You’ve probably seen the photos. Or at least, you think you have. Usually, it’s a shot of a kayaker struggling through a thick, neon-colored soup of plastic bottles and detergent jugs. Or maybe it’s a massive, solid island of trash where people are actually standing. Here’s the weird thing: those famous pacific garbage patch images are almost never actually from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

It’s a bit of a letdown, honestly.

The reality is way more subtle and, frankly, much scarier. If you sailed right through the middle of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre today, you might not even notice you were in a "patch" at all. You wouldn’t see a floating island. You’d see blue water. But if you dipped a fine-mesh net into that water and pulled it up, you’d find a plastic confetti soup that shouldn't be there.

The big lie in your image search

Most of the viral photos labeled as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) are actually taken in harbors in Manila, or after a tsunami in Japan, or near river mouths in Central America. Why? Because a photo of "clear" water with microscopic specks doesn't get clicks. We want the drama. We want the "Trash Island."

But there is no island.

Captain Charles Moore, who famously "discovered" the patch in 1997 while racing his yacht Alguita from Hawaii to California, didn't describe a landfill. He described a "plastic soup." Think of it less like a rug on the floor and more like a handful of glitter tossed into a swimming pool. The glitter is everywhere, but you can still see the water.

💡 You might also like: Trump and Iran Unconditional Surrender: What Most People Get Wrong

This creates a massive problem for scientists and activists. How do you convince the world to care about a disaster they can't see from a satellite?

What the Pacific garbage patch images actually show

If you look at verified photos from The Ocean Cleanup—the Dutch non-profit founded by Boyan Slat—the imagery changes. You see massive floating barriers catching "ghost nets" (discarded fishing gear). These nets make up about 46% of the mass in the GPGP. They aren't colorful soda bottles; they are tangled, barnacle-encrusted nightmares that drown sea turtles and crush coral reefs.

Then there are the microplastics.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) emphasizes that most of the plastic here has been hammered by UV rays and salt water until it’s smaller than a pencil eraser. In a lot of legitimate pacific garbage patch images, you’ll see researchers holding up a glass jar. Inside, the water looks cloudy. Those aren't air bubbles. Those are fragments of polyethylene and polypropylene.

Why the "Island" myth persists

It’s easier for our brains to process a solid object. If it’s an island, we can imagine sending a bulldozer to scoop it up. Since it’s actually a trillion-piece puzzle spread over 1.6 million square kilometers—an area twice the size of Texas—the solution is much harder.

🔗 Read more: Motorcycle Accident Riverside CA: What Local Riders Actually Need to Know About the Inland Empire Roads

The role of the "Gyre"

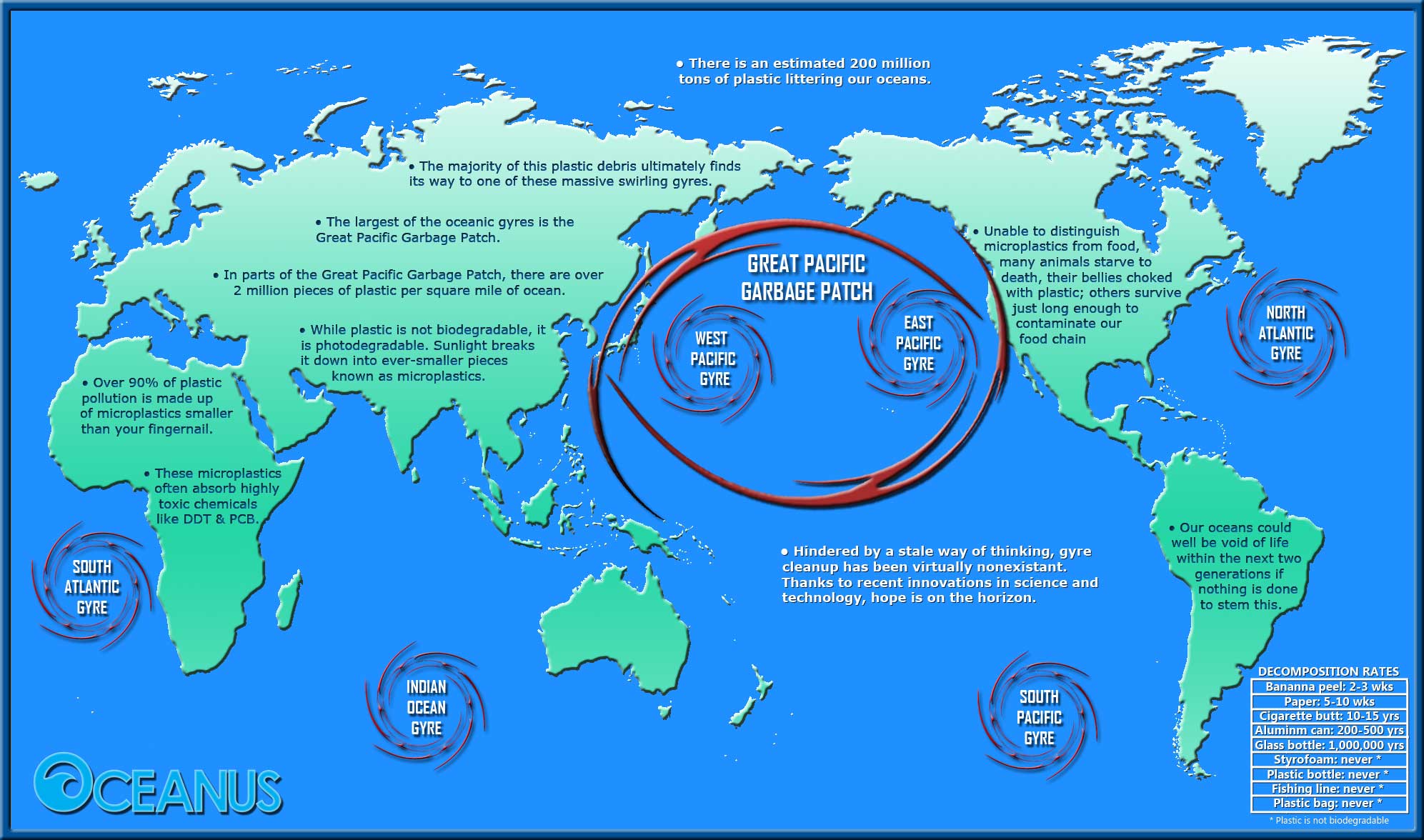

The GPGP isn't sitting still. It’s held together by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a system of four circulating currents:

- The California current

- The North Equatorial current

- The Kuroshio current

- The North Pacific current

These currents act like a slow-motion whirlpool. Trash gets sucked in and stays there. Some of it eventually sinks. In fact, a lot of what we see in pacific garbage patch images is just the tip of the iceberg. Oceanographers like Laurent Lebreton have published studies showing that while the surface gets the attention, the seabed underneath might be the final resting place for the heaviest plastics.

Microplastics and the food chain

This isn't just about ugly photos.

The plastic fragments look like food. To a sea turtle, a floating plastic bag looks like a jellyfish. To a surface-feeding fish, a white bead of plastic looks like a fish egg. A study from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography found plastic in the stomachs of 9% of the fish they sampled in the patch. That plastic contains toxins like PCBs and DDTs, which don't just stay in the fish. They move up. They end up on dinner plates.

Is it getting worse?

Yes. Despite the massive cleanup efforts, we are putting plastic into the ocean faster than we can take it out. Every time you see a "satisfying" video of a cleanup boom pulling in a haul of trash, remember that it's a drop in the bucket. We produce over 400 million tons of plastic globally every year.

The photography of a "Ghost"

If you want to see what the patch really looks like, look for the work of photographers who specialize in macro-photography. They aren't shooting the horizon. They are shooting the "neuston"—the layer of life at the very surface of the water.

In these images, you'll see "Blue Buttons" (Porpita porpita) and violet sea snails tangled up with blue plastic pellets. It’s a strange, haunting mimicry. The plastic has become part of the ecosystem. It’s a habitat now. Small crabs and bryozoans actually live on the floating debris, traveling thousands of miles away from their natural coastal homes. Scientists call these "neopelagic" communities.

✨ Don't miss: Bedford Weather Radar: What Most People Get Wrong About Tracking Storms in the Blue Ridge

How to spot a fake image

Next time you see a photo claiming to be the GPGP, check for these red flags:

- Too much wood: The GPGP is mostly plastic and gear. If you see a ton of logs and branches, it’s likely storm runoff near a coast.

- Dense enough to walk on: If it looks like a solid landmass, it’s almost certainly a harbor or a river mouth.

- Skyline in the background: The GPGP is in the "horse latitudes." It’s incredibly remote. If you see land in the distance, it’s not the patch.

Taking real action beyond the screen

Looking at pacific garbage patch images usually leaves people feeling helpless. It’s a big ocean. But the experts—the people out there actually pulling the nets—say the same thing: the cleanup starts at the source.

- Audit your own synthetic shed: Most microplastics in the ocean actually come from synthetic clothing (polyester/nylon) shedding fibers in the wash. Using a laundry filter can stop thousands of fibers from reaching the ocean.

- Support the "Interceptors": Organizations like The Ocean Cleanup are now placing "Interceptors" in the world's most polluting rivers. Stopping the plastic before it hits the gyre is infinitely more effective than chasing it across the Pacific.

- Avoid "Degradable" traps: Many plastics labeled "biodegradable" only break down in industrial composters, not in the cold, salt water of the North Pacific. They just turn into microplastics faster.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch isn't a place you can visit and stand on. It's a chemical change in our ocean's composition. It's a shift in the biology of the sea. Seeing it for what it actually is—a massive, invisible, plastic smog—is the first step toward actually fixing it.

Actionable Next Steps

To actually make a dent in the reality behind these images, start by installing a microfleece laundry bag or a permanent washing machine filter to catch synthetic fibers. Then, shift your support toward "upstream" solutions; donating to or advocating for river-based plastic interception prevents the trash from ever reaching the North Pacific Gyre. Finally, use tools like the NOAA Marine Debris Program's website to verify the source of environmental imagery before sharing it, ensuring the public conversation stays grounded in scientific reality rather than viral myths.