Honestly, if you were standing on the shores of Spirit Lake on the morning of May 18, 1980, you wouldn't have had a prayer. It wasn't just a "volcano eruption" in the way we see them in movies with slow-moving lava you can outrun. It was a total geographic collapse. One minute, you're looking at a peak often called the "Fujiyama of America" because of its perfect, symmetrical snow cap. The next? The entire north face of the mountain is sliding away at 150 miles per hour. It’s still the deadliest and most economically destructive volcanic event in U.S. history, and yet, there’s so much about Mount Saint Helens 1980 that people get wrong when they look back at the black-and-white photos.

Most people think the mountain blew its top. That’s not exactly right. It blew its side. Because of a massive bulge on the north flank—geologists called it "the cryptodome"—the pressure didn't go up like a champagne cork. It went out like a shotgun blast.

The Warning Signs Nobody Wanted to Believe

The lead-up to the disaster was a masterclass in scientific tension. It started in March. A small 4.2 magnitude earthquake rattled the Cascades, and suddenly, the mountain was awake after 123 years of napping. By late March, steam was venting. By April, that weird bulge I mentioned was growing by five feet per day. Imagine that. A literal mountain wall pushing outward because magma is shoving its way through the plumbing.

Government officials were in a tough spot. You had loggers who wanted to keep working the high-yield timber stands. You had cabin owners at Spirit Lake who had lived there for generations. Harry R. Truman—not the president, but the 83-year-old lodge owner—became a folk hero for refusing to leave. He told reporters he was part of the mountain and the mountain was part of him. Sadly, he was right. He’s still up there, buried under hundreds of feet of debris.

The "Red Zone" was established, but it was controversial. People felt the government was overstepping. They wanted to check their summer homes. They wanted to hike. But David Johnston, a USGS volcanologist who was monitoring the peak from Coldwater II ridge, knew better. He was the one who famously radioed in, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" before the lateral blast hit his position. He didn't survive, but his data saved thousands of others who might have been in the path if the evacuation zones hadn't been enforced.

The Literal Seconds After 8:32 AM

When the 5.1 magnitude earthquake hit at 8:32 AM, the north face didn't just crumble; it liquefied. This was the largest landslide in recorded history.

💡 You might also like: The Highway 1 Landslide California Problem: Why This Road Keeps Disappearing

Basically, the pressure release was so sudden that the water inside the mountain flashed to steam instantly. It was a massive hydrothermal explosion. The lateral blast traveled at 670 miles per hour. It didn't just knock trees over. It stripped the bark off them. It sandblasted the landscape. If you were within eight miles of the crater, you weren't just hit by heat; you were hit by a wall of rock and ash that pulverized everything in its path.

Then came the lahars.

These are volcanic mudflows. Think of a river of wet concrete moving with the speed of a freight train. The heat melted the glaciers and snowfields instantly, sending millions of tons of water, mud, and boulders down the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers. It wiped out 200 homes and 27 bridges. It even choked the Columbia River, which is a massive shipping lane, stranding ocean-going vessels upstream in Portland.

The Ash Fall: When It Rained Gray

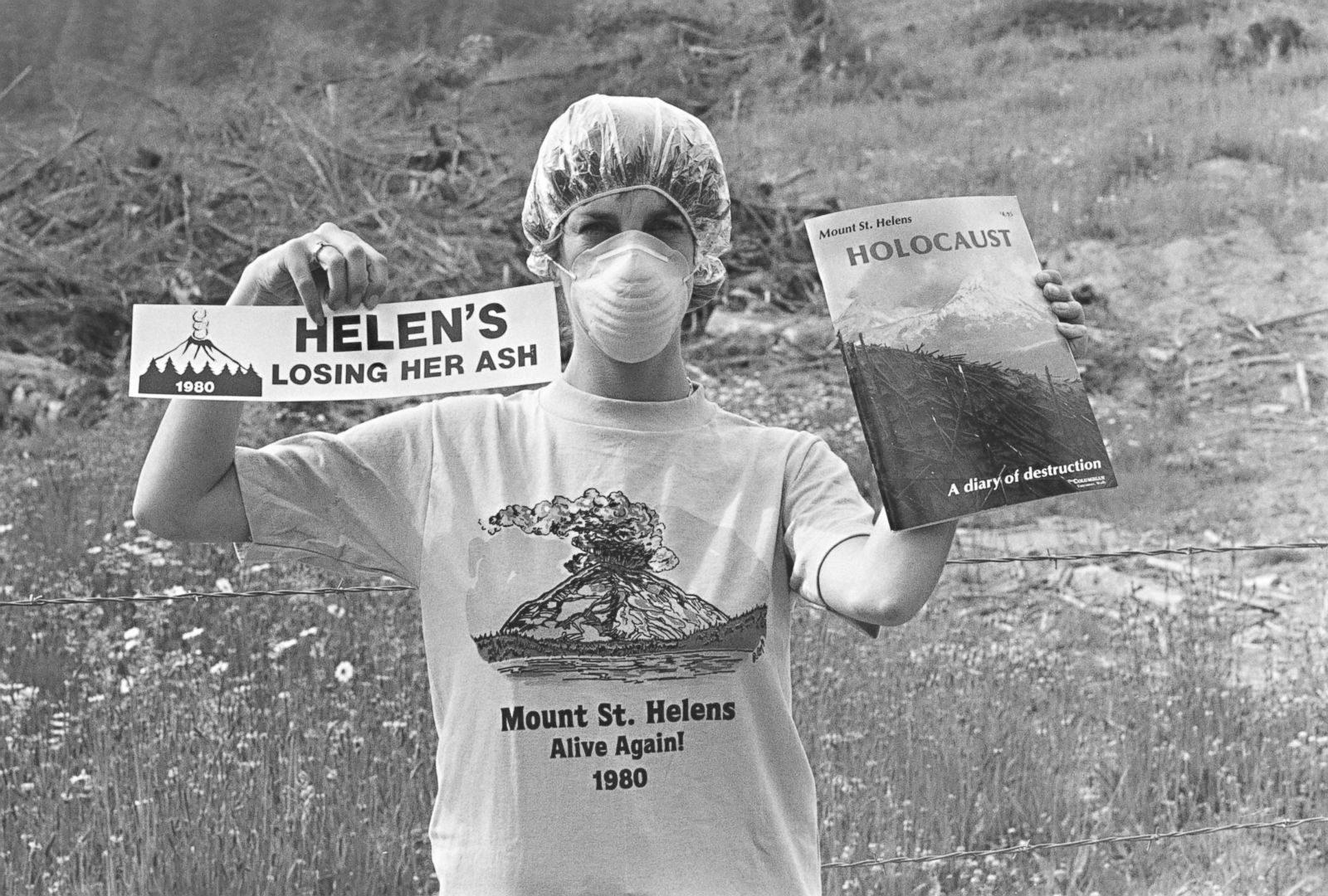

While the immediate blast zone was a moonscape, the rest of the Pacific Northwest was dealing with something else entirely. The ash plume rose 80,000 feet into the atmosphere in less than 15 minutes. It stayed up there for hours, blocking the sun so effectively that streetlights turned on in Yakima and Spokane at noon.

It wasn't like wood ash. It was ground-up rock—silica. It was abrasive. It destroyed car engines. It killed crops. It felt like the end of the world for people hundreds of miles away who had no idea if the mountain was still exploding or if they were breathing in something toxic.

The sheer volume of the Mount Saint Helens 1980 eruption is hard to wrap your head around. We're talking 0.1 cubic miles of tephra. That sounds small until you realize it's enough to bury a football field 150 miles deep.

The Misconception of "Recovery"

There’s this idea that the area is still a wasteland. Honestly? It's the opposite. The Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is a living laboratory. Biologists were shocked at how fast life came back.

- Pocket gophers survived in their burrows.

- Frogs and salamanders stayed cool in ice-covered lakes.

- Lupine—a hardy "pioneer plant"—was the first to break through the ash, fixing nitrogen into the soil so other plants could grow.

The forest isn't the same as it was, though. It’s a mosaic. Some areas are still desolate pumice plains, while others are lush with young alder and fir. It’s a reminder that nature doesn't "recover" to a previous state; it just adapts to the new one.

The landscape is still dangerous, too. The crater has a new lava dome growing inside it. Between 2004 and 2008, the volcano started oozing lava again, building up the floor of the crater. It’s not a dead rock; it’s a resting giant.

Why We Still Study the 1980 Eruption

Every major volcanic monitoring system in the world today—from Hawaii to the Andes—owes a debt to what we learned in Washington State. Before 1980, we didn't fully understand lateral blasts. We didn't have the same level of seismic monitoring. Now, the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory uses GPS to measure the mountain's "breathing" down to the millimeter.

We also learned about the human element. The "social" disaster was as big as the geological one. The tension between public safety and economic interest is a debate that still happens every time a natural disaster looms.

Visiting the Blast Zone Today

If you’re planning to head out there, don't just go to the Johnston Ridge Observatory (though the view is incredible). You need to see the different zones of destruction.

The Blowdown Forest

Drive along the Spirit Lake Highway. You’ll see hillsides where the trees are still lying like toothpicks, all pointing away from the crater. It’s been 45 years, and those logs are still there, silvered by the sun. They haven't rotted because the environment was so sterilized by the ash.

The Pumice Plain

This is the area directly in front of the crater. It’s haunting. It feels like you’ve been transported to Mars. Hiking across it gives you a sense of scale that photos just can't capture. You feel tiny. You feel temporary.

Ape Cave

On the south side of the mountain, things are totally different. This side didn't get blasted. You can walk through a massive lava tube formed during an eruption 2,000 years ago. It’s a weird contrast to the destruction on the north side.

What Most People Miss About the Statistics

We talk about the 57 people who died. It’s a tragedy. But it’s also a miracle the number wasn't in the thousands. If the eruption had happened on a Monday, when the logging crews were at full capacity in the woods, the death toll would have been staggering. Because it was a Sunday morning, the "work zones" were empty.

👉 See also: Paris Weather Right Now: What Most People Get Wrong About January in the City of Light

Also, the height of the mountain changed forever. It dropped from 9,677 feet to 8,363 feet. It lost 1,314 feet of elevation in a single morning. That’s about the height of the Empire State Building just... gone.

Practical Steps for History and Nature Buffs

If you want to truly understand the impact of Mount Saint Helens 1980, don't just read the Wikipedia page.

First, check the current status of the Johnston Ridge Observatory. It often faces closures due to landslides on the access road—nature is still reclaiming that highway. If it's closed, the Science and Learning Center at Coldwater is your best bet for a high-elevation view.

Second, look up the "Mount St. Helens Institute." They offer guided climbs to the rim. It’s a non-technical hike (meaning you don't need ropes), but it is a grueling 10-hour slog through volcanic scree. Standing on the rim and looking down into the crater where a glacier is currently wrapped around a steaming lava dome is a perspective you won't get anywhere else.

Third, respect the permit system. The blast zone is still a protected research area. Don't go off-trail in the restricted zones. Scientists are still tracking how long-term succession works, and a single pair of hiking boots can mess up a decades-long study on moss or insect return.

Lastly, keep an eye on the seismograph. The USGS posts real-time data online. Seeing the "heartbeat" of the mountain reminds you that the 1980 event wasn't a one-off. It was just the latest chapter in a story that’s been going on for 40,000 years.

The reality of the 1980 eruption is that it changed how we live in the Pacific Northwest. We now have evacuation routes. We have ash-management plans. We have a healthy respect for the Cascades. We realized that these mountains aren't just scenery; they're the surface of a very active, very powerful planet.

✨ Don't miss: Lake Francis State Park: Why This Northern NH Escape Beats the White Mountains

Actionable Next Steps:

- Check the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory for real-time seismic updates before planning a trip.

- Secure a climbing permit via the Mount St. Helens Institute if you intend to summit; they sell out months in advance during the summer season.

- Visit the Hoffstadt Bluffs Visitor Center for a clear view of the mudflow paths that permanently altered the region's river systems.

- Prepare for "gray days" even now—if you're hiking in the blast zone, carry a buff or mask, as high winds can still kick up original 1980 ash that can irritate your lungs.