You’ve been there. You sit down to draw a simple hallway or a street scene, and halfway through, everything looks... off. The buildings seem to be leaning away from you. The floor feels like it’s sliding off the page. It’s frustrating because you can see the 3D world clearly in your head, but the paper refuses to cooperate. This is usually where people give up on one perspective point drawing and just label themselves "not an artist."

But honestly? It’s just math disguised as art.

Linear perspective was the massive "cheat code" of the Renaissance. Before Filippo Brunelleschi started poking holes in painted canvases to prove his geometric theories in the early 1400s, art was basically flat. People were sized by their importance—kings were huge, peasants were tiny—not by how far away they stood. One perspective point drawing changed all of that by introducing a single, logical anchor: the vanishing point.

The Vanishing Point Isn't Just a Dot

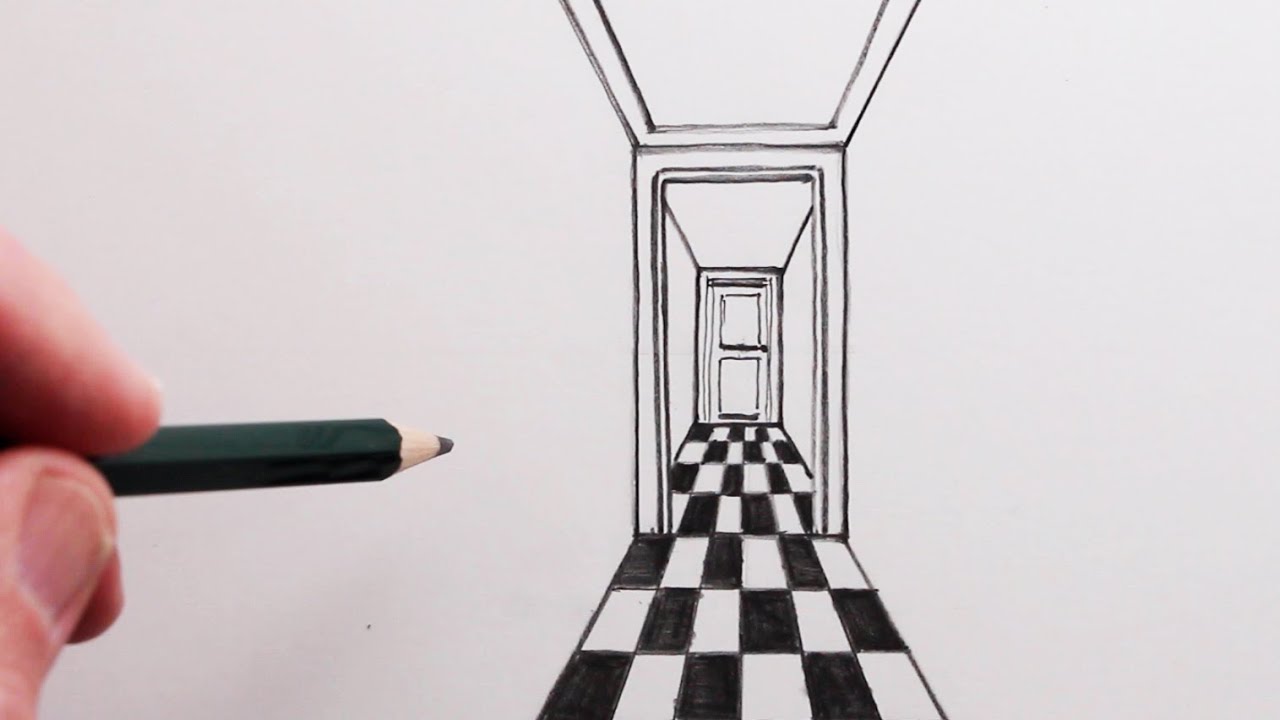

Most beginners treat the vanishing point like a chore. They plot a dot in the middle of the horizon line and then forget about it. That’s a mistake. In a one perspective point drawing, that single dot is the sun around which your entire universe orbits. Every single depth line—what pros call "orthogonals"—must return to that point.

Think about standing on train tracks. You know the rails are parallel. They never touch. If they did, the train would derail. But your eyes are lying to you. Because of how light hits your retina, those rails appear to merge at a single spot on the horizon. That’s the core of the whole system.

If you are drawing a room, and the top of the door frame doesn't point directly to your vanishing point, the door will look like it's swinging into a different dimension. It’s binary. It’s either right, or it's wrong. There’s very little "vibes-based" sketching when you're working with formal perspective.

Getting the Horizon Line Right

Your horizon line is literally your eye level. If you sit on the floor, the horizon line drops. If you climb a ladder, it rises. A common trap in one perspective point drawing is placing the horizon line way too high, which makes the viewer feel like they’re hovering over the scene like a drone.

👉 See also: Fordham Rd Grand Concourse: Why This Bronx Intersection is the Real Heart of New York

Keep it natural.

If you want a grounded, human feel, put that line right across the middle or slightly below. This creates a sense of scale. When you place objects above the horizon line, we see their bottoms. Below it? We see their tops. It sounds simple, but you’d be surprised how many people draw a table below the horizon line and then forget to draw the tabletop.

Why Your "3D" Boxes Still Look Fake

Even when people get the lines pointing to the right spot, their drawings often feel "stiff." This usually happens because they ignore the scale of recession.

Basically, things don't just get smaller as they go back; they get thinner.

If you’re drawing a fence, the distance between the first and second post is wide. The distance between the tenth and eleventh post should be a tiny sliver. If you keep the spacing equal, the fence will look miles long but also weirdly flattened. This is a quirk of human perception that artists like Leonardo da Vinci obsessed over. He realized that to make a one perspective point drawing feel real, you have to account for "atmospheric perspective" too—the way things get lighter and blurrier as they hit the vanishing point.

The Power of the "True Shape"

One of the coolest things about this specific technique is that the "front" of every object remains undistorted. If you’re drawing a cube in one-point perspective, the face looking at you is a perfect square. No weird angles. No slanted lines. Just a square.

- Draw the front face (a square or rectangle).

- Connect the four corners to the vanishing point.

- Draw the "back" of the box by mimicking the front shape between those connecting lines.

That’s it. That’s the whole secret. If the front of the object is parallel to your face, you use one-point perspective. If the object is turned at an angle where you see a corner first, you’ve drifted into two-point territory, which is a whole different headache involving two vanishing points.

Common Blunders Even Pros Make

Don't get cocky. Even people who have been sketching for years mess up the "transversals." Those are the horizontal and vertical lines that define the width and height of objects.

In a standard one perspective point drawing, your vertical lines must be perfectly vertical. 90 degrees. Straight up and down. If you tilt them even slightly, you’re accidentally introducing three-point perspective, which makes buildings look like they are looming over the viewer or falling backward.

Another big one? Putting the vanishing point off-center.

Actually, wait. That’s not a blunder; it’s a choice. While putting the point dead center creates a "Wes Anderson" symmetrical look, moving it to the left or right makes the scene feel more dynamic. It forces the viewer’s eye to travel across the page. Just make sure your lines actually go there. If you have two different objects in the same room and they aren't parallel to each other, you can't use the same vanishing point. That’s a advanced trap. For a basic room, though, one point is your best friend.

Real World Evidence: The Last Supper

If you want to see the pinnacle of this, look at da Vinci’s The Last Supper. He didn't just use perspective for depth; he used it for narrative. The vanishing point is literally Christ’s right temple. Every architectural line in the room—the tops of the tapestries, the ceiling coffering—leads the viewer’s eye directly to the main subject.

It’s a psychological trick.

By using one perspective point drawing, Leonardo ensured that no matter where you look in the painting, your eyes are eventually funneled back to the center of the story. You can use this in your own work. Want someone to look at a specific door in your drawing? Position your vanishing point near it. The lines of the floor and walls will act like arrows pointing the way.

Actionable Steps to Master the Depth

Stop reading and actually grab a pencil. Theory is boring; doing it is where the "click" happens.

- Tape your paper down. Use masking tape. If the paper shifts while you’re using a ruler, your vanishing point is toast.

- The String Trick. Instead of constantly drawing and erasing lines, pin a piece of string to your vanishing point. Pull it tight to any corner of your drawing to instantly see where your line should go. It saves a mountain of eraser shavings.

- Start with a "Viewfinder." Take a piece of cardboard, cut a rectangular hole in it, and look at a hallway in your house. Identify the one spot where all the lines seem to meet. That’s your vanishing point in the wild.

- Practice "The Grid." Draw a floor grid first. It’s the easiest way to understand how squares turn into trapezoids as they move toward the horizon. Once you can draw a tiled floor, you can draw anything.

Don't worry about being "artistic" yet. Treat the first ten sketches like a blueprint. Use a ruler. Be precise. Once the geometry is in your muscle memory, you can start to loosen up and sketch those perspective lines by hand. The most "lifelike" drawings are usually the ones where the underlying grid is perfect, but the final lines are a little shaky and human.

Mastering one perspective point drawing is about learning to see the world as it actually hits your eye, rather than how your brain thinks it should look. It’s the difference between a drawing that stays on the paper and one that looks like you could walk right into it.