Ever tried sketching a character laughing or shouting, only to end up with something that looks like a Muppet or a dark, bottomless void? It’s frustrating. You’ve got the eyes perfect, the hair is flowing, but that gaping hole in the middle of the face ruins the whole vibe. Honestly, making an open mouth drawing easy isn't about being a master of anatomy; it’s about understanding that the mouth isn't just a line that opens up. It’s a 3D structure that changes the entire shape of the jaw.

Most beginners make the mistake of drawing a circle on top of a static face. That’s why it looks "pasted on." If you want to get this right without spending four years in art school, you have to look at the mechanics of the mandible. When we talk, our chin doesn't just drop straight down like a garage door. It swings on a hinge.

📖 Related: How to Say Dick in Spanish: The Messy Truth About Slang Across Borders

The "Banana" Method for Simple Mouth Shapes

Forget those complex anatomy books for a second. Think about a banana. Seriously. When you're aiming for an open mouth drawing easy enough for a quick sketchbook entry, use the curve of a banana as your base for the lower lip.

The upper lip is basically a flattened "M." The lower lip is a soft "U." When the mouth opens, that "U" moves further away from the "M," but it also stretches. The corners of the mouth (the cheilion) are the anchors. They don't move nearly as much as the center of the chin does. If you draw a wide-open mouth and keep the corners in the same spot they were when the mouth was closed, your character will look like they’re screaming in a very unnatural, stiff way.

Why the Teeth Are Your Enemy

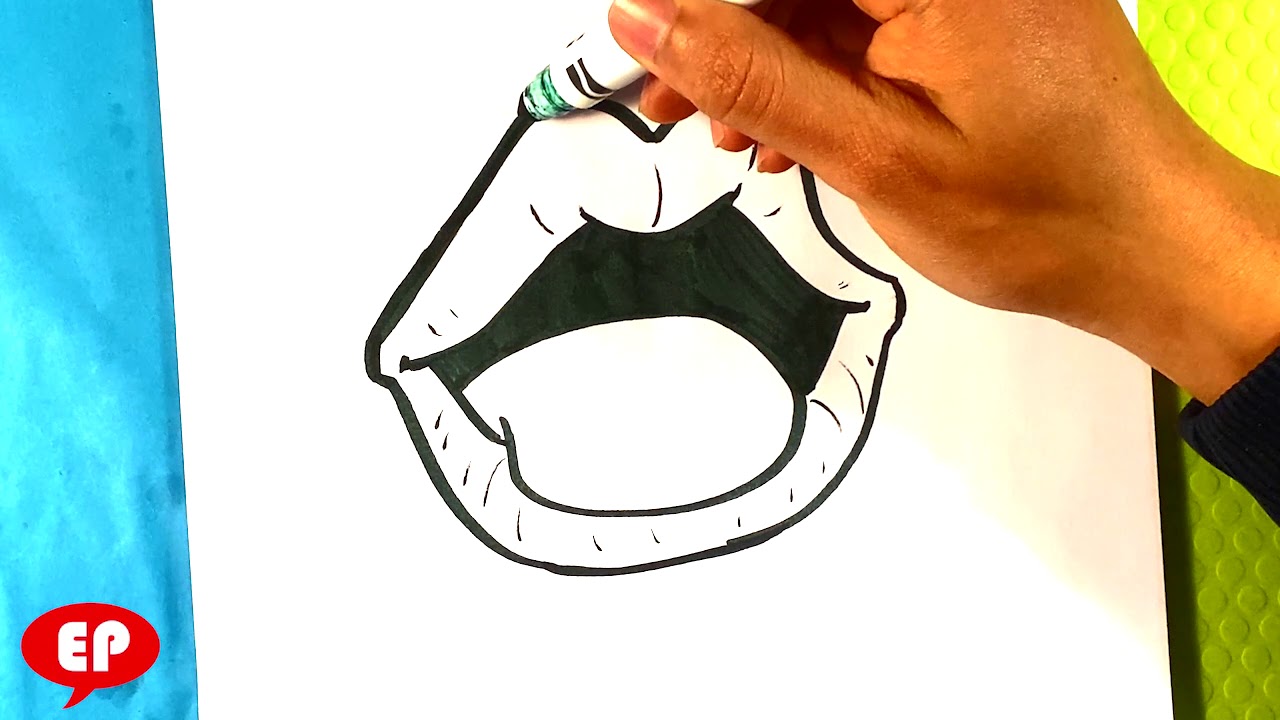

Here is a hot take: stop drawing every single tooth. Just stop. When people search for a way to make an open mouth drawing easy, they often get bogged down in the dental details. Unless you’re doing a hyper-realistic medical illustration or a portrait of a dental patient, drawing individual lines for every tooth makes the character look like they have "chiclet" teeth or, worse, a mouthful of piano keys.

Instead, think of teeth as a single white shape. A "block" of light.

- Draw the dark void of the throat first.

- Layer a soft white or off-white shape for the upper teeth.

- Keep the bottom teeth hidden or barely visible unless the mouth is opened incredibly wide.

In most natural expressions, the upper teeth are much more prominent. The lower teeth usually stay tucked behind the lower lip. Look at any photo of a person laughing. You’ll see the top row clearly, but the bottom row is often obscured by shadow or the lip itself.

The Jaw Hinge: The Secret to Depth

If you want your open mouth drawing easy to actually look three-dimensional, you have to realize the jaw is a hinge. Grab your own chin. Open your mouth. Feel how your jaw moves down and slightly back toward your neck?

If you just extend the chin straight down on your paper, the face looks like it's being stretched like taffy. To fix this, you need to tilt the chin slightly. This creates a more realistic silhouette. It’s the difference between a flat cartoon and a character that feels like they have bones and muscle.

The tongue also matters more than you think. It's not just a flat red rug sitting at the bottom of the mouth. It’s a thick muscle. When the mouth is open, the tongue might be pressed against the bottom teeth, or it might be arched if the person is making a "La" or "Th" sound. For a basic "easy" drawing, just a slight hump at the bottom of the oral cavity is enough to give it a sense of "realness."

Common Mistakes That Ruin the Look

- The Black Hole Effect: Filling the inside of the mouth with pure, solid black. Real mouths have shadows, yes, but they also have a tongue, a uvula (sometimes), and a back of the throat that catches a little light. Use a dark burgundy or a deep brown instead of flat black.

- Ignoring the Cheeks: When the mouth opens wide, the cheeks stretch thin. The "smile lines" (nasolabial folds) become more pronounced. If the mouth is huge but the cheeks are still plump and round, it looks like a filter, not a face.

- The Floating Lip: The bottom lip is attached to the chin. If the chin moves, the lip must move.

Perspective Changes Everything

Drawing a mouth from the front is one thing. Doing it from a three-quarter view is where most people quit. In a three-quarter view, the "center" of the mouth shifts. The side of the mouth further away from the viewer will look shorter and more compressed.

Think of the mouth as being wrapped around a cylinder—because the teeth and jaw are curved. It’s not a flat sticker on a flat board. You’ve got to wrap those lips around the curve of the face.

Lighting the Interior

Since we're keeping this open mouth drawing easy, let's talk about the simplest lighting trick. Imagine a flashlight shining into the mouth. The top teeth will cast a shadow on the tongue. The upper lip will cast a shadow on the top teeth.

By adding just one small shadow under the upper lip and one small shadow where the tongue meets the floor of the mouth, you've suddenly created depth. You don't need fancy blending stumps. A simple pencil or a slightly darker marker will do the job.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

Start by drawing a simple oval for the head. Mark the eyeline. Now, instead of drawing a line for the mouth, draw a "dropped" jaw shape. Basically, extend the chin lower than you think you should.

Once you have that elongated face shape, place the upper lip. It stays relatively close to the nose. Then, place the lower lip near the bottom of your new, extended chin. Connect them at the corners with slightly curved lines.

Fill the space between them with a dark color, but leave a white "strip" at the top for the teeth. Don't draw vertical lines for the teeth! Just leave it as a solid white bar. Then, add a small, pale pink "mound" at the bottom for the tongue.

This simplified approach works for comics, anime, and even basic realism. It strips away the overwhelming anatomical data and focuses on what the eye actually sees: a dark space, a flash of white teeth, and a change in the jawline.

To take this further, spend five minutes in front of a mirror making the most ridiculous faces you can. Watch how your cheeks pull and how your chin moves. Real-world observation is the only way to move past the "symbol drawing" phase where you're drawing what you think a mouth looks like instead of what it actually is. Focus on the corners of the mouth—they are the most expressive part of the entire lower face. If you get the corners right, the rest usually falls into place.

Once you master the basic "hinge" movement of the jaw, you can start experimenting with more complex angles, like looking up into the mouth or drawing a "sneer" where one side of the mouth is higher than the other. The foundation remains the same: the jaw moves, the lips stretch, and the teeth stay as a block. Keep the lines soft, avoid the "black hole" trap, and remember that the chin is part of the equation. Drawing a mouth isn't just about the lips; it's about the entire lower half of the head working in unison.