You’re standing in the baking aisle, looking at those tiny neon plastic squeeze bottles. You want pink frosting for a birthday cake, but the back of the box looks like a chemistry lab manual. Red 40. Red 3. Erythrosine. If you’ve ever felt a weird twinge of guilt dropping those synthetic dyes into a bowl of organic flour, you aren't alone. It's kinda funny how we obsess over "clean labels" but then ignore the neon pink sludge in our cupcakes.

Switching to natural pink food dye isn't just a trend for people who shop exclusively at high-end co-ops. It's actually a massive shift in how we think about food safety and aesthetics. But here is the thing: most people mess it up. They think "natural" means it’s going to behave exactly like the lab-made stuff. It won't. If you try to bake beet juice into a high-pH vanilla cake, you aren't getting pink. You’re getting a depressing, muddy brown.

The Chemistry of Why Pink is Hard

Let’s get real about the science. Synthetic dyes are basically bulletproof. You can boil them, freeze them, or leave them in the sun, and they stay vibrant. Natural pigments? They’re sensitive. They’re moody. Most natural pinks come from a class of pigments called anthocyanins or betalains.

Anthocyanins are found in things like hibiscus and berries. They are basically nature’s pH strips. If your batter is acidic (like a lemon cake), the color stays a beautiful, sharp pink. If you add a bunch of baking soda—which is alkaline—the color shifts to a weird purple or even a swampy blue-green. Honestly, it’s a science experiment you didn't ask for.

Then you have betalains, which are what make beets so aggressively red-pink. Beets are the heavy hitters of the natural pink food dye world because they don't care as much about pH. But they hate heat. If you put beet-based dye in a cookie that bakes for 15 minutes, the pigment often degrades. You end up with a "toasted" look rather than a vibrant rose.

The Beetle in the Room: Carmine

We have to talk about the bug. If you look at a "natural" pink grapefruit juice or a strawberry yogurt, you might see "Carmine" or "Cochineal Extract" on the label.

✨ Don't miss: Red Lake Powwow 2025: What You Actually Need to Know Before Heading to the Rez

This isn't plant-based.

It comes from the crushed bodies of the female Dactylopius coccus insect, a scale bug that lives on cacti in Peru and the Canary Islands. It produces a stunning, heat-stable, light-stable pink and red. It’s been used for centuries—even the British "Redcoats" used it for their uniforms. While it is technically a natural pink food dye, it isn't vegan, and it’s a dealbreaker for many. Plus, the FDA requires it to be explicitly labeled because some people have severe allergic reactions to the insect proteins.

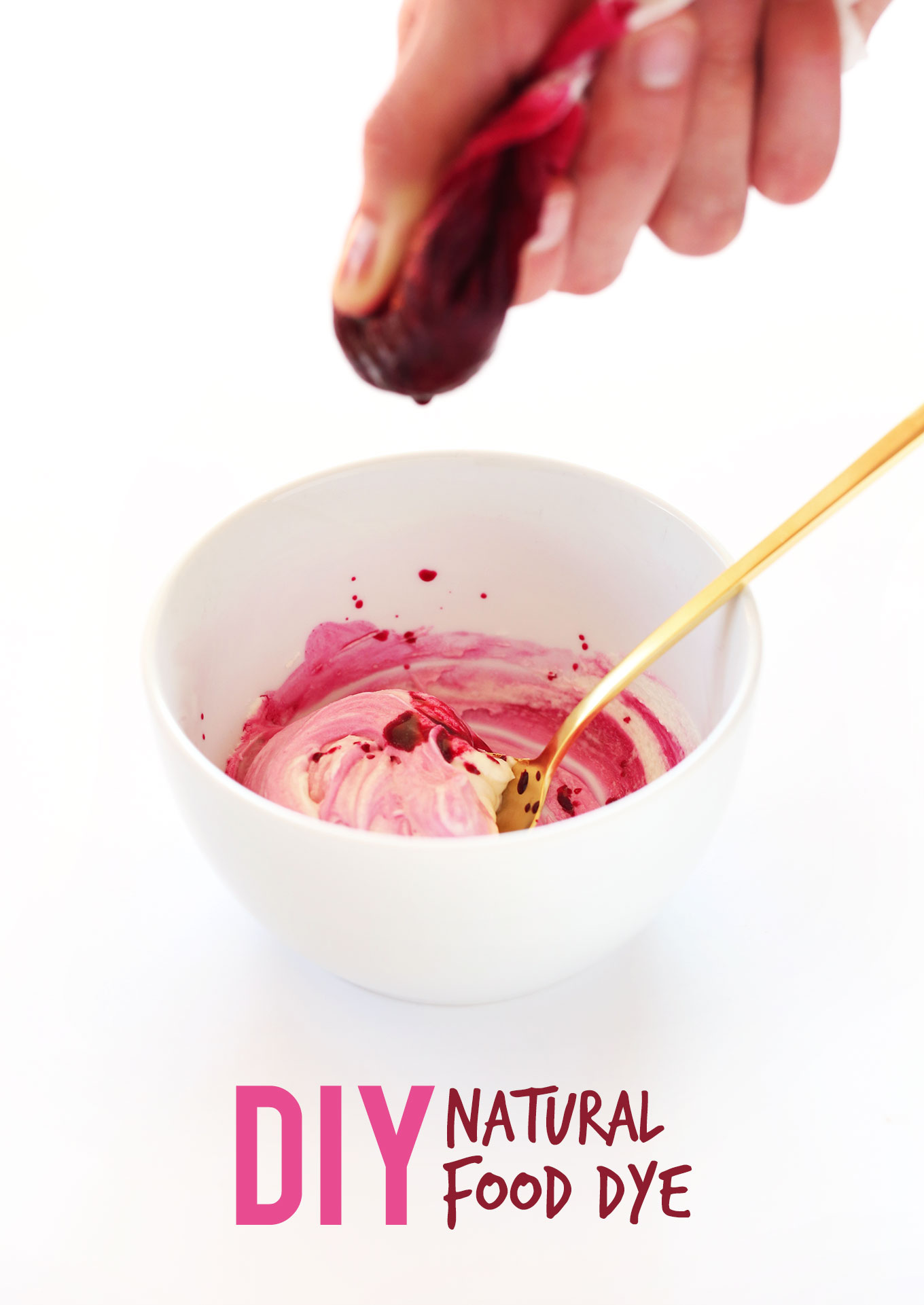

Beet Powder: The Reliable Workhorse

If you’re doing this at home, beet powder is basically your best friend. It’s concentrated. It’s accessible.

I’ve seen people try to use raw beet juice in frosting, and it’s a disaster. Why? Because of the water content. If you add enough juice to get a deep pink, your buttercream will break and turn into a soupy mess. Powder is the way to go.

- Pro Tip: Look for "freeze-dried" beet powder. The color is much more vibrant than air-dried versions.

- The Flavor Factor: Beets taste like dirt. Well, "earthy" if we’re being polite. To mask that, you need a strong counter-flavor like vanilla bean or almond extract.

- Use Case: Best for raw applications like frostings, glazes, smoothies, or raw "cheesecakes."

Dragon Fruit: The Neon Aesthetic

If you want that "Instagram pink"—that bright, almost electric fuchsia—you need Pitaya (Dragon Fruit). Specifically the red-fleshed variety.

Dried dragon fruit powder provides a color that beet powder simply cannot touch. It is shockingly bright. However, it is also incredibly sensitive to heat. It’s perfect for coloring a pitaya bowl or a cold glaze, but if you put it in a 350-degree oven, don't expect it to look the same when it comes out.

Hibiscus: The Sophisticated Pink

Hibiscus flowers aren't just for tea. They contain incredibly potent anthocyanins.

If you simmer dried hibiscus flowers into a concentrated syrup, you get a deep, ruby-pink liquid that is perfect for cocktails or soaking cakes. It has a sharp, tart flavor—kinda like cranberry. This acidity actually helps stabilize the pink color.

🔗 Read more: Why a World Map Without Names is Actually More Useful Than You Think

But remember the pH rule. If you mix hibiscus syrup into a batter with a lot of baking soda, it’s going to turn gray. You’ve been warned.

Why the Industry is Scrambling

It isn't just home bakers. Big Food is panicking about natural pink food dye.

Companies like Nestle and Mars have been trying to phase out synthetics for years. The problem is scale and cost. Red 40 is dirt cheap. Growing millions of acres of beets or harvesting bugs in Peru is expensive.

There is also the "fading" issue. Have you ever noticed that some organic fruit snacks look kind of... beige? That’s because natural dyes fade when exposed to light on a grocery store shelf. Manufacturers are now looking into things like Purple Sweet Potato and Black Carrot. These sounds like they’d make things purple, but when diluted and adjusted for pH, they produce a very stable, beautiful pink.

The Problem With Strawberry and Raspberry

You’d think strawberries would be the obvious choice for pink dye.

They aren't.

Strawberries oxidize almost immediately. Once they hit the air and light, they turn a brownish-pink. Unless you are using a massive amount of freeze-dried strawberry powder, it’s hard to get a consistent color. Raspberries are a bit better, but the seeds are a nightmare to deal with, and the cost per ounce of pigment is astronomical compared to a humble beet.

How to Actually Use Natural Pink Food Dye Without Ruining Your Food

If you want to succeed with these dyes, you have to change your workflow.

📖 Related: Why Reaction to an Awful Pun NYT Still Makes People Lose Their Minds Every Morning

First, stop thinking about "drops." Natural dyes are often powders or thick pastes. You need to whisk them into a small amount of liquid first to avoid clumps. If you're making a cake, consider using an "acid-wash" technique. Adding a bit of lemon juice or cream of tartar to your batter can lower the pH enough to keep those pink pigments from shifting toward blue or gray.

Second, temper your expectations on "Neon." Natural pinks are usually softer. They look like the earth they came from. They have depth and soul, but they aren't going to glow in the dark.

Third, watch the temperature. For baked goods, try "low and slow" baking if the recipe allows. Lowering the oven temperature by 25 degrees and baking for a few minutes longer can sometimes preserve the delicate betalains in beet powder.

Practical Next Steps for Your Kitchen

Ready to ditch the Red 40? Here is how to actually start.

1. Buy the right kit. Don't just buy "food coloring." Buy a small bag of freeze-dried dragon fruit powder and a bag of high-quality beet powder. Brands like Suncore Foods or even local health food store bulk bins are great starting points.

2. Test your pH. If you’re a serious baker, keep a little bottle of lemon juice nearby. Before you commit to a full batch of frosting, mix a tiny bit of your natural dye with the frosting. If it looks "off," add a drop of lemon juice. If the color brightens up, you know you have a pH issue.

3. Embrace the flavor. Don't try to hide the fact that you're using real plants. A hibiscus-pink glaze should taste a little tart. A strawberry-powder frosting should taste like berries. The biggest mistake is trying to make natural food taste like "fake" food.

4. Storage matters. Keep your natural dye powders in the freezer or a very dark, cool cupboard. Light and heat are the enemies of natural pigments. If your beet powder has been sitting on a sunny shelf for six months, it’s going to be a dull, brown shadow of its former self.

Natural pink food dye is a bit of a diva. It's demanding, it's sensitive, and it’s expensive. But the results feel more authentic and, honestly, a lot more impressive once you master the nuances of the chemistry involved.