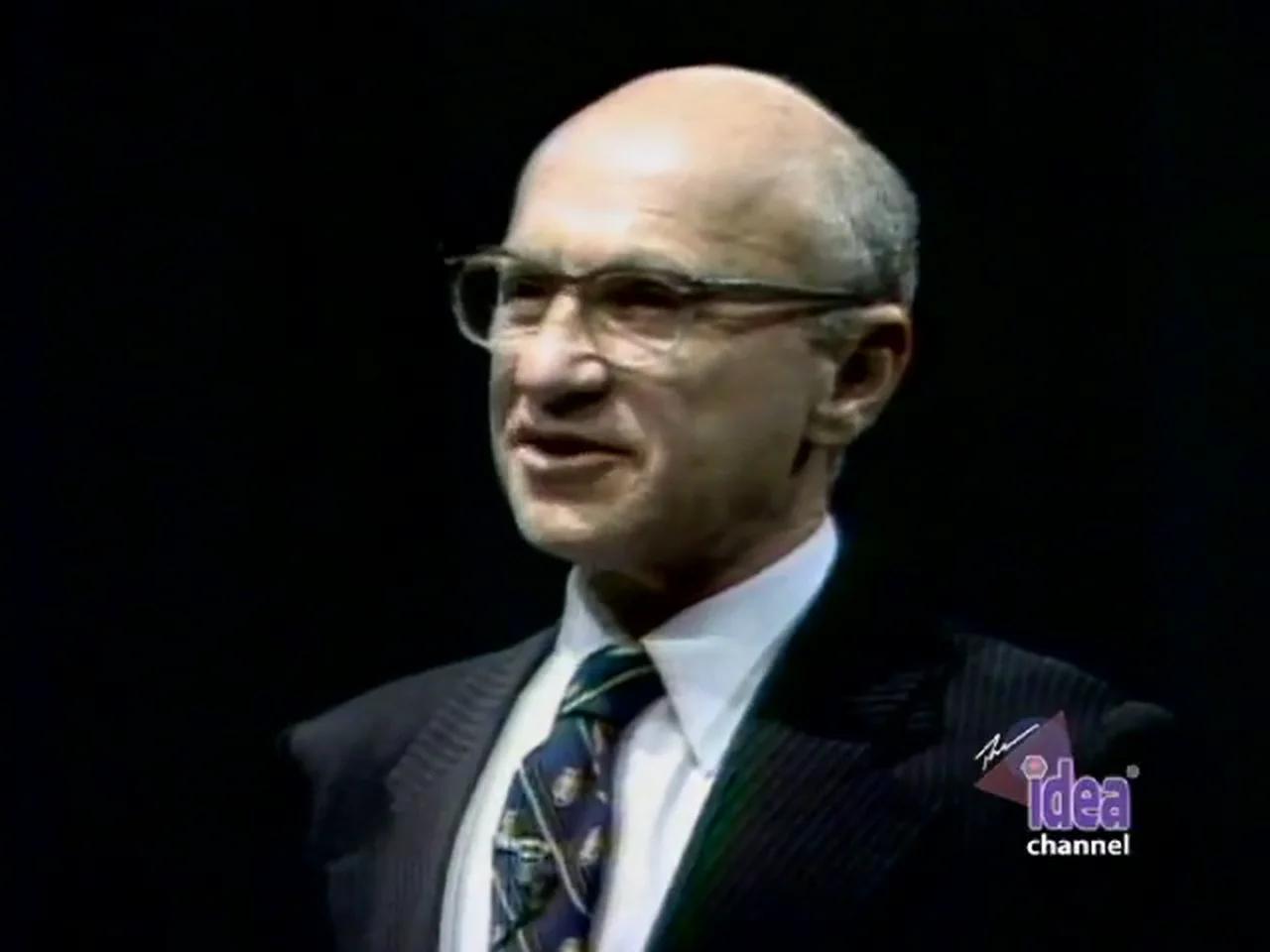

Honestly, most people talk about Friedman like he was some kind of cold, calculating math robot. They think he just cared about corporations making money. But if you actually sit down with the text—or watch those grainy PBS clips of him smiling while he dismantles a socialist's argument—you realize it was always about something else. It was about you. Your choices. Your right to mess up or succeed without a bureaucrat breathing down your neck.

The Pencil and the Hidden Magic of Markets

Friedman loved the story of the pencil. He borrowed it from Leonard Read. Think about it: no single person on Earth knows how to make a pencil. The guy cutting the cedar in Oregon doesn't know how to mine the graphite in Sri Lanka. The person in the factory making the brass ferrule doesn't know how to grow the rubber tree for the eraser.

They’ve never met. They might hate each other's politics.

Yet, the price system brings them together. When you buy that pencil, you’re seeing a miracle of voluntary cooperation. This is the "Invisible Hand" that Adam Smith talked about, but Friedman made it feel real for the 20th century. He argued that when the government steps in to "help" by setting prices or subsidizing certain industries, they aren't just moving numbers around. They are breaking the communication lines between all those people.

Why the 1980s mattered (and 2026 feels familiar)

When Free to Choose dropped in 1980, the world was a mess. Inflation was eating everyone's savings. Gas lines were a thing. It felt like the "experts" in Washington had lost the manual on how to run a country. Friedman and his wife, Rose, basically said, "Stop trying to run it."

📖 Related: Finding Your Unique Superannuation Identifier: Why Most People Get It Wrong

Milton Friedman Free to Choose: The "Tyranny of Control"

A huge chunk of the book focuses on what they called the "Tyranny of Control." This isn't just about big scary dictators. It’s about the "well-intentioned" stuff. Minimum wage laws. Occupational licensing. The FDA.

Friedman’s take on the FDA is still one of his most controversial points. He didn't just say they were slow; he said they were actually killing people. His logic? If the FDA takes five years to approve a life-saving drug, the people who died in those five years are "invisible victims." No one blames the FDA for the people who didn't get the drug, but everyone screams if a drug is approved and has a side effect. So, the agency naturally slows everything down to protect itself, not you.

He pushed for a system where information flows freely, and you—the consumer—decide what risks are worth it. Kinda wild, right? It sounds extreme to some, but in a world where we now have instant access to reviews and data, his 1980s dream of "informed choice" feels less like sci-fi and more like a missed opportunity.

What Everyone Gets Wrong About "Greed"

One of the biggest myths about Milton Friedman Free to Choose is that it’s a manifesto for greed. You’ve heard the critics. They say Friedman wanted a world of sharks eating minnows.

But listen to what he actually said. He argued that a free market is the only system that doesn't require you to love your neighbor to work with them. In a command economy, you have to do what the person with the gun or the badge says. In a free market, you only get someone's money if you give them something they actually want.

It’s about service.

If I’m a baker, I don't give you good bread because I’m a saint. I do it because if the bread is stale, you'll go to the guy across the street. The market forces me to be "good" even if I'm a jerk. Friedman saw the market as a tool for peace. He literally thought free trade could prevent wars because it’s hard to shoot your best customers.

The School Voucher Idea That Won't Die

Education was Friedman's big passion project. He hated that your zip code determined your school. He saw the public school system as a monopoly. And what do monopolies do? They get expensive and lazy because they have no competition.

His fix? The voucher.

- The government gives the money to the parents, not the school building.

- Parents pick the school that fits their kid.

- Schools have to compete to survive.

Decades later, we’re still arguing about this. In 2026, with the rise of AI-driven micro-schools and home-schooling pods, Friedman’s "choice" model is looking more prophetic than ever. He didn't want to destroy education; he wanted to blow the lid off the "one-size-fits-all" box.

The Dark Side of Good Intentions

The Friedmans were obsessed with "unintended consequences." They looked at the Great Depression and didn't blame the stock market. They blamed the Federal Reserve for letting the money supply collapse. They looked at the "War on Poverty" and saw a system that accidentally trapped people in a cycle of dependency.

👉 See also: The Gucci Family: What Really Happened to the Dynasty Behind the Double G

They argued that when you pay people to be poor, you get more poor people. It sounds harsh. It is harsh. But their solution wasn't to just let people starve. Friedman actually proposed a "Negative Income Tax"—basically a floor that ensured everyone had enough to live, but without the soul-crushing bureaucracy of traditional welfare. It was a weirdly progressive idea for a "conservative" economist.

Is It Still Relevant?

Some people say Friedman is "outdated." They point to the 2008 financial crisis or the supply chain issues of the 2020s. They say markets are too fragile.

But honestly? Look at the most successful parts of your life. It’s usually where you have the most choice. The parts that feel broken—healthcare, housing, higher ed—are usually the places with the most government "meddling" (as Friedman would call it).

He’d probably look at the 2026 economy and say, "I told you so." He’d point to how inflation came back when we printed money like it was Monopoly cash. He’d point to how regulation has made it impossible to build new houses in the cities where people actually want to live.

Actionable Insights: Applying the Friedman Mindset

If you want to take the principles of Milton Friedman Free to Choose and actually use them in 2026, you don't need an economics degree. You just need to change how you look at the world.

- Watch for the "Invisible Victims": Next time you hear about a new regulation that "protects" people, ask yourself: who is being priced out? Who is losing their job because of this? Who is the "invisible" person getting hurt?

- Vote with Your Feet (and Wallet): Monopolies only exist if we let them. Support competition. If a company is acting like a "protected" utility, find an alternative. The most powerful thing you own isn't your vote; it's your choice.

- Question "The Experts": Friedman’s whole thing was that no group of 12 smart people in a room can know more than millions of individuals making their own decisions. Trust your own localized knowledge over a "national strategy."

- Separate Power: The biggest takeaway from the book is that when you mix economic power (money) with political power (the law), you get tyranny. Always push to keep them separate. You don't want the person who regulates the banks to also own the banks.

Friedman wasn't a fan of "ultimately" or "in conclusion" endings, so let’s just put it this way: the world is a messy, complicated place, and the more we try to "plan" it from the top down, the more we break the very things that make it work. Choice isn't just a luxury. It's the engine.