You’ve heard it at hockey games. You’ve probably mumbled through it in a high school gymnasium while staring at a slightly dusty flag. But honestly, most people don’t realize that the national anthem of Canada O Canada has a history that is way more chaotic than the polite, melodic tune suggests. It wasn’t always the national anthem. In fact, for about a century, it was basically just a catchy local song from Quebec that English Canada eventually decided they liked enough to borrow—and then completely change.

The 100-Year Wait for Official Status

It’s wild to think about, but "O Canada" only became the official national anthem on July 1, 1980. Before that, Canada was in a bit of a weird spot. We used "God Save the Queen" (or King, depending on the decade) because of our British roots. There was also "The Maple Leaf Forever," which was super popular in English-speaking provinces but... let’s just say it wasn’t a hit in Quebec.

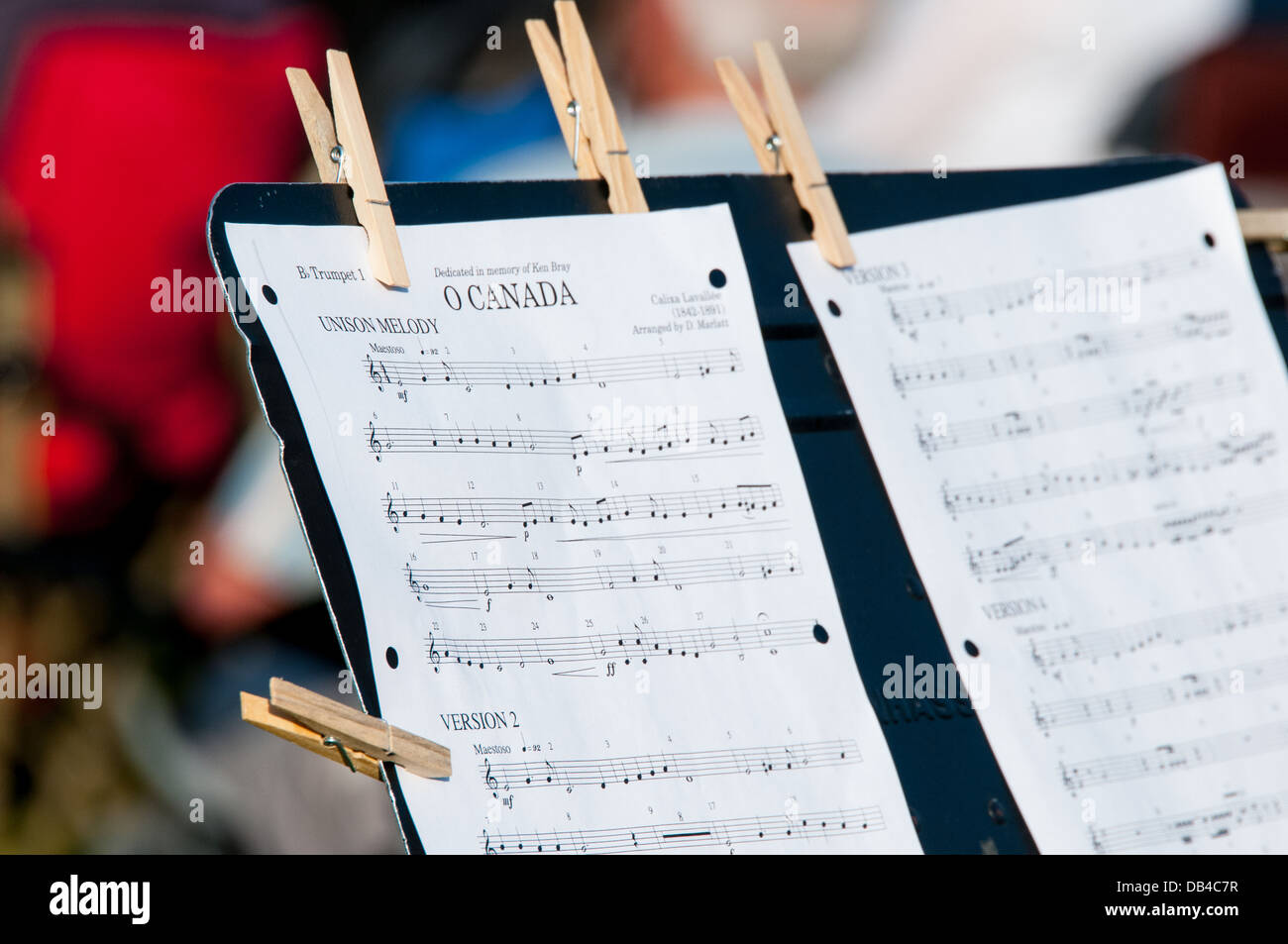

The music itself was composed by Calixa Lavallée in 1880. That’s a full hundred years before it got the "official" stamp from Parliament. Lavallée was a fascinating guy—a veteran of the American Civil War (he played the fife for the Union) who wanted to create something majestic for a Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day banquet in Quebec City. He succeeded. The music is technically a march in 4/4 time, though we usually sing it like a slow, swelling hymn today.

The original French lyrics were written by Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier. If you speak French, you know those lyrics are intense. While the English version talks about "glowing hearts" and "standing on guard," the French version is full of imagery about carrying swords and crosses. It’s a very different vibe.

The Lyric Wars: Why We Changed "Sons"

One of the biggest controversies in recent memory happened in 2018. You might remember the headlines. The line "True patriot love in all thy sons command" was officially changed to "True patriot love in all of us command."

Some people were furious. They felt like history was being erased. But here’s the kicker: the original 1908 English version by Robert Stanley Weir didn’t even have the word "sons" in it.

- 1908 Original: "Thou dost in us command."

- 1913 Revision: "In all thy sons command."

- 2018 Official: "In all of us command."

Weir changed it to "sons" right before World War I, likely as a nod to the men headed off to the front. So, the 2018 change wasn't actually some brand-new "woke" invention; it was more of a return to what the song originally intended before the wartime edits took over. It took 12 different bills introduced in Parliament over several decades to finally get that change passed.

A Tale of Two Different Songs

If you actually look at a side-by-side translation of the French and English versions, they aren’t even the same song. Like, at all.

✨ Don't miss: 10 day la weather forecast: Why the January Heat Wave is Tricking Everyone

In English, we sing about the "True North strong and free." That specific phrase actually comes from a poem by Lord Tennyson. It’s all about the landscape and the general idea of protection.

The French lyrics, "Ô Canada! Terre de nos aïeux," focus on "land of our ancestors" and "flowery brows." It talks about "carrying the sword" and "carrying the cross." It’s much more rooted in the specific religious and military history of New France. When you hear a singer do the bilingual version at a Blue Jays game, they are jumping between two completely different philosophies of what Canada actually is. One is about the land; the other is about the lineage.

The Forgotten Verses

Hardly anyone knows there are actually four verses to the English version. We only ever sing the first one. The other verses are... a lot. They include lines like "Where pines and maples grow" and "Ruler supreme, who hearest humble prayer."

The fourth verse is almost entirely a prayer. This is part of why the anthem remains a point of debate for secularism advocates. While the English version is somewhat vague with "God keep our land," the French version is deeply Catholic in its origins.

👉 See also: Rousseau on Social Contract: Why Most People Totally Misunderstand Him

Why It Still Matters

National anthems are weird. They are these frozen-in-time artifacts that we try to force into the modern world. For Canada, "O Canada" represents the constant tug-of-war between our French and English identities. It’s a song written by a French-Canadian, popularized by a Royal Tour in 1901, and finally legalized by a government trying to figure out what it meant to be a sovereign nation in the 80s.

If you’re ever at a ceremony and want to show off your knowledge, remember that you don't need permission to perform it. Since 1970, the government has owned the copyright (they bought it for $1), but it's effectively in the public domain for all Canadians to use.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Event:

- Check your lyrics: If you have old sheet music or programs, ensure they reflect the 2018 change ("in all of us command") to avoid an awkward social faux pas.

- Bilingual is better: If you're organizing a national event, the "official" bilingual version is the gold standard. It toggles between the two languages to respect both founding cultures.

- Tempo check: If you’re playing a recording, look for a "Maestoso" (majestic) tempo. If it’s too fast, it sounds like a circus march; too slow, and everyone loses their breath by the final "stand on guard."

- Protocol: You don't actually have to take your hat off by law (it’s a custom, not a legal requirement), but standing is the universal sign of respect across all provinces.

The song is essentially a living document. It has changed before, and given how much Canadians love to debate their own identity, it wouldn't be surprising if it changes again in another fifty years. For now, it remains the primary soundtrack to our national pride—swords, crosses, maples, and all.