You’re standing on the South Rim. The wind is whipping, the air is thin, and for a second, you feel that weird, magnetic pull of the abyss. Most people step back, take a selfie, and walk to the gift shop. But then there are the ones who don't. Since it first hit the shelves in 2001, Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon has become the unofficial bible for anyone obsessed with the darker side of the National Park Service. Written by Thomas M. Myers and Michael P. Ghiglieri, this isn't some sensationalist tabloid rag. It’s a massive, meticulously researched clinical history of how people lose their lives in one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

It’s a thick book. Heavy. It’s the kind of thing you see people reading in the lodge at El Tovar while they wait for their dinner reservation, probably feeling a mix of morbid curiosity and a sudden urge to double-check their water bottle.

🔗 Read more: Athens Weather: What Most People Get Wrong

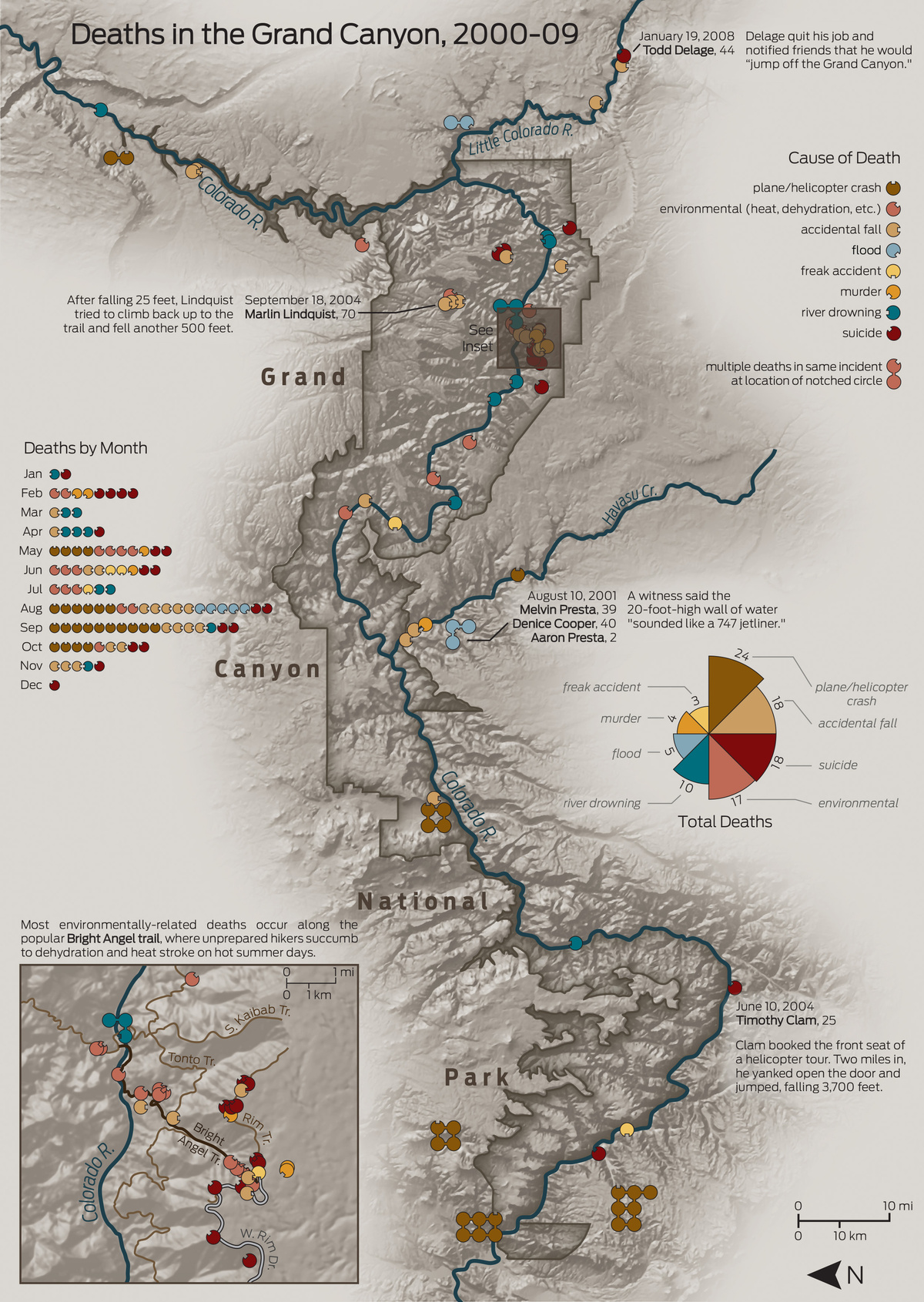

Why do we read this stuff? Honestly, it’s because the Grand Canyon is a place of extremes that humans aren't really built for. Myers and Ghiglieri don't just list names; they dissect the psychology of the "fatal error." They look at the 1956 mid-air collision over the canyon that basically birthed the FAA. They talk about the "suicide by canyon" phenomenon. They go into the gritty, heat-exhaustion-induced delirium that kills experienced hikers. If you’ve ever wondered about the deaths in Grand Canyon book and why it stays on the bestseller list at the park's visitor centers, it’s because it serves as a brutal, necessary reality check for a landscape that looks like a painting but acts like a predator.

The 1956 Disaster That Changed Aviation Forever

People think most deaths in the canyon are people falling off the edge. Not true. Some of the most significant chapters in the deaths in Grand Canyon book deal with the sky, not the dirt. On June 30, 1956, two commercial flights—United Airlines Flight 718 and TWA Flight 2—collided directly over the canyon. 128 people died.

At the time, there was no real air traffic control in that space. Pilots just... looked out the window.

The wreckage was scattered across the Chuar and Temple Buttes. Recovery was a nightmare. This single event is why we have the Federal Aviation Administration today. Myers and Ghiglieri lay this out with a level of detail that makes your skin crawl, describing how the search parties had to navigate the vertical terrain just to reach the debris. It’s a reminder that the canyon’s danger extends thousands of feet into the air.

Falling: The Psychology of the One Last Step

Falling is the big one. It’s what everyone fears. But the "how" is usually weirder than you’d think. There’s a specific section in the deaths in Grand Canyon book that deals with "The Fall."

It’s rarely a slip on a wet rock.

Sometimes it’s a joke gone wrong. There’s the famous (and horrific) account of a young man who pretended to fall to scare his friends, only to actually lose his footing and plummet hundreds of feet. Then there are the people who hop over the railings to get a better photo. They think they’re agile. They aren't. The rock at the rim is Coconino Sandstone and Kaibab Limestone—it’s crumbly. It’s deceptive.

You’ve got to realize that the canyon creates a weird optical illusion. Because everything is so massive, your brain loses its sense of scale. You think that ledge is three feet away; it’s actually ten. You think you’re balanced, but the wind at the rim can gust at 50 miles per hour without warning. Myers, a physician at the canyon, has seen the aftermath. He writes about it with a clinical detachment that somehow makes the tragedies feel more personal.

Flash Floods and the Hidden Danger of Side Canyons

If you're down at the bottom, the rim doesn't matter. The water does.

Flash floods in the Grand Canyon are terrifying. You can be standing under a clear blue sky in a slot canyon while a thunderstorm forty miles away sends a wall of chocolate-colored water, logs, and boulders screaming toward you. The book recounts the 1997 Antelope Canyon tragedy (technically outside the park but relevant to the region's geography) and similar events within the park boundaries. When that water comes, there is nowhere to go. You can’t climb fast enough. The mud makes the walls slick.

The Heat is a Quiet Killer

Most hikers who die in the Grand Canyon don't fall. They just stop moving.

The "Internal Heat" section of the deaths in Grand Canyon book is probably the most important for any tourist to read. The temperature difference between the South Rim and Phantom Ranch can be 30 degrees or more. You start your hike in 70-degree weather and descend into a 110-degree oven.

Hyponatremia is a word you’ll learn from Myers. It’s when you drink so much water that you flush the salt out of your system, your brain swells, and you die. It’s the "marathoner's death." People think they’re doing the right thing by chugging gallons of water, but without electrolytes, they’re basically drowning their cells. The authors highlight the case of Margaret Bradley, a 24-year-old marathon runner who died of dehydration in 2004. If a fit, young athlete can't survive a wrong turn in the heat, what chance does a tourist with a single 16-ounce Dasani have?

Honestly, the book is a masterclass in "what not to do." It’s a series of "if onlys."

- If only they had stayed with the group.

- If only they hadn't hiked at noon in July.

- If only they hadn't tried to jump that gap for a photo.

Why We Can't Put the Book Down

There is a certain type of person who visits the Grand Canyon and immediately buys the "Death" book. It’s not just about gore. It’s about respect. The Grand Canyon is one of the few places left where the "safety bumpers" of modern life don't really exist. If you walk off a cliff, there is no "undo" button.

The deaths in Grand Canyon book—which has been updated multiple times to include new incidents—acts as a totem. By reading about the mistakes of others, we feel like we’re buying a little bit of protection. We’re acknowledging that the wilderness is indifferent to our existence.

Ghiglieri and Myers also cover the river. The Colorado River is a freezing, churning beast. People flip rafts in Crystal Rapid or Lava Falls and vanish. The river doesn't care if you’re a pro or a novice. The book details the harrowing stories of "The Lost" — the people whose bodies were never found, swallowed by the silt and the deep holes of the canyon floor.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

If you’ve spent any time with this book, you realize the Park Rangers aren't joking when they put up those "Heat Kills" signs with the picture of the vomiting hiker. Here is how you actually survive the scenarios described in the text:

- The 10:00 AM Rule: If you are hiking into the canyon in the summer, you should be off the trail or in the shade by 10:00 AM. Period. Do not hike between 10 and 4.

- Eat Salt: Water isn't enough. You need pretzels, electrolytes, or salt tablets.

- Stay Away from the Edge: Seriously. Wind gusts and crumbly rock are a lethal combo.

- Don't Hike Alone: Many of the "missing person" cases in the book involve solo hikers who took a "shortcut" that wasn't a shortcut.

- Listen to the Rangers: If they say a trail is closed or a storm is coming, believe them.

The deaths in Grand Canyon book isn't meant to scare you away from the park. It's meant to keep you alive so you can see it again. The canyon is a masterpiece of geology, but it’s also a graveyard for the overconfident. Respect the scale, respect the heat, and keep your feet on the path.

✨ Don't miss: Barley Creek Brewing Company: Why This Pocono Landmark Still Matters After 30 Years

To get the most out of your visit, pick up a copy of the latest edition of Over the Edge at the Grand Canyon Conservancy stores. Read it at night by your campfire or in your hotel room. It’ll change the way you look at the view the next morning. You’ll see the beauty, but you’ll also see the power.

Check the National Park Service's official "Hike Smart" guide before you even pack your bags. Compare the weather at the rim versus the bottom using the NOAA forecast specifically for Phantom Ranch. Pack a signaling mirror and a whistle—items that could have saved dozens of the people mentioned in Myers' research. Make sure someone at home knows your exact itinerary and your "overdue" time. Preparedness is the only real antidote to becoming a footnote in the next edition.