You probably think you know how Monopoly started. An unemployed salesman named Charles Darrow, desperate during the Great Depression, has a "eureka" moment in his basement, sketches out a board on a circular piece of oilcloth, and sells it to Parker Brothers to become a millionaire. It’s a classic American Dream story. It's also mostly a lie. The original monopoly game 1935 wasn't a sudden invention; it was a corporate acquisition of a folk game that had been played for decades by Quakers and left-wing intellectuals.

The 1935 version we recognize today—the one with the red hotels and the silver thimble—actually represents the moment a political protest tool was polished into a commercial juggernaut.

Honestly, the real story is way more interesting than the corporate myth. It involves a feminist inventor named Lizzie Magie who created The Landlord’s Game in 1903 to teach people about the dangers of monopolies. She wanted to show how rent-seeking enriches landlords and impoverishes tenants. Fast forward thirty years, and Charles Darrow is playing a modified version of Magie's game with friends in Atlantic City. He writes down the rules, gives it the iconic visual flair we love, and the rest is history. But if you look at a 1935 set today, you’re looking at the exact point where "teaching a lesson" turned into "winning it all."

Why the 1935 Black Box Sets are the Holy Grail

If you’re a collector, you know the "Black Box." 1935 was a chaotic year for the game’s production. Parker Brothers wasn't even sure it would be a hit. Initially, they rejected Darrow's pitch, claiming it had "52 fundamental errors," including the fact that it took too long to play and the rules were too complicated. They only changed their minds after seeing the massive sales Darrow was generating on his own through Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia.

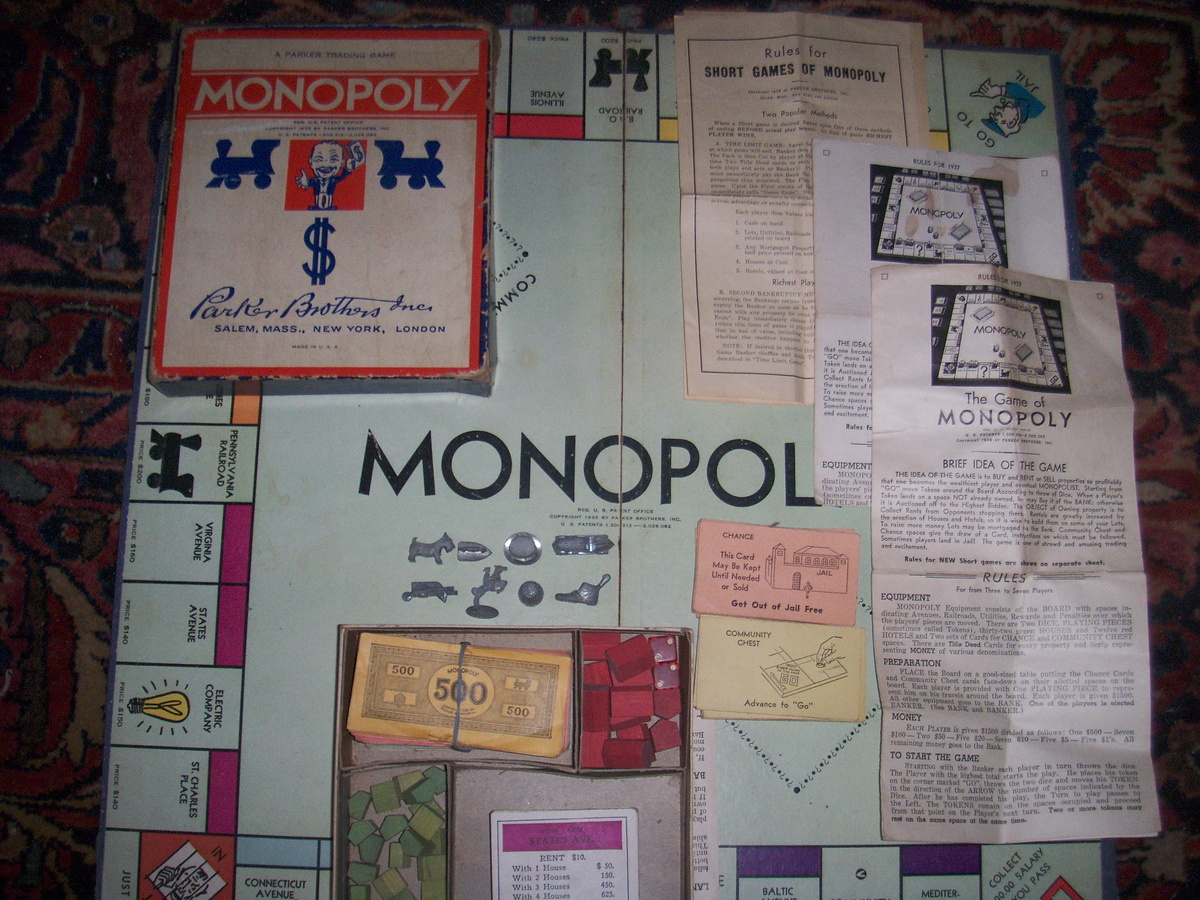

When Parker Brothers finally took over in 1935, they released several versions. The most famous is the #7 Black Box. It’s minimalist. It’s heavy. It feels like a relic from a different era. The board wasn't actually inside the box; it was sold as a separate piece.

Early 1935 sets are weirdly inconsistent. Some have "Patent Pending" stamped on them because the legal rights were still a mess. Parker Brothers was frantically buying up patents from Lizzie Magie and other "Monopoly" variant creators to ensure they had a total... well, monopoly on the game. They paid Magie a mere $500 for her patent. No royalties. No fame. Just five hundred bucks for the foundation of a billion-dollar franchise.

The Design Quirk of the Original Monopoly Game 1935

Have you ever noticed that the Monopoly man (Rich Uncle Pennybags) isn't on the 1935 box? He didn't even exist yet. The 1935 aesthetic was purely about the typography and the street names.

Darrow’s genius—or the genius of the people he "borrowed" the game from—was the use of Atlantic City locations. Marven Gardens? That’s a misspelling of "Marvin Gardens" that persisted for decades because Darrow made a typo on his original oilcloth board. The 1935 edition solidified these mistakes into legend.

The tokens were also different. In the very first sets produced by Darrow, he suggested players just use charms from their wives' charm bracelets. When Parker Brothers took over, they introduced the metal tokens we know, but the lineup was fluid. You might find a cannon, a thimble, a shoe, or a ship. These weren't just toys; they were symbols of the era's industry and domestic life.

The Two-Game Problem

There’s a nuance here that most casual players miss. The original concept by Lizzie Magie had two sets of rules: "Anti-Monopolist" and "Monopolist." In the anti-monopolist version, everyone was rewarded when wealth was created. In the monopolist version, you won by crushing everyone else. Guess which one Parker Brothers chose to market in 1935?

They knew that people struggling through the Depression didn't want a lesson in social justice. They wanted the fantasy of being the one who owned the whole town. They wanted to be the person collecting $200 for passing GO, not the person stuck in Reading Railroad's debt.

📖 Related: South Park: The Stick of Truth Still Feels Like a Long Lost Season of the Show

Identifying a True 1935 First Edition

If you find a set in your grandma's attic, don't get excited just because it says "1935." That date refers to the copyright, and Parker Brothers printed that date on boxes for years. To know if you have a true original monopoly game 1935 masterpiece, you have to look at the fine print.

- The "Darrow" Logo: Real early sets often have "C.B. Darrow" or "Parker Brothers" written in a very specific, understated font.

- The Board Color: The 1935 boards had a distinct blue-green hue that aged into a sort of muddy olive.

- The Houses: Early 1935 sets used wooden houses and hotels. Plastic didn't become the standard until much later, around the time of World War II when metal and wood were needed for the war effort.

- The Patent Number: If the box says "Patent 2,026,082," it was produced after December 31, 1935. If it says "Patent Pending," you’ve likely found a much more valuable early-run set.

The sheer variety of 1935 editions is staggering. There was the #6 Blue Box, the #7 Black Box, and the #9 "Gold Edition." Each had slightly different component qualities. The #7 is the one most people associate with the "original" look, featuring the game name in a bold, black serif font across a white label.

The Cultural Impact: Why it Exploded in 1935

Why then? Why, in the middle of the worst economic collapse in history, did people flock to a game about real estate speculation?

Psychologists have argued about this for years. Basically, Monopoly offered a sense of control. You could lose your real house to the bank on Monday, but on Tuesday night, you could own Boardwalk and Park Place. It was a safe space to be greedy. It was a "lifestyle" game before that was even a term.

📖 Related: Why Spider Man the Game PS2 is Still the Best Movie Tie-In Ever Made

Edward P. Parker, who was the president of the company at the time, once admitted he didn't even like the game at first. He thought it was too long. But the public's obsession was undeniable. By the end of 1935, Parker Brothers was churning out over 20,000 sets a week. They couldn't keep up. The game literally saved the company from bankruptcy.

The Atlantic City Connection

The choice of Atlantic City wasn't random. In the 1930s, Atlantic City was the "World's Playground." It was the premier vacation spot for the East Coast elite. By using these names, Darrow gave the game an aspirational quality.

Interestingly, some of the street names have changed or disappeared in real life since 1935. Illinois Avenue was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd in the 1980s. But in the world of the 1935 original, these places are frozen in time. St. Charles Place doesn't exist anymore—it was wiped out by the construction of the Showboat Atlantic City casino.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Rules

Most people play "House Rules" without realizing they are ruining the game's balance. The 1935 rulebook is very clear about things like:

- No Free Parking Money: There is no "pot" of money in the middle. Putting money on Free Parking just makes the game last three hours longer than it should and causes everyone to hate each other.

- Auctions: If you land on a property and don't buy it, that property must go to auction immediately. This is the most ignored rule in Monopoly history.

- Housing Shortages: In 1935, if the bank ran out of wooden houses, you couldn't just use pennies or buttons. You had to wait until someone sold theirs or upgraded to a hotel. This was a strategic move to "lock" other players out of developing their properties.

If you play by the strict 1935 rules, the game is actually a fast-paced, cutthroat experience that usually ends in about 45 to 60 minutes. It was meant to be a brutal simulation of capitalism, not a four-hour marathon of boredom.

📖 Related: Zombie War Tycoon Codes: How to Get Cash Without the Grind

The Legacy of the 1935 Edition

Today, the original monopoly game 1935 is a piece of Americana. It represents a shift in how we spend our leisure time. Before Monopoly, most games were "race games" like Parcheesi, where you just tried to get from point A to point B. Monopoly introduced the idea of engine building and player-driven economies.

It’s also a reminder of the "Great Theft" of Lizzie Magie's idea. While Darrow is the name on the box, the spirit of the game belongs to the various groups—Quakers, socialists, and college students—who played it and refined it for thirty years before it ever saw a printing press.

If you’re lucky enough to own a 1935 set, you don't just own a game. You own a snapshot of a country trying to reinvent itself through play.

Actionable Insights for Collectors and Enthusiasts

- Check the Patent: If you are buying an "original" set, look for the "Patent Pending" or "Patent 2,026,082" marks. This is the quickest way to date the set.

- Verify Components: Ensure the houses and hotels are wood. Metal tokens should be heavy, and the "Money" should feel thinner and more like tissue paper than modern Monopoly bills.

- Preservation: If you have an original board, store it flat. The 1935 boards were notorious for warping because of the glue used to bind the paper to the cardboard.

- Play the Original Way: Try a game using the "Auction" rule and no "Free Parking" money. It completely changes the dynamic and makes you appreciate the 1935 design's actual intent.

- Research the History: Read The Monopolists by Mary Pilon. It’s the definitive book on the legal battles and the true origins of the game, debunking the Darrow myth in incredible detail.