If you’ve ever fallen down a YouTube rabbit hole looking for the definitive Mount St. Helens eruption video, you’ve probably noticed something weird. Most of the "footage" from the exact moment the mountain collapsed is actually a series of still photos stitched together.

It’s a strange historical gap. We have crisp video of the moon landing from eleven years earlier, yet the most famous volcanic event in American history is mostly documented through grainy stop-motion sequences and harrowing audio tapes. Honestly, it’s kinda frustrating if you’re looking for a smooth, high-definition 4K shot of the North Face falling away.

But that’s because nobody was standing there with a modern camcorder. In 1980, "video" meant heavy, bulky ENG cameras used by news crews, or 16mm film that was expensive and difficult to operate under pressure. Most people had 35mm SLRs.

When the mountain finally went at 8:32 a.m. on May 18, the people closest to it weren't thinking about framing a shot. They were thinking about not dying.

The Gary Rosenquist Sequence: The "Video" That Isn't

The most famous Mount St. Helens eruption video isn't actually a video at all. It’s a series of 22 still photographs taken by Gary Rosenquist. He was camping at Bear Meadow, about 11 miles northeast of the peak.

You’ve definitely seen this. It’s the sequence where the entire side of the mountain seems to turn into a liquid and slide downward. Because Rosenquist was manually advancing his film—basically clicking as fast as he could—the intervals between shots aren't even. Some gaps are 1.2 seconds, others are nearly 3 seconds because of the sheer "holy crap" factor of what he was witnessing.

Geologists later used these frames to calculate that the landslide was moving at speeds over 150 mph. When you see this "video" on TV today, it’s usually been "morphed" by AI or digital interpolation to make it look fluid. In the original 1980 reality? It was just a man with a Minolta camera trying to remember to breathe while a mountain disintegrated in front of him.

Dave Crockett’s Terrifying First-Person Record

If you want actual, moving film with sound, you have to look at the Dave Crockett footage. This is the real deal.

Crockett was a photographer for KOMO-TV. He got caught in the path of the ash cloud and survived by a literal miracle. His Mount St. Helens eruption video is some of the most haunting media ever recorded. It’s not a wide shot of a volcano; it’s a black screen.

As the ash choked out the sun, it became pitch black in the middle of the morning. You can hear him talking to himself—essentially recording his last will and testament—as ash falls like heavy, hot snow on his car. He talks about how it "burns to breathe."

"Dear God... whoever finds this... I'm walking toward the only light I can see. I can hear the mountain behind me rumbling."

He eventually made it out, but that footage serves as a brutal reminder that a "cool volcano video" was actually a death trap for 57 people.

📖 Related: Why the Coolest Castles in the World Still Feel Like Magic

The Stoffel Flight: A View From Above

Geologists Keith and Dorothy Stoffel were actually flying over the crater in a Cessna at the exact moment of the eruption. Talk about bad timing (or incredible timing, depending on how you look at it).

Keith Stoffel managed to capture photos of the initial collapse from the air. Their pilot, Bruce Judson, had to dive the plane to gain enough airspeed to outrun the rising ash column. Imagine looking out a small plane window and seeing the ground beneath you simply vanish into a cloud of debris. They were some of the only people to see the "bulge" fail from a vertical perspective.

Why isn't there better footage?

- The Blast was a Lateral Surprise: Everyone expected the volcano to go up, like a champagne cork. Instead, it blew sideways (a lateral blast). This meant people who thought they were in "safe" zones were suddenly in the direct line of fire.

- Equipment Limitations: Handheld video cameras in 1980 required separate VCR decks or heavy batteries. You didn't just "whip out your phone."

- The Ash: Volcanic ash is basically pulverized rock. It destroys engines and clogs camera internals almost instantly.

The USGS "Scientific" Video

There is some legitimate 16mm film footage taken by USGS scientist Don Swanson. However, he started filming about an hour after the initial blast. His Mount St. Helens eruption video shows the massive ash plume—which eventually reached 16 miles high—and the pyroclastic flows hugging the ground.

While it lacks the "instant of collapse" drama of the Rosenquist photos, Swanson’s footage is what scientists actually use to study how the volcano behaved throughout the rest of that Sunday. It shows the sheer scale of the energy being released—roughly equivalent to 1,600 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs.

Robert Landsburg’s Ultimate Sacrifice

We can't talk about the visual record of this day without mentioning Robert Landsburg. He was a freelance photographer who was even closer than Rosenquist.

When he realized the ash cloud was going to overtake him and there was no way to outrun it, he did something incredibly deliberate. He took his final photos, rewound the film, put the camera in its case, put the case in his backpack, and then laid his body on top of the backpack.

He used his own body as a shield to protect the film from the heat and debris. His body was found 17 days later. The film survived. The photos he took are some of the most terrifyingly close images of the wall of ash ever captured.

What to Look For When You Search

If you're looking for the most "authentic" experience of the eruption today, don't just look for a single video. Look for the "Minute by Minute" documentaries or the USGS archives.

Specifically, look for:

- The Rosenquist Sequence (Morphed): Best for seeing the landslide.

- The Dave Crockett Audio/Video: Best for feeling the terror of the ash fall.

- The 2004-2008 Time-lapses: These are high-quality modern videos of the dome growing back, which provide a "sequel" to the 1980 disaster.

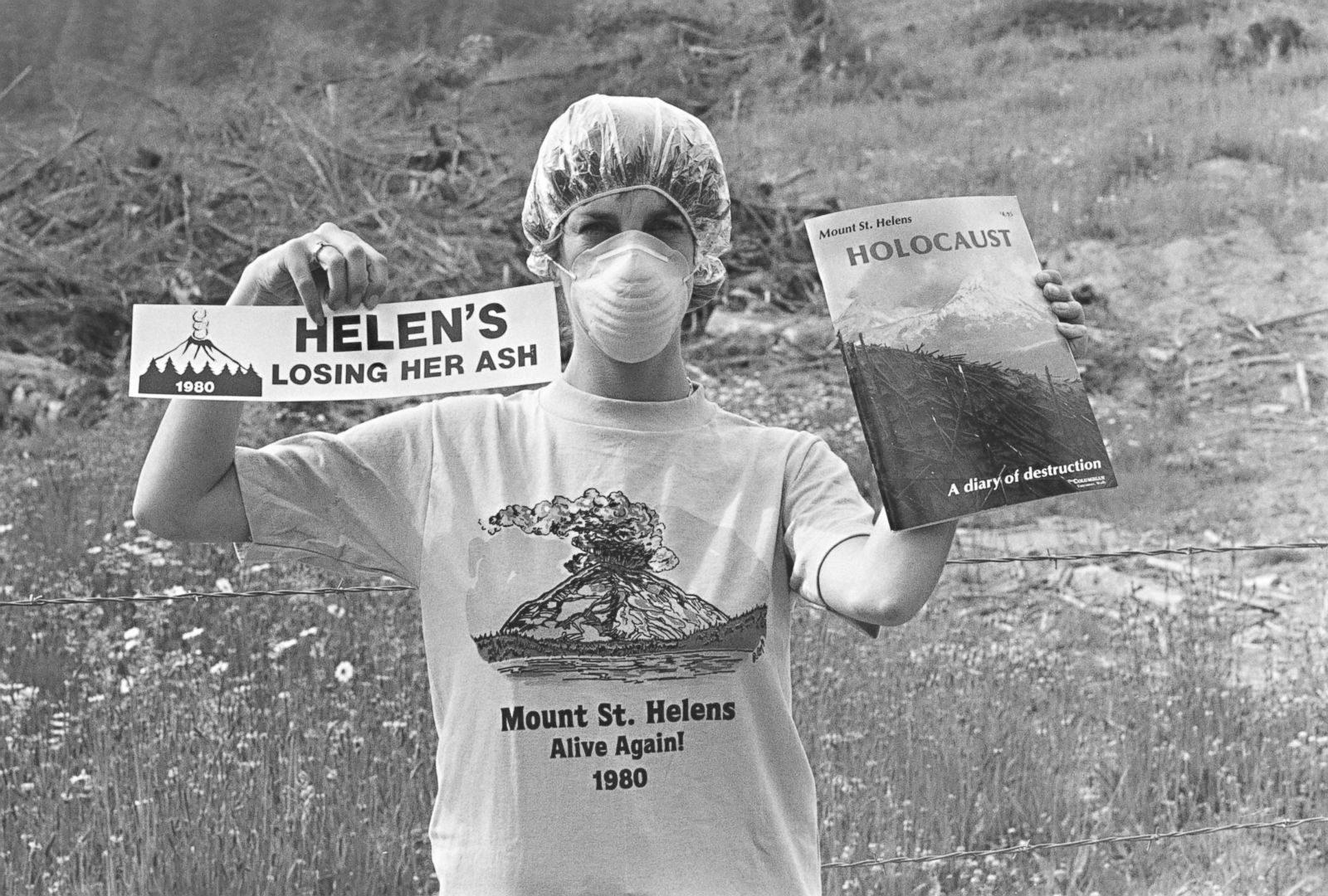

Basically, the 1980 eruption was a "pre-digital" disaster. We see it through the eyes of people who were using mechanical tools to capture a geological nightmare.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

If you want to see the impact of the eruption yourself, the best thing you can do is visit the Johnston Ridge Observatory (when it's open—check for road closures as they've had recent landslides). Standing where David Johnston stood when he shouted his final words, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!", provides a perspective that no Mount St. Helens eruption video can ever replicate. You can also browse the digital archives at the Mount St. Helens Institute to see high-resolution scans of the Landsburg and Rosenquist reels.