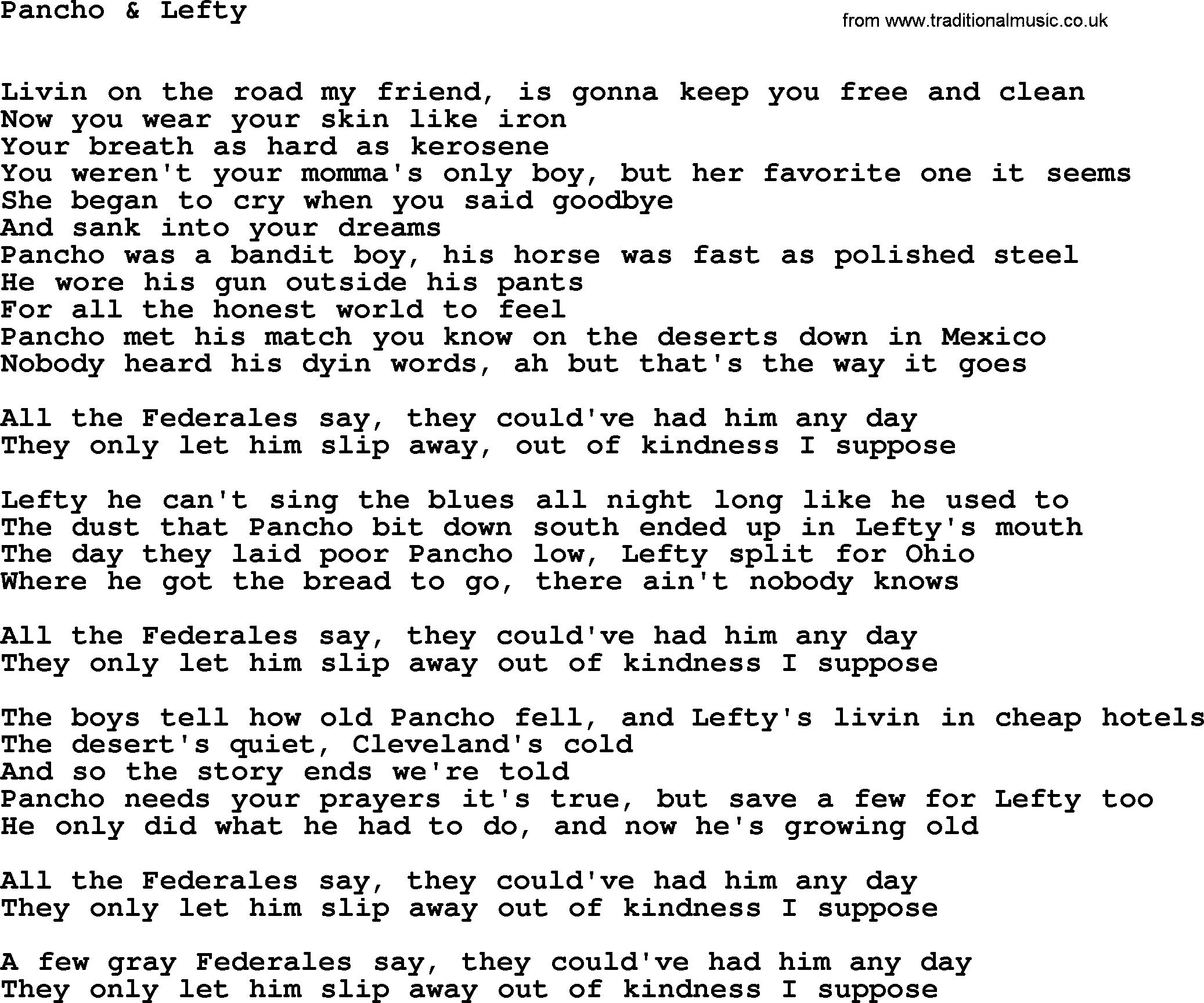

Townes Van Zandt was broke. He was stuck in a windowless hotel room in Denton, Texas, watching the news because there wasn't much else to do. On the screen, the police were apprehending two guys. They called them Pancho and Lefty. Townes sat down, and the song just sort of drifted through the window. That’s how he told it, anyway. He claimed he didn't even write it—he just "recorded" it from the air.

Most people hear Pancho and Lefty lyrics and immediately think of the Mexican Revolution. They think of Pancho Villa. They think of dusty federales and the desert heat of Chihuahua. But if you look closer, the song isn't a history lesson. It’s a ghost story. It’s a song about the crushing weight of survival and the price you pay for not dying young.

The Myth of the Mexican Robin Hood

Let’s get the historical stuff out of the way first. Pancho Villa was a real guy. He was a general in the Mexican Revolution, a folk hero to some, and a bandit to others. He was assassinated in 1923 in Parral, Mexico. But in Townes’ song, Pancho dies alone in the desert while his "horse is fast as polished steel."

Wait. Polished steel?

That's a weird way to describe a horse. Unless, of course, the horse isn't a horse at all. Some fans argue the horse is a car, or even a metaphor for the fast life that eventually catches up to you. Honestly, Townes was always vague about this. He once told an interviewer that he didn't know why he wrote it that way. He just liked the sound of the words.

The lyrics tell us that Pancho met his end because "the cold wind finally got him." It wasn't a bullet from a rival general. It was exhaustion. It was the world finally being done with him. This is where the song shifts from a ballad about an outlaw into something much more depressing. It’s about the myth vs. the reality.

Who the Hell is Lefty?

If Pancho is the fallen hero, Lefty is the guy who stayed behind. He’s the one who "split for Ohio." Why Ohio? Because it’s the most un-outlaw place Townes could think of. It’s gray. It’s industrial. It’s safe.

There is a long-standing theory that Lefty is the one who betrayed Pancho. The lyrics say, "The dust that Pancho bit down south / ended up in Lefty’s mouth." Then, suddenly, Lefty has enough money to get out. He’s "living in a cheap hotel." He’s got "the blues."

💡 You might also like: Julie Andrews: The Story of Who Played the Original Mary Poppins

You don't get the blues because you’re a successful businessman. You get the blues because you sold out your best friend for a bus ticket to Cleveland and a life of anonymity.

Why the Willie and Merle Version Changed Everything

In 1983, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard covered the song. It went to number one. It became a massive hit, and suddenly, everyone knew the Pancho and Lefty lyrics. But here’s the thing: they sang it like a straight-up cowboy song.

Willie has that sweet, nasal vibrato. Merle has that rugged, baritone authority. Together, they made the song sound legendary. But Townes’ original version? It’s haunting. It’s sparse. When Townes sings it, he sounds like he’s mourning his own life. He sounds like Lefty.

Interestingly, Willie Nelson reportedly didn't even know what the song was about when they recorded it. He just liked the melody. It wasn't until later, after he’d performed it hundreds of times, that the weight of the betrayal in the lyrics really started to sink in.

Decoding the Poetry of the Road

The song starts with a warning to a mother. "Living on the road, my friend / was gonna keep you free and clean."

It’s a lie.

Everyone who has ever spent time touring or traveling knows the road doesn't keep you clean. It makes you dirty. It wears you down. Townes knew this better than anyone. He spent most of his life living out of suitcases, struggling with addiction, and playing for crowds that didn't always listen.

When he writes about Pancho’s mother "clasping her hands to her heart," he isn't just writing a character. He’s writing about the families left behind by every drifter, musician, and outlaw who ever thought they could outrun their own shadow.

📖 Related: The Harry Potter Wand Quiz: Why Your Core Matters More Than Your Wood

The "Federales" and the Price of Peace

"The Federales say they could have had him any day / They only let him go so long out of kindness, I suppose."

This is one of the most cynical lines in country music history. It suggests that the authorities weren't outsmarted by a brilliant bandit. They just didn't care. They let him run until he wasn't useful or entertaining anymore, then they let the desert finish him off.

It’s a commentary on fame. It’s a commentary on how we treat our icons. We let them destroy themselves for our entertainment, and when they finally drop, we act like it was inevitable.

The Confusion Over the Lyrics

Sometimes people mishear the words. They think Pancho was a "gentle man." He wasn't. The song says he was a "skinny lad." It emphasizes his vulnerability, not his strength.

And then there's the ending.

"The poets tell how Pancho fell / And Lefty’s living in a cheap hotel."

The poets (and the songwriters) get the glory. They get to tell the story. Pancho gets the legend. But Lefty? Lefty just gets to grow old. He’s the one who has to live with what he did—or didn't—do. In many ways, the Pancho and Lefty lyrics suggest that dying young in a hail of glory is a much better deal than surviving.

How to Listen to the Song Now

If you want to actually understand this piece of music, you have to stop looking at it as a history of the Mexican Revolution. It's a psychological profile of two different ways to fail.

- Pancho’s Way: You burn bright, you run fast, and you die before you get boring. You become a song.

- Lefty’s Way: You take the money. You move to Ohio. You grow old in a room that smells like stale cigarettes and regret.

Townes Van Zandt was a master of the "sad-happy" song. He wrote things that sounded beautiful but felt like a punch to the gut. This song is his masterpiece because it refuses to give you a hero. Pancho is a failure who died. Lefty is a failure who lived.

There’s no winner here.

Practical Insights for Songwriters and Fans

If you're looking at these lyrics to improve your own writing or just to appreciate the craft, take note of the "show, don't tell" approach. Townes never says "Lefty felt guilty." He says Lefty "kindly shook his head" when people asked about Pancho. That one gesture says more than a three-page diary entry ever could.

To truly appreciate the depth here, try these steps:

- Listen to the 'Heartworn Highways' version. This is Townes performing it in a kitchen, surrounded by friends and whiskey. It is the definitive version of the song's soul.

- Compare the verses. Notice how the first verse is about the mother, the middle verses are about the "action," and the final verse is about the aftermath. It’s a perfect three-act structure compressed into a few minutes.

- Look for the gaps. Townes leaves a lot of room for the listener to fill in the blanks. Did Lefty sell him out? Did the Federales actually know where he was? The ambiguity is why we’re still talking about it fifty years later.

The song doesn't provide answers because life doesn't provide answers. It just provides stories. And as the final lines remind us, we only tell the stories to "keep from sinking down."

Study the interplay between the harsh reality of "the cold wind" and the romanticized "polished steel." The power of the song lies in that friction. For those wanting to dive deeper into the outlaw country movement, researching the lives of Guy Clark and Steve Earle provides the necessary context for why these lyrics resonate with such authenticity. They lived the road that Townes warned us about.

Next Steps for the Deep Diver

💡 You might also like: Why the X Men Storm Action Figure Still Dominates Your Shelf (And Which One to Buy)

To fully grasp the impact of these lyrics, your next move should be to listen to Townes Van Zandt’s live album Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas. It contains the rawest delivery of the song ever captured. After that, read the biography To Live's to Fly: The Life and Times of Townes Van Zandt by John Kruth to see how much of Lefty was actually Townes himself.