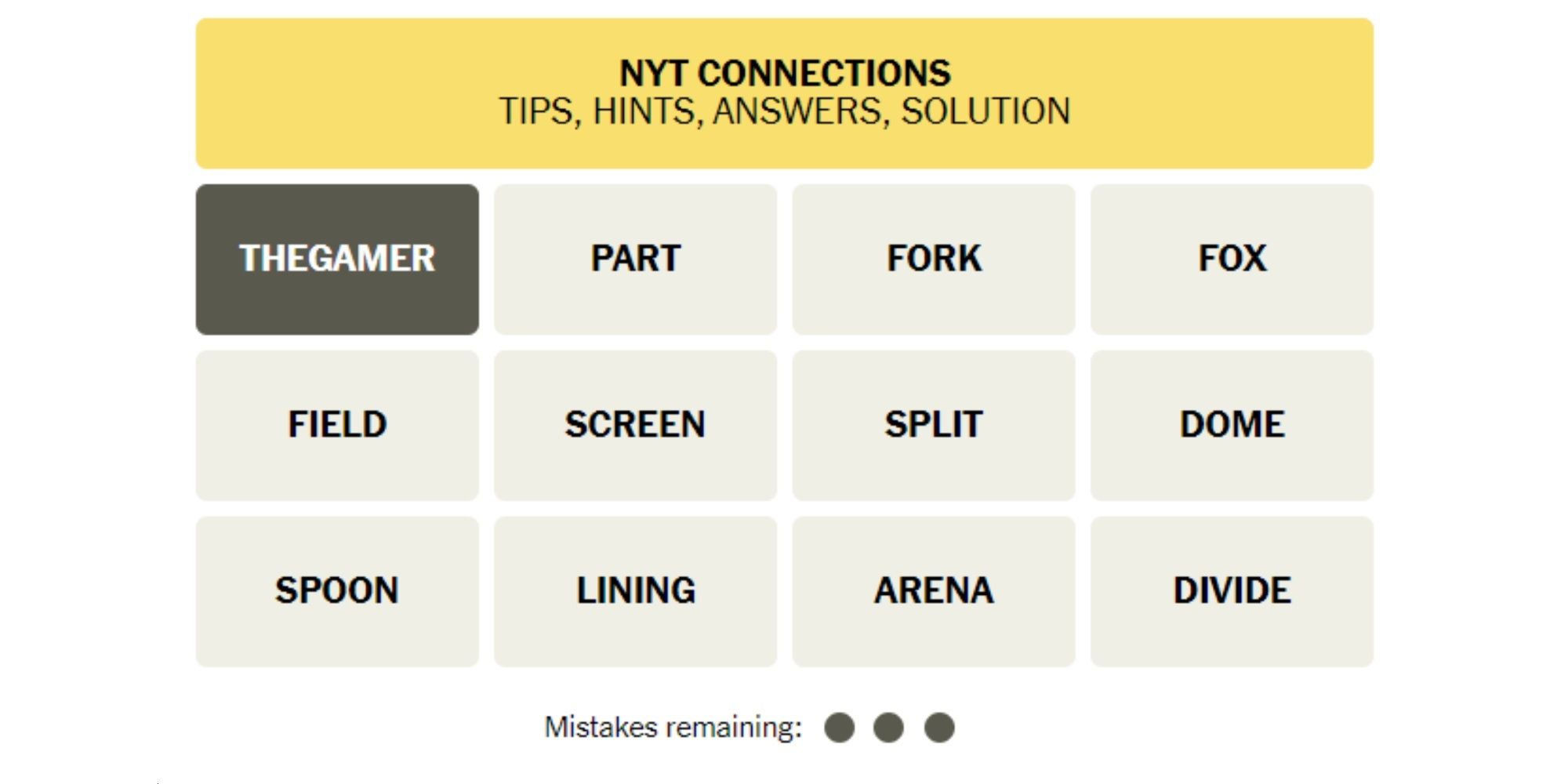

You’re staring at sixteen words. They seem random. "Bacon," "Cape," "Green," and "Ear." You think, "Okay, maybe these are just things that have... bits?" You select them. The grid shakes. One mistake down. You’ve got three lives left, and suddenly, the NY Times hints connections between these words feel more like a cruel joke than a morning hobby.

It’s frustrating.

Wyna Liu, the associate puzzle editor at The New York Times, isn't trying to ruin your morning, though it often feels that way. Since its beta launch in mid-2023, Connections has become a cultural staple, arguably rivaling Wordle for the most shared digital grid on social media. But while Wordle is a game of process and elimination, Connections is a game of psychological warfare. It relies on something linguists call "semantic priming." Your brain sees a word and immediately jumps to its most common definition. The game wins when you can't see past that first impression.

The NY Times Hints Connections Players Actually Need

Most people go into the grid looking for groups of four. That’s the first mistake. You shouldn’t be looking for groups; you should be looking for "spoilers." These are words that clearly belong in two different categories. If you see "Orange," you might think of fruit. But if you also see "Blue" and "Apple," you’re suddenly stuck between a color category and a tech giant category.

The game is designed with these overlaps. It’s intentional.

The real NY Times hints connections fans look for are the "purple" categories first. In the game’s internal logic, groups are color-coded by difficulty. Yellow is straightforward. Green is a bit more abstract. Blue usually involves specific knowledge or slightly more complex wordplay. Purple? Purple is the "blank" word category. It’s the "Words that start with a body part" or "Follows the word 'Sucker'." If you can spot the purple category early, the rest of the board collapses into place much more easily.

Honestly, the best way to play is to not press any buttons for at least a full minute. Just look. If you see "Bass," don't assume it's a fish. Is there an "Alto" or a "Tenor"? Is there a "Clef"? Or is it "Bass" like the beer? If you commit too early to the fish theory, you’ve already lost.

Why the "Red Herring" is the Game's Real Hero

The editors are masters of the red herring. They love using words that share a literal meaning but have no thematic link in that day's specific puzzle. For example, they might put in "Pound," "Ounce," and "Stone." You think: "Units of weight." Then you see "Kilogram." You click. Incorrect. It turns out "Stone" was meant for "Types of British Rock Bands" and "Pound" was for "Actions of a Gavel."

It’s brilliant and annoying.

📖 Related: The Untitled Goose Game Sun Hat: How to Pull Off the Ultimate Prank

A lot of the internal logic comes down to how we categorize information. According to cognitive science, our brains use "spreading activation." When you see the word "Doctor," your brain naturally "pre-heats" related concepts like "Nurse," "Hospital," or "Whom." The NY Times hints connections exploit this by giving you three words that fit a strong activation pattern and a fourth that is just slightly off, while the actual fourth word is hidden in plain sight under a different definition.

Breaking Down the Difficulty Curve

The game isn't just getting harder; it’s getting more referential. In the early days, categories were often "Kinds of Fruit" or "Parts of a Car." Now, we’re seeing categories like "Palindromes" or "Words that sound like letters."

- Yellow Categories: Usually synonyms. Think "Happy," "Cheerful," "Glad," "Joyful."

- Green Categories: Often nouns with a shared physical location. "Things in a gym" or "Items in a desk drawer."

- Blue Categories: Slightly more "knowledge-based." It might require knowing names of 1950s jazz musicians or specific legal terminology.

- Purple Categories: The "Meta" group. These are often linguistic tricks. "Words that can follow 'Sugar'" or "Homophones for numbers."

If you find yourself stuck on the NY Times hints connections for a specific day, try reading the words out loud. Sometimes the connection isn't semantic (meaning-based) but phonetic (sound-based). If you say "Eight," "Ate," and "Ait" (the island), you’ll hear the connection before you see it.

The Shuffle Button is Your Best Friend

Seriously. Use it.

Humans are visual creatures. We are prone to "functional fixedness," a cognitive bias that limits us to using an object only in the way it is traditionally used. In Connections, this translates to "spatial fixedness." If "Bat" is sitting next to "Ball," your brain will insist they are a pair. By hitting shuffle, you break those accidental visual associations. It forces your eyes to re-scan the grid and find links that were physically separated by the initial layout.

Some players even take it a step further. They write the words down on physical scraps of paper. It sounds like overkill, but moving the words around with your hands engages a different part of the brain than just tapping a screen. It helps you see the "NY Times hints connections" that are buried under layers of clever editing.

💡 You might also like: Baldur’s Gate 3 Adamantine Forge: Why Most People Craft the Wrong Items

Strategies for the Daily Grind

There’s a specific rhythm to a successful Connections session. Most "pro" players—if we can call people who play puzzles in their pajamas "pros"—follow a reverse-engineering path.

- Identify the overlap. Find the five or six words that could belong to the same category. Do not select them yet.

- Look for the odd man out. If you have five words for "Water," one of them must belong to a different, more specific group. Figure out which one.

- Find the Purple. Scan for wordplay. If you see "Knight," "Night," and "Nite," you’re looking at homophones.

- Process of elimination. Solve the Yellow and Green only when you’re 100% sure they aren't part of a tricky Blue or Purple.

The stakes feel high because the game is social. Sharing your grid on X (formerly Twitter) or in the family group chat is the modern version of the morning water cooler talk. No one wants to share a grid full of "X" marks. But remember, the game is designed to be a "five-minute break." If it’s taking you an hour, the editors have won.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

The most common mistake? Ignoring the "One Away" message. If the game tells you that you are "one away," it means three of your selected words are correct. Do not just swap one word and hope for the best. Stop. Look at the words you left out. Which one of those better fits the theme you’ve identified? Or, more importantly, is one of the three you did pick actually the red herring for a different category?

Another thing: watch out for the "Compound Word" trap. Sometimes "Fire" and "Work" are in the same puzzle, but they aren't meant to be "Firework." "Fire" might be in a "Things that can be 'Set'" category, while "Work" is in "Office Jargon." The editors love splitting compound words to bait you into a quick, incorrect guess.

The Evolution of the NY Times Games Suite

The success of Connections isn't an accident. It’s part of a broader strategy by the Times to turn their app into a destination for "habitual play." Since buying Wordle from Josh Wardle for a "low seven-figure" sum in 2022, they’ve learned that people crave short, punchy, intellectually stimulating games that offer a sense of completion. Connections fills the gap between the speed of Wordle and the commitment of the Crossword.

It’s a different kind of smart. You don't need a massive vocabulary to win at Connections. You need a flexible mind. You need to be able to see that "Sponge" isn't just something you clean with—it’s also a person who lives off others, a type of cake, and a verb meaning to soak up.

✨ Don't miss: Letter Scramble to Words: Why Your Brain Gets Stuck and How to Win

Actionable Steps for Tomorrow’s Grid

To stop losing your streaks and start seeing the NY Times hints connections like an editor, change your approach starting tomorrow.

- Don't click anything for the first 60 seconds. Force your brain to find at least three potential categories before you commit to one.

- Search for the "missing" word. If you see "Jacket," "Tie," and "Shirt," don't look for "Pants." Look for the word that isn't clothing but fits the group—maybe "Potato" (as in a potato jacket).

- Talk it out. Say the words. Use them in a sentence. Often, the context you use naturally will reveal the category the editor intended.

- Use the Shuffle tool. Use it often. Use it whenever you feel stuck. It’s the closest thing to a "hint" the game gives you without penalizing your score.

- Study the archives. If you missed a day, go back and look at the categories. You’ll start to see the "editor’s voice." You'll notice they have a penchant for 90s pop culture, basic kitchen items, and puns involving birds.

The game is a conversation between you and the puzzle creator. Once you start anticipating their tricks, the grid becomes less of a mystery and more of a predictable—though still challenging—dance. Check the grid, breathe, and remember: it’s just sixteen words. They can’t hurt you unless you let them.