It was a Sunday. May 18, 1980. Most people in Washington state were just waking up, pouring coffee, or thinking about heading to church. Then the ground shook. But it wasn't just a shake—it was a total structural failure of a mountain. Honestly, when we talk about the Mount St. Helens eruption 1980, we usually focus on the smoke and the ash, but the real story is the sheer, terrifying physics of a mountain falling apart.

David Johnston, a volcanologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, was stationed on a ridge about six miles away. He was the one who shouted "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" into his radio. He didn't survive. That ridge is now named after him, a grim reminder that even the experts were stunned by the lateral nature of the blast. Everyone expected the volcano to blow upward like a champagne cork. Instead, it blew sideways.

The Bulge That Nobody Could Stop

For weeks leading up to the disaster, the north face of the mountain had been growing. It was weird. It was called "the bulge," and it was expanding by about five feet per day. Imagine a mountain just inflating like a balloon. Geologists knew something was wrong, but there was a massive debate about how much of an area to evacuate. Local residents and lodge owners, like the legendary Harry R. Truman, famously refused to leave. Truman lived at Spirit Lake and became a bit of a folk hero for his stubbornness, claiming the mountain wouldn't hurt him. He, along with his 16 cats, was buried under hundreds of feet of debris within seconds.

The 5.1 magnitude earthquake at 8:32 a.m. was the trigger. It caused the entire north face—the bulge—to slide away. This was the largest debris avalanche in recorded history. With the weight of the rock gone, the superheated water and magma inside the volcano suddenly turned to steam. It was basically a giant pressure cooker losing its lid.

The Lateral Blast: A 300-MPH Hurricane of Fire

Once the mountain opened up, the "lateral blast" happened. This wasn't just lava. It was a pyroclastic surge—a mix of hot gas, ash, and rock fragments. It traveled at speeds over 300 miles per hour. It didn't care about valleys or ridges; it just leveled everything in a 230-square-mile area.

If you look at the photos from the "Inner Blast Zone," you see thousands of Douglas fir trees, some hundreds of years old, snapped like toothpicks. They weren't just knocked down; they were stripped of their bark and needles by the sheer friction of the ash. It looked like a forest of gray matchsticks. Most of them were blown flat in a radial pattern, pointing directly away from the crater.

The heat was intense. In some spots, it reached 660 degrees Fahrenheit. People miles away felt the heat on their skin before they even heard the sound. Interestingly, there was a "quiet zone" around the mountain because of the way sound waves traveled through the atmosphere. People in Portland, relatively close by, heard nothing. People in British Columbia, hundreds of miles away, thought they heard gunfire or explosions.

Mud, Ash, and Total Darkness

While the blast was the killer, the "lahars" were the destroyers. A lahar is basically a volcanic mudflow. When the heat hit the glaciers and snow on the mountain, it melted instantly. This water mixed with ash and rock to create a slurry with the consistency of wet concrete. It roared down the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers. It carried away houses, logging trucks, and entire bridges.

✨ Don't miss: Reese Manchaca Found: What Really Happened in the Hill Country

Then came the ash.

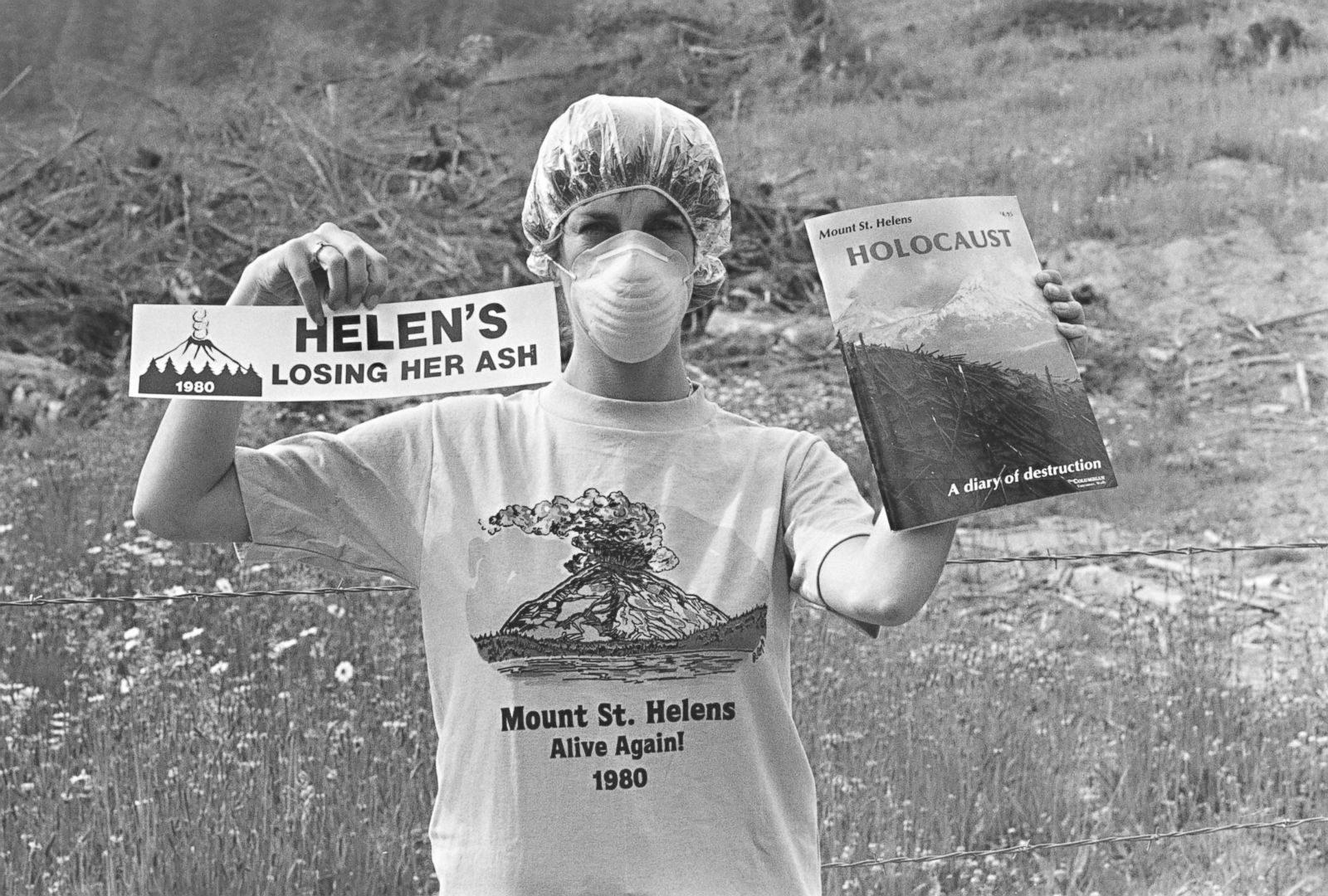

The plume went 80,000 feet into the air in less than 15 minutes. It turned noon into midnight in places like Yakima and Ritzville. People were terrified. They wore surgical masks to breathe. Streetlights turned on. Cars stalled because the ash was so fine it clogged air filters and acted like sandpaper on engine parts. It wasn't like wood ash; it was pulverized rock. It was heavy, it was abrasive, and it didn't dissolve in water.

Why This Event Changed Science Forever

Before the Mount St. Helens eruption 1980, we didn't really understand lateral blasts. We thought volcanoes were mostly vertical. This event forced the USGS and volcanologists worldwide to rethink their monitoring systems. We started looking at "sector collapses" as a primary threat for other peaks like Mt. Rainier or Mt. Hood.

It also gave us a front-row seat to how life returns after a total wipeout. Biologists thought the blast zone would be a moonscape for a century. They were wrong. Within years, "pioneer species" started popping up. Gophers survived in their burrows. Lupine flowers started blooming in the ash because they could "fix" nitrogen into the soil. It was a lesson in ecological resilience.

Misconceptions and Cold Hard Facts

A lot of people think the eruption happened because of a lack of warning. That's not true. The USGS had been sounding the alarm for months. The real issue was the "Red Zone" boundaries. Lawmakers were under pressure to keep areas open for logging and tourism. If the eruption had happened on a Monday, when hundreds of loggers were scheduled to be in the woods, the death toll would have been in the thousands instead of 57.

- Death Toll: 57 people (including David Johnston and Harry Truman).

- Economic Impact: Roughly $1.1 billion in 1980 dollars.

- Ash Volume: 540 million tons spread over 22,000 square miles.

- Elevation Loss: The mountain lost 1,314 feet of its summit.

The mountain is still active. It built a new lava dome inside the crater throughout the 80s and again in the mid-2000s. It’s breathing. It’s quiet right now, but it's one of the most closely monitored volcanoes on the planet.

How to Visit Mount St. Helens Today

If you're planning a trip to see the site, don't just go to the gift shops. You need to see the scale of it.

Start at the Johnston Ridge Observatory. It’s literally right in the path of where the blast happened. You can see the crater, the lava dome, and the "pumice plain." It’s haunting.

Check out the Trail of Two Forests. This is a great spot to see how old lava flows from thousands of years ago molded around trees, creating "tree casts" or vertical caves.

Drive to Windy Ridge. This gives you a view of Spirit Lake. You’ll notice thousands of logs still floating on the surface. They’ve been there since 1980. They don't sink because they're so tightly packed, and the cold water preserves them.

Monitor the USGS updates. Before you go, check the Volcano Hazards Program website. It’s unlikely to blow while you're there, but it's good practice to know the current alert level.

The Mount St. Helens eruption 1980 wasn't just a disaster; it was a pivot point in history. It showed us that the Earth is way more dynamic—and way more dangerous—than we usually like to admit.

Practical Steps for Your Trip

- Check the Season: Most high-elevation roads like the one to Johnston Ridge are closed in winter due to heavy snow. Aim for July through September.

- Pack a Mask: It sounds weird, but if you're hiking in the ashier parts on a windy day, the dust is still there. It can irritate your lungs.

- Respect the Boundaries: The "Research Area" is restricted. Stay on the marked trails to allow the ecosystem to continue its recovery.

- Visit the Pine Creek Information Station: It's less crowded than the main center and offers a different perspective on the mudflows.

- Get a Permit: If you actually want to climb to the rim (it’s a strenuous hike, not a walk), you need a permit from the Mount St. Helens Institute. They sell out months in advance.