You’re standing in the middle of a city you don’t know. Your phone is dead. You look at a physical map, or maybe just the sun, and suddenly that north west east south map layout in your head feels like a total mess. It happens to everyone. Honestly, most people think they understand the four cardinal directions, but the moment you take away the blue GPS dot, our internal compasses tend to crumble.

Orientation is a weirdly human struggle.

We’ve relied on these four points for thousands of years. From the early mariners using the Pole Star to the complex GIS systems running on your iPhone right now, the logic remains the same. But here’s the kicker: north isn't always north. If you’re looking at a standard map, you’re seeing a flat representation of a curved rock floating in space. That creates distortion. It makes things look closer or further than they really are, and it can totally screw up your sense of direction if you don't know what you're looking at.

The Problem With "Up" Being North

Most of us were taught that north is "up." That’s a total lie, or at least a very recent convention. Early Egyptian maps often put south at the top because the Nile flows north, so "up" was literally upstream. Medieval Christian maps (the Mappa Mundi) usually put east at the top because that’s where they believed the Garden of Eden was located. This is actually where we get the word "orientation"—it comes from oriens, the Latin word for east.

When you look at a north west east south map today, you’re looking at a product of 16th-century European navigation. Gerardus Mercator changed everything in 1569. He needed a map that helped sailors navigate with constant compass bearings. It worked for ships, but it made Greenland look as big as Africa. It’s not. Africa is actually fourteen times larger.

This matters because how we visualize the map changes how we move through the world. If you think of north as "up," you might subconsciously think of it as "higher" or "better." Research in behavioral psychology suggests people actually perceive traveling "up" a map as more difficult or time-consuming than traveling "down."

Understanding the Cardinal Points Without the Screen

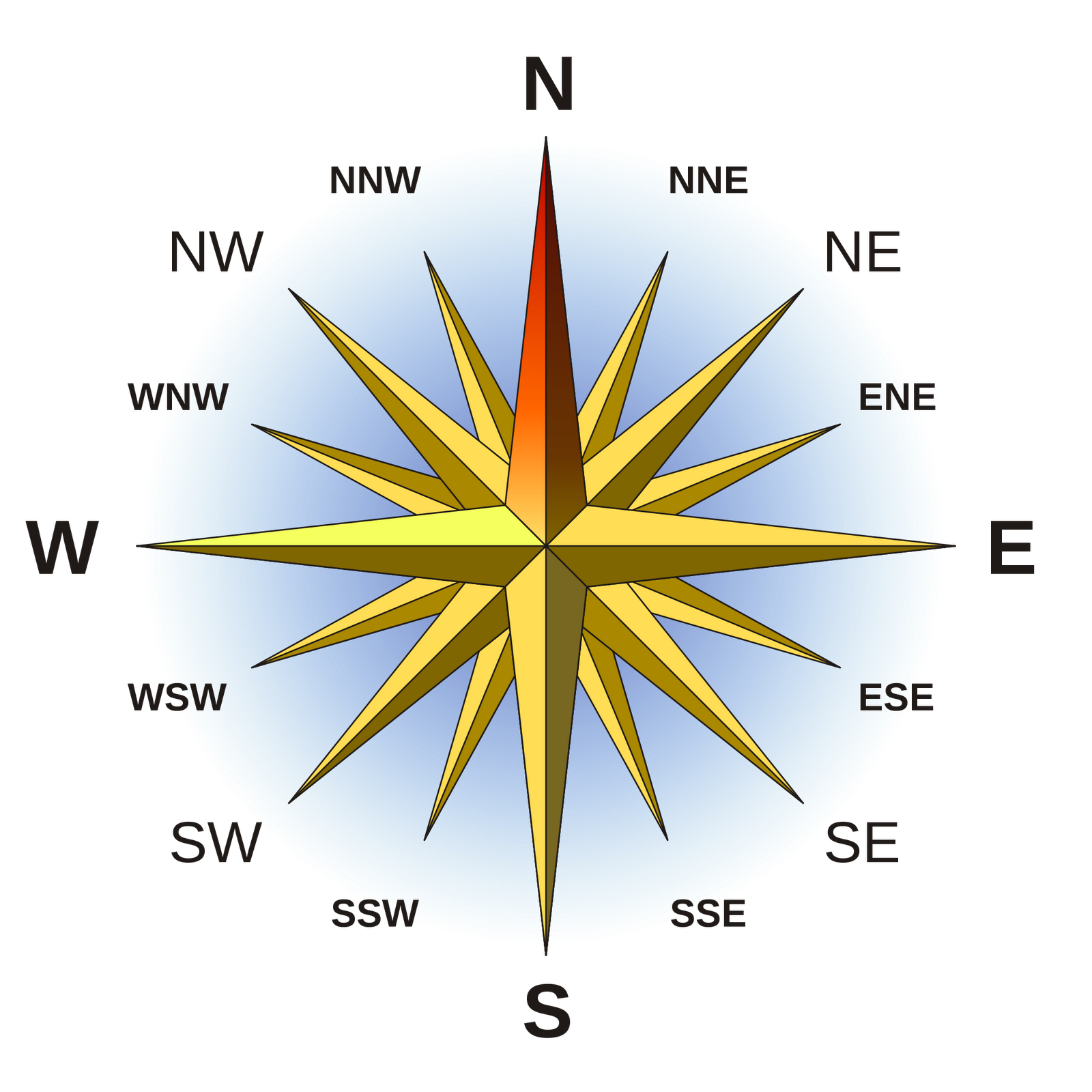

So, how do you actually find your way? You’ve got the four big ones:

North is the big boss. In the Northern Hemisphere, you find it via Polaris (the North Star). It’s the only star that doesn't seem to move because it’s aligned with the Earth's axis.

📖 Related: The New GMC Square Body Truck: Why Most People Get It Wrong

South is the opposite, obviously. If you’re in the Southern Hemisphere, you use the Southern Cross.

East and West are defined by the sun. But here’s a pro tip: the sun only rises exactly in the east and sets exactly in the west on two days of the year—the equinoxes. The rest of the year, it’s drifting. If you’re relying on a "close enough" sun-based north west east south map in the dead of winter, you might end up miles off course.

It's about the angles.

Think about the "Stick and Shadow" method. It’s ancient. You poke a stick in the ground, mark the tip of the shadow, wait twenty minutes, and mark it again. The line between those two marks is your east-west line. It’s crude, but it works when your tech fails.

Why Your Compass and Your Map Don't Agree

Ever heard of magnetic declination? It’s the annoying gap between "True North" (the North Pole) and "Magnetic North" (where your compass points). Magnetic north moves. It’s currently hauling tail from Canada toward Siberia at about 34 miles per year.

If you’re hiking in places like Washington state or Maine, the difference can be 15 degrees or more. If you follow your compass without adjusting your north west east south map for that offset, you’ll be hundreds of yards off your target within a single mile. Experienced hikers like those from the Appalachian Mountain Club drill this into people because "following the needle" blindly is a great way to get rescued by a helicopter.

The Psychology of Directional Bias

Some people are just "good with directions." But why? It's often because they maintain a "survey perspective" in their heads. Instead of thinking "turn left at the Starbucks," they are constantly updating a mental north west east south map.

🔗 Read more: Why the New Jersey University Crossword Clue Trips Everyone Up

There are cultures, like the Guugu Yimithirr people in Australia, who don’t even use words for "left" or "right." They use cardinal directions for everything. They’ll say, "Move your glass to the north-northwest." Because their language forces them to always know where they are, they have a "GPS" in their brains that never turns off. We’ve mostly lost that because we rely on turn-by-turn instructions that tell us what to do, rather than where we are.

How to Rebuild Your Mental Map

If you want to stop being the person who gets turned around in a parking garage, you have to practice. Start by identifying north every time you enter a new building. Look at the shadows. If it’s noon and you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, shadows point north. It’s a simple trick, but it keeps your brain tethered to the physical world.

Maps are just abstractions.

Whether it's a topographic map for a weekend trek or a digital map on your dashboard, it's just a tool. The real north west east south map is the relationship between your body and the planet.

- Check the legend: Always look for the "North Arrow." Don't assume the top of the page is north, especially on local park maps or mall directories.

- Observe the wind: In many regions, prevailing winds come from a consistent direction (like the "Westerlies"). If you know the wind usually hits your left cheek when you're walking north, you have a constant tactile cue.

- The Watch Method: If you have an analog watch, point the hour hand at the sun. The point halfway between the hour hand and the 12 o’clock mark is South (in the Northern Hemisphere). It’s surprisingly accurate.

Getting better at navigation isn't about memorizing every street name. It's about understanding the grid. Once you internalize the cardinal directions, the world stops being a series of confusing turns and starts being a coherent space you actually inhabit.

Actionable Steps for Better Navigation

- Download an offline map of your local area on Google Maps or Gaia GPS. This ensures you have the visual "north west east south" layout even without a cell signal.

- Learn your local declination. Go to a site like NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information and plug in your zip code to see how far off your compass is from True North.

- Ditch the GPS for one day. Try to navigate a familiar route using only cardinal directions. Force yourself to think, "I am heading East on 5th Street," instead of "I am turning right."

- Buy a baseplate compass. Practice "pointing" the map—physically rotating the paper map until the north on the paper aligns with the north in the real world. This is called orienting the map, and it is the single most important skill in land navigation.