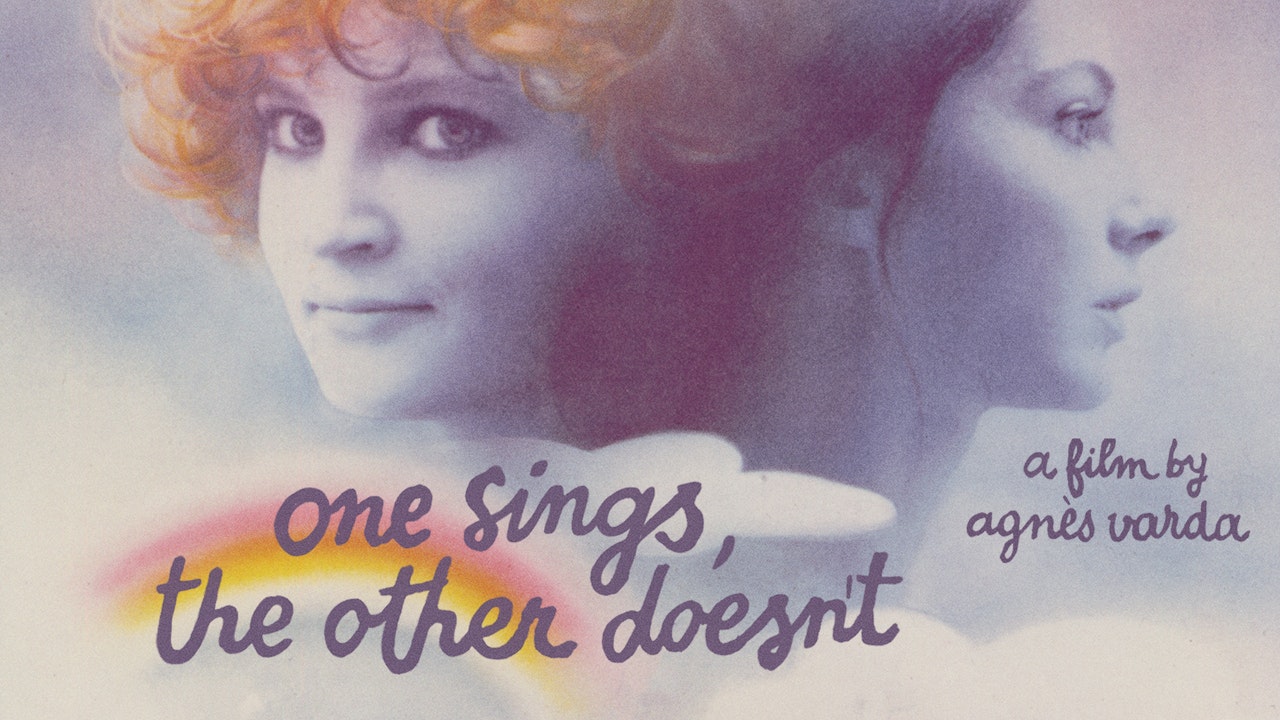

Agnes Varda was never one for the "rules" of cinema. When people talk about the French New Wave, they usually bring up Godard’s jump cuts or Truffaut’s moody kids. But Varda? She was interested in how life actually feels when you're stuck in the middle of it. One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (original title L’une chante, l’autre pas) is basically the ultimate proof of that. Released in 1977, it’s a movie that feels startlingly modern because it handles things like reproductive rights and female friendship without the usual heavy-handed melodrama you’d expect from a "political" film.

It’s a story about Pomme and Suzanne. They are different. One sings, the other doesn't. Simple, right? Not really.

The Raw Reality of Pomme and Suzanne

The movie kicks off in 1962 Paris. We meet Suzanne, a young mother struggling with two kids and a third on the way, living in a cramped photography studio with a partner who is basically drowning in his own depression. Then there's Pauline (who later becomes Pomme), a middle-class schoolgirl with a rebel streak and a voice that wants to be heard.

What’s wild is how Varda uses a real-life tragedy—a suicide—to link these two women. It’s not "fun" cinema, but it’s honest. After Suzanne’s partner takes his own life, the two women drift apart, only to reunite ten years later at a protest for abortion rights. This isn't just a plot point; it's a reflection of the actual Manifesto of the 343, a famous 1971 petition signed by French women who admitted to having illegal abortions. Varda herself was a signer. She wasn't just making a movie; she was filming the movement she lived in.

Why One Sings the Other Doesn't Hits Different Today

You’ve probably seen movies about "girl power." They usually involve a makeover montage or a shared boyfriend. Varda skips that. Instead, she focuses on the logistical nightmare of being a woman in the 70s.

Suzanne moves back to the countryside, eventually running a family planning clinic. Pomme joins a radical feminist folk-pop group. This is where the title comes alive. Pomme’s singing isn't just a hobby. It’s her way of processing the world. The lyrics are blunt—sometimes almost awkwardly so—talking about pregnancy, bodies, and freedom. While she’s out on the road being a bohemian artist, Suzanne is doing the slow, grinding work of social change in a small town.

One sings. The other doesn't. Both are essential.

The film manages to be a musical without being a "Musical." It doesn't have the polished glitz of Hollywood. It has the vibe of a home movie that happens to be a masterpiece. The colors are saturated, the pacing is a bit loose, and honestly, that’s why it works. It feels like a long letter from a friend.

The Politics of the Body

Let's get into the heavy stuff. Varda was obsessed with "cine-writing." To her, the camera was a pen. In One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, she uses that pen to describe the Bobigny trial of 1972, a landmark legal case in France where a minor was tried for having an abortion after a rape.

✨ Don't miss: Where Can You Watch Straw and Why This Short Film Is Still Making Waves

The movie doesn't shy away from the messy parts of the pro-choice movement. It shows the tension between wanting a family and wanting a life. Pomme eventually moves to Iran with a man she loves, becomes pregnant, and realizes that even "progressive" men can be incredibly restrictive. She chooses to return to France to have her second child on her own terms. It’s a radical choice even by 2026 standards. She likes being a mother, but she refuses to be just a mother.

Suzanne, meanwhile, finds a different kind of liberation. Her path is quieter. It involves education, community, and eventually a stable, healthy relationship. Varda is telling us there isn't one "correct" way to be a feminist. You can be the woman on stage with the guitar, or you can be the woman behind the desk making sure people get the healthcare they need.

The Aesthetic of "The Other"

Visually, the film is a feast. Varda worked with cinematographer Charlie Van Damme to create a look that felt "feminine" in its softness but "masculine" in its directness. There’s a lot of natural light. There are lots of flowers.

But look closer.

The "other" in the title isn't just Suzanne. It’s the version of ourselves we leave behind. Throughout the film, we see the characters through their correspondence—postcards, letters, photos. This was the social media of the 70s. It’s how they stayed connected across distances. It highlights a specific kind of female intimacy that is built on shared secrets and long-distance support.

🔗 Read more: Why the circus comes to town is still a billion-dollar cultural phenomenon

A Legacy of Joy (Yes, Really)

A lot of people hear "1970s feminist film" and think it’s going to be a miserable slog. It’s not. One Sings, the Other Doesn’t is surprisingly joyful. It’s full of "happiness as a subversive act."

Varda believed that women being happy on their own terms was a form of revolution. When Pomme sings about her "mimi" (her vagina) or the joy of birth, it’s not meant to be provocative for the sake of it. It’s meant to reclaim the narrative.

Critics at the time were sometimes baffled. Some thought it was too "sweet" or "utopian." But looking back, that optimism is its greatest strength. It envisions a world where women aren't competitors, but collaborators. Even when they don't see each other for years, the bond remains.

How to Watch and What to Look For

If you’re going to sit down and watch this, don't expect a fast-paced thriller. It meanders. It breathes.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Favorite Teams on The Amazing Race Usually Lose (and Who Actually Wins)

- Pay attention to the lyrics. They were written by Varda herself. They are essentially the film’s manifesto.

- Watch the background. Varda often used non-professional actors and filmed in real locations. The people in the protest scenes? A lot of them were actual activists.

- The Iranian sequence. It provides a sharp contrast to the European setting and adds a layer of global perspective that was rare for French cinema at the time.

- The ending. It jumps forward in time to show the next generation. It’s a reminder that the struggle for rights is a relay race, not a sprint.

Making the Connection to Now

It’s easy to think we’ve moved past the issues in One Sings, the Other Doesn’t. But with the shifting landscape of reproductive rights globally, the movie feels more like a documentary than a period piece.

The film teaches us that the personal is always political. Your choice of partner, your career, how you raise your kids—it’s all part of the larger song. Whether you’re the one singing at the top of your lungs or the one doing the quiet work in the background, your presence matters.

Varda’s masterpiece reminds us that friendship is a political structure. It’s a safety net. It’s a way to survive a world that wasn't necessarily built for you.

Actionable Steps for Film Lovers

If this movie resonated with you, there are a few ways to dive deeper into this specific era of filmmaking and thought.

- Explore the "Left Bank" Cinema: Varda was part of the Left Bank group, which was more interested in literature and social issues than the mainstream New Wave. Check out Chris Marker or Alain Resnais to see the stylistic cousins of this film.

- Read the Manifesto of the 343: It provides the essential historical context for the abortion rights scenes in the movie. Understanding the risk those women took makes the protest scenes hit much harder.

- Watch 'Varda by Agnès': This was her final film, a documentary where she explains her own process. It’s the perfect companion piece to understand why she chose to tell Pomme and Suzanne’s story the way she did.

- Host a "Double Feature" Night: Pair One Sings, the Other Doesn’t with a modern film like Never Rarely Sometimes Always. Comparing the 1970s French experience with the modern American one is an eye-opening exercise in how much has changed—and how much hasn't.