New York wasn't always a glass-and-steel playground. Honestly, if you look at New York City 1800s photos, you'll realize the place was a muddy, chaotic, smells-like-horse-manure mess. It was vibrant. It was terrifying.

Photography was a brand-new miracle back then. Louis Daguerre only revealed his process in 1839. Before that? Nothing but sketches and memory. But by the middle of the century, photographers like Mathew Brady and Anthony & Co. were lugging heavy glass plates and toxic chemicals around Manhattan to capture a city that was growing faster than it could breathe.

You see the grime. You see the goats.

Wait, goats? Yeah. Central Park wasn't always a manicured lawn; it was a rocky outcrop where squatters lived in shanties. When you dig into these archives, you aren't just looking at old pictures. You're looking at a blueprint for the modern world, stained with coal dust and ambition.

🔗 Read more: Cool Things to Do in Los Angeles: What Most People Get Wrong

The daguerreotype era and why everything looks so empty

Have you ever noticed how the earliest New York City 1800s photos look like ghost towns? It’s kind of eerie. You’ll see a shot of Broadway from 1840, and the street is basically a desert.

The tech was slow. Really slow.

Exposure times could last several minutes. If a carriage rattled by or a person walked across the frame, they simply vanished. They didn't move slow enough to register on the silver-plated copper. Only the buildings stayed still. The city’s pulse was too fast for the cameras of the time to catch. It’s a paradox: the busier the street was, the emptier the photo looked.

By the 1850s, things changed. The "wet plate" collodion process made it possible to capture movement slightly better. We started seeing the people. We started seeing the chaos.

What the Bowery actually looked like

Forget the polished tourist version of Manhattan. The 1800s were brutal.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, the Bowery was the center of the universe for anyone who wasn't a Rockefeller. While the rich were uptown building châteaus on Fifth Avenue, the rest of the world was squeezed into the Lower East Side.

Jacob Riis is the name you need to know here. He wasn't just a photographer; he was a reformer. His book, How the Other Half Lives, used photography as a weapon. He used a primitive flash—basically frying pan of magnesium powder that literally exploded—to light up the dark corners of tenements.

Those photos are hard to look at.

Twelve people in a room the size of a closet. Kids sleeping on "stale-beer" cellar floors. This wasn't the "Gilded Age" for them; it was just a struggle to not die of cholera. Riis proved that photography could do more than just make pretty portraits. It could force the government to change building codes. It actually worked.

The infrastructure obsession

New Yorkers have always loved building big stuff.

Take the Brooklyn Bridge. Construction started in 1869 and took fourteen years. The photos of the caissons—those massive wooden boxes sunk into the riverbed—are mind-blowing. Men worked down there in compressed air, getting "the bends" before anyone really knew what that was.

✨ Don't miss: Language Spoken in Uganda: What Most People Get Wrong

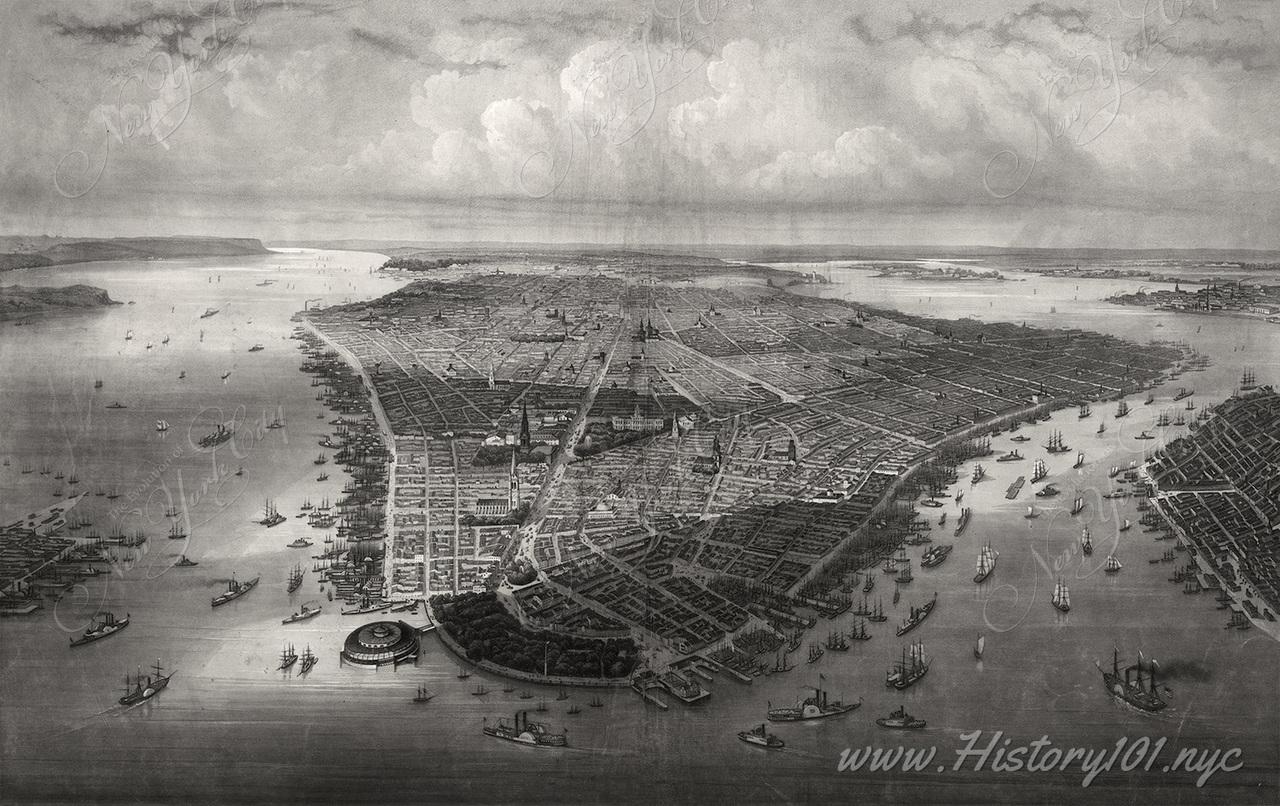

Chief Engineer Washington Roebling watched the construction through a telescope from his window because he was too sick to visit the site. The photos from the 1870s show the twin granite towers rising like ancient cathedrals over a harbor filled with sailing masts. It was the tallest thing in the Western Hemisphere for a while.

Then there was the "El."

Before the subway, we had elevated trains. They were steam-powered. Imagine walking down 6th Avenue and having hot cinders and grease rain down on your hat. That was life. Photos from the 1880s show these massive iron structures casting permanent shadows over the streets. It made the city feel industrial, loud, and dark.

Key archives for real research

If you're looking for the real deal and not just Pinterest reposts, you have to go to the source.

- The New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections: They have the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views. These were the 1800s version of VR—two photos side-by-side that looked 3D through a viewer.

- The Museum of the City of New York: Their online database is probably the most user-friendly for seeing how specific neighborhoods evolved.

- The Library of Congress: Essential for finding the high-resolution scans of early panoramic views.

The myth of the "clean" 19th century

We tend to romanticize the past because the photos are sepia-toned and look "classy."

The reality was filthy.

In 1880, there were about 150,000 horses in NYC. Each horse produced about 20 pounds of manure a day. Do the math. When it rained, the streets were a literal river of sludge. When it was dry, that stuff turned into dust that people breathed in.

When you look at New York City 1800s photos and see people holding their long skirts up while crossing the street? They weren't being dainty. They were trying to avoid a biohazard.

This is why the "White Wings"—the city's first real street cleaning force under George E. Waring Jr.—became such a big deal in the 1890s. Photos of these men in their bleached white uniforms sweeping the streets look like something out of a utopian movie because, compared to the filth of 1870, they basically were.

Seeing the vanished landmarks

Some of the coolest photos are of things that simply don't exist anymore.

The Crystal Palace was a massive iron and glass structure built for the 1853 World's Fair (The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations). It stood where Bryant Park is today. It was a masterpiece. Then it burned down in about 25 minutes in 1858. There are only a few rare daguerreotypes and prints that show it in its full glory.

🔗 Read more: Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser: Why Disney’s Most Ambitious Bet Actually Failed

Or the original Grand Central Depot.

Before the current Beaux-Arts masterpiece was built in 1913, there was a smaller, red-brick version with massive iron train sheds. Photos of 42nd Street in the 1870s show it looking almost rural compared to the neon chaos of today.

How to spot a fake or mislabeled photo

Social media is full of "history" accounts that get things wrong. Constantly.

You'll often see a photo labeled "New York in 1850" that features a building constructed in 1890. Here’s a quick tip: look at the streetlights. Gas lamps have a very specific, ornate look. If you see electric arc lamps, you're looking at at least the late 1870s or 1880s.

Check the hats. Men's fashion moved slow, but it did move. Wide-brimmed "wide-awakes" were huge in the 1860s. Derbies (bowlers) took over in the 80s and 90s. If everyone is wearing a fedora, you’ve slipped into the 1900s.

Also, look at the cobblestones. Early 1800s streets were often just dirt or rough "cobble" (natural round stones). Later in the century, they moved to "Belgian blocks"—those rectangular granite blocks you still see in parts of SoHo or DUMBO today.

Why we are still obsessed with these images

There’s something haunting about seeing a person from 1865 looking directly into the lens. They had no idea what the world would become. They were standing in the middle of a civil war, or a cholera outbreak, or the birth of the stock market, just trying to get home for dinner.

New York City 1800s photos remind us that the city is a living thing. It sheds its skin every few decades. The buildings in those photos are mostly gone, replaced by taller ones, which will eventually be replaced by something else.

But the energy? That's the same.

The guy selling oysters from a cart in 1845 has the same hustle as the guy selling halal chicken in 2026. The grit is the DNA of the city.

Actionable Steps for History Seekers

To see these photos in the highest possible quality and even find your own ancestors or neighborhood history, follow these steps:

- Use the NYPL "OldSF" style tools: While "OldSF" is for San Francisco, New York has "OldNY" (and similar map-based archives like Urban Archive) that pins historical photos to a modern map. Open a map-based photo app while walking through Lower Manhattan to see a "then and now" view in real-time.

- Search by "Sanborn Maps": If you find a photo of a building but aren't sure what it was, look up the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps from the late 1800s. They are incredibly detailed and show exactly what every building was made of and what business occupied it.

- Visit the Center for Brooklyn History: If your interest is the "Outer Boroughs," this archive holds the most comprehensive collection of 19th-century Brooklyn, which was actually a separate city until 1898.

- Check the "Library of Congress" Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC): Use specific search terms like "Stereograph New York" or "Manhattan 1870" to find TIF files that are massive in size—often 100MB or more. You can zoom in until you see the individual expressions on people's faces a block away.

The history is there. You just have to know where to dig.