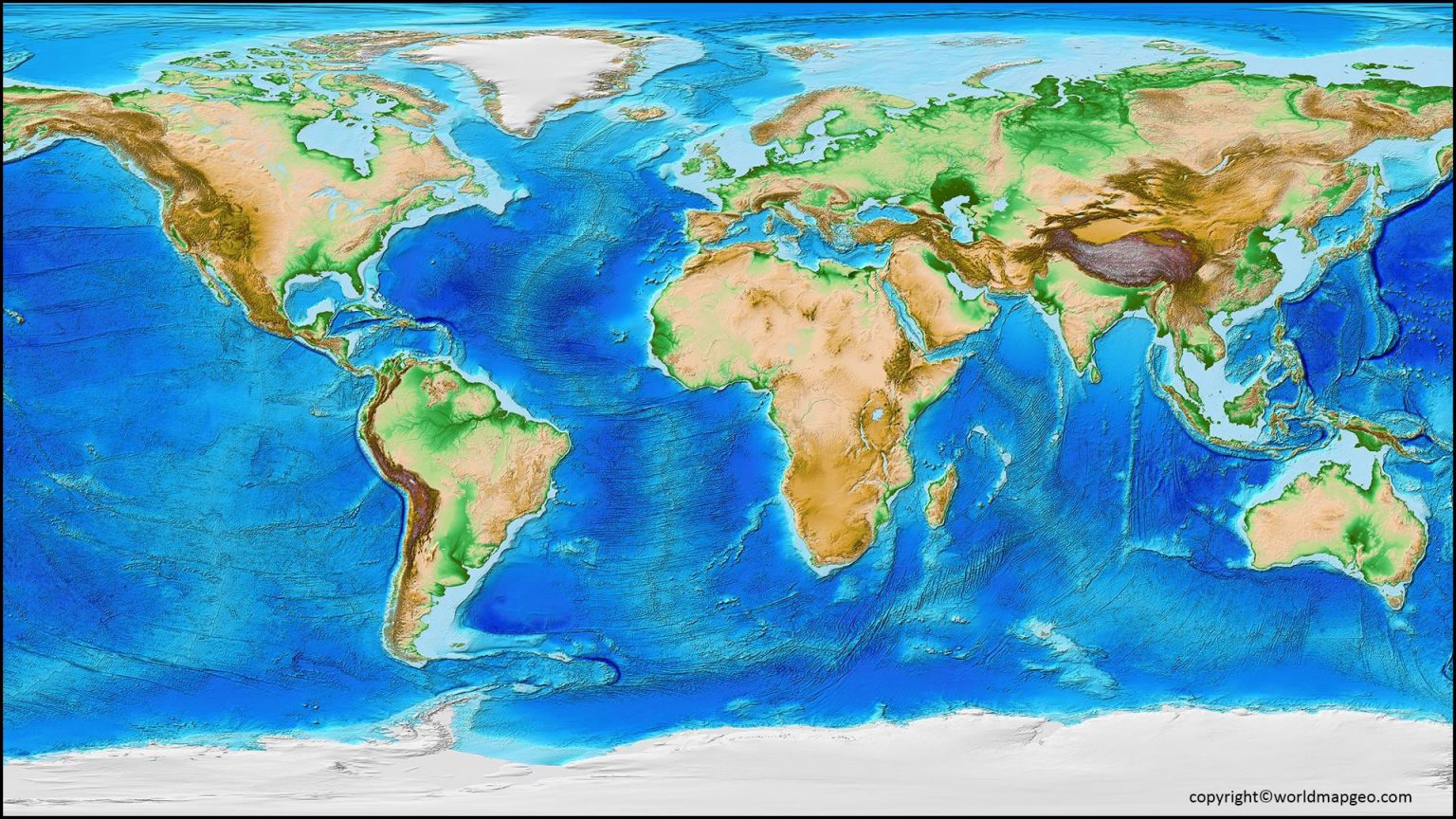

You’ve seen them since third grade. Those jagged brown lines zig-zagging across a schoolroom poster. Most of us think we know the mountain ranges map of the world by heart, but here’s the thing: geography is kind of messy. If you look at a standard physical map, you see the Rockies, the Andes, and the Himalayas. They look like isolated incidents. In reality, these massive stone spines are interconnected by tectonic stories that began hundreds of millions of years ago, and they're still moving.

Mountains aren't just scenery. They’re the world’s water towers. They’re weather makers. Honestly, without the specific layout of the mountain ranges map of the world we have today, the Amazon would be a desert and the Gobi might be a jungle. It’s all connected.

The Ring of Fire and the Undersea Giants

Most people forget that the most impressive mountain range isn't even on land. If you really want to understand a mountain ranges map of the world, you have to look underwater. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is the longest mountain chain on the planet. It stretches for about 40,000 miles. It’s basically a massive seam where the earth is pulling itself apart.

Then you have the Ring of Fire. This isn't just a Johnny Cash song; it’s a horse-shoe shaped belt of seismic activity circling the Pacific Ocean. This is where the heavy lifting happens. The Andes are the star of the show here. They run 4,300 miles down the western edge of South America. Because they were formed by subduction—where one plate slides under another—they are incredibly steep and pack more than 50 peaks that soar over 20,000 feet.

Compare that to the Appalachians in the eastern United States. They look like rolling hills on a modern mountain ranges map of the world, right? But 300 million years ago, they were likely as tall and jagged as the Alps. Time is a brutal sculptor. Wind and ice have spent eons grinding them down. When you look at a map, you aren't just looking at height; you're looking at age.

Why the Himalayas Are a Special Case

The Himalayas are the "young" celebrities of the geography world. About 50 million years ago, the Indian Plate decided it wanted to crash into the Eurasian Plate. It didn't just bump into it. It’s still shoving into it at a rate of about two inches per year.

This collision is why the Himalayas are home to all fourteen of the world’s "eight-thousanders"—peaks that exceed 8,000 meters. Mount Everest and K2 aren't just tall; they are growing. Well, Everest is growing about 4 millimeters a year, though earthquakes can occasionally knock a bit of that height back down.

The Tibetan Plateau: The Third Pole

North of the main Himalayan spine lies the Tibetan Plateau. Scientists call this the "Third Pole" because it holds the largest reserve of fresh water outside the Arctic and Antarctic. On a mountain ranges map of the world, this looks like a big, high-altitude blob. In real life, it’s the source of the Yangtze, the Yellow River, the Mekong, and the Ganges. If those mountains weren't there to catch the monsoon rains, billions of people would have no water. It's that simple.

The Great Divide: North America’s Spine

When you zoom into North America, the Rockies dominate the mountain ranges map of the world. They stretch from British Columbia down to New Mexico. But they aren't one single line. They’re a collection of over 100 separate ranges.

The Continental Divide is the invisible line running through these peaks. It’s a trip to think about: a raindrop falling an inch to the west ends up in the Pacific. An inch to the east? It’s headed for the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico.

- The Sierra Nevada: These are "fault-block" mountains. Basically, a massive chunk of the earth's crust tilted up. It’s why the eastern side is a sheer drop and the western side is a long, gentle slope.

- The Cascades: These are volcanic. Mount St. Helens, Rainier, Hood. They exist because the ocean floor is melting underneath the continent.

- The Brooks Range: Way up in Alaska. It’s desolate, brutal, and serves as a northern wall that keeps the Arctic chill from moving south too fast.

The European Paradox: The Alps and Beyond

Europe’s mountains are weirdly compact. The Alps are the most famous, obviously. They’ve defined European history, acting as a barrier that kept the Romans and the "barbarians" apart for centuries. But look further east on a mountain ranges map of the world.

The Caucasus Mountains, sitting between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, are actually where you’ll find Europe’s highest peak, Mount Elbrus. People always argue about whether the Caucasus are in Europe or Asia. Geographically, they’re the border. They’re rugged, politically complex, and much more "wild" than the ski resorts of Switzerland.

Then you have the Urals. They’re the official line between Europe and Asia. They aren't particularly tall—most of them are under 6,000 feet—but they’ve been there for 250 million years. They are the "old guard" of the mountain world.

🔗 Read more: Other Words for Sand: What Most Geologists (and Beachgoers) Get Wrong

Africa and the Great Rift

Africa’s mountain ranges map of the world is unique because it isn't dominated by one long chain like the Andes. Instead, you have massive "islands" of rock.

Kilimanjaro is the classic example. It’s a stratovolcano. It stands alone. You have the Atlas Mountains in the north, which are basically the African version of the Alps—formed by the same tectonic movements. But the real story in Africa is the East African Rift. The continent is literally tearing itself apart. This creates "horst and graben" topography—valleys dropping down and mountains pushing up. It’s why you see these deep, long lakes like Lake Tanganyika bordered by massive cliffs.

What a Map Doesn't Tell You

Standard maps are 2D, which is a problem. They don't show the "rain shadow" effect. This is one of the most important things to understand about the mountain ranges map of the world.

When moist air hits a mountain, it’s forced upward. It cools, it rains, and the "windward" side becomes a lush forest. By the time the air gets over the top, it’s bone dry. This is why the Atacama Desert exists right next to the Andes. It's why eastern Washington state is a desert while Seattle is a rainforest. Mountains are the ultimate gatekeepers of life.

Practical Steps for Geographic Literacy

If you’re trying to master the mountain ranges map of the world for a project, travel planning, or just to sound smart at dinner, stop looking at flat maps.

- Use 3D Visualization: Tools like Google Earth or "Fatmap" give you a sense of scale that a paper map never can. Look at the "vertical exaggeration" settings to see how ranges actually interact with weather patterns.

- Learn the "Orogeny" Names: If you want to understand why mountains look the way they do, look up the Laramide orogeny (Rockies) or the Alpine orogeny. It explains the "vibe" of the rock—whether it's jagged and young or rounded and old.

- Check the Snowlines: When studying a map, look at the latitude. A 10,000-foot mountain in Alaska is a glacier-covered monster. A 10,000-foot mountain in the African tropics might just be a pleasant hike.

- Follow the Water: Trace the world's major rivers back to their source. You’ll find that the mountain ranges map of the world is essentially a map of where every civilization began.

Understanding these ranges isn't just about memorizing names. It’s about seeing the skeleton of the planet. The Earth is a living, moving thing, and these mountains are the scars and wrinkles that tell its story. Next time you see a range on a map, don't just see a line; see a collision that's been happening for millions of years and hasn't finished yet.