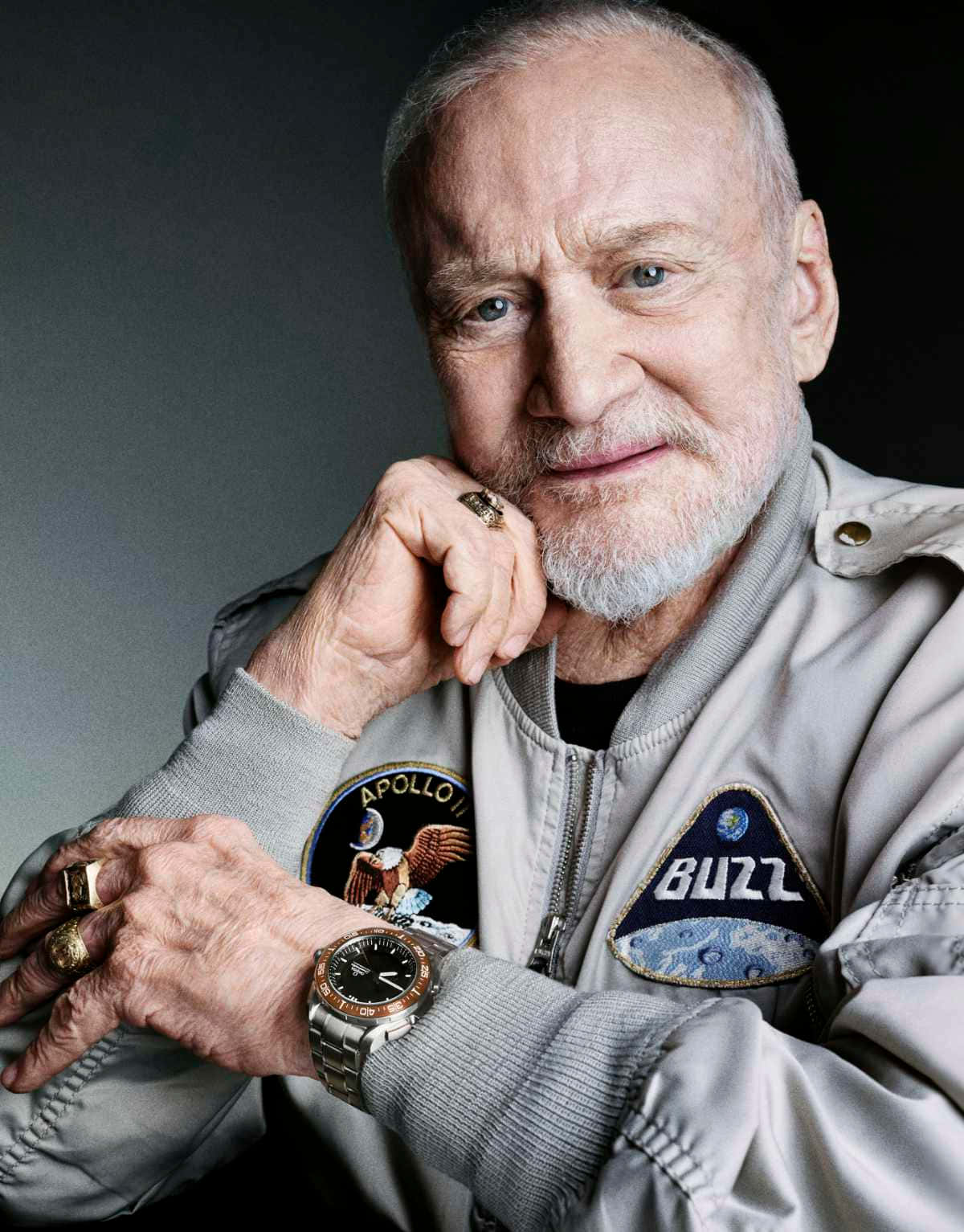

You’ve seen it. Everyone has. It’s that one image that basically defines the 20th century: a lone, white-suited figure standing in a vast, grey desolation, the blackness of space looming behind him. It’s the photo of Buzz Aldrin on the moon, and honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle it even exists in such high quality.

Most people look at that shot and see a hero. They see the "giant leap." But if you look closer—I mean really look at the reflection in Aldrin’s gold-plated visor—you’ll see the man who actually took the picture: Neil Armstrong.

There’s a weird irony here. Neil was the first human to ever step onto another world, yet there are almost no clear, still photos of him on the lunar surface. Why? Because Neil was the one holding the camera. He was the designated tourist photographer for the most expensive vacation in history.

The Camera That Shouldn't Have Worked

Space is a nightmare for photography. You’ve got no atmosphere, which means the sun is hitting your equipment with raw, unfiltered radiation. Temperatures swing from a bone-chilling -65°C in the shadows to a blistering 120°C in direct sunlight.

NASA didn't just grab a camera off a shelf at a drugstore (though they actually did that for John Glenn’s mission earlier on). For Apollo 11, they used a heavily modified Hasselblad 500EL. These "Hassies" were Swedish-made masterpieces. To survive the moon, they were painted silver to reflect heat and had all their internal lubricants removed because, in a vacuum, oil just boils off and ruins the lens.

👉 See also: Finding a Free PDF Document Reader That Doesn't Actually Sucking

- No Viewfinder: The astronauts couldn't look through a lens. Their helmets were too bulky.

- Chest Mounted: The camera was literally bracketed to the front of their suits.

- Blind Shooting: They had to aim by pointing their entire bodies. Imagine trying to frame a masterpiece while wearing a pressurized medieval suit of armor.

Neil Armstrong had to be a literal "point-and-shoot" expert. He practiced for months on Earth, wandering around in his suit, learning how to gauge the 60mm Biogon wide-angle lens by feel.

Why the Photo of Buzz Aldrin on the Moon is a Technical Freak Accident

The famous shot—officially known by its NASA ID AS11-40-5903—wasn't even a posed portrait. Not really. Aldrin was actually in the middle of a task. Neil just told him to "Hold it, Buzz," and Aldrin turned around.

If you look at his left arm, you can see his checklist sewn onto his glove. He was working. But the lighting was perfect. Because the moon has no atmosphere to scatter light, shadows are pitch black and highlights are blindingly bright. This is why conspiracy theorists always complain about the lack of stars.

Here’s the reality: The lunar surface is basically a giant, reflective concrete parking lot. To get a clear photo of a bright white spacesuit against that surface, you need a very fast shutter speed (usually 1/250th of a second). At that speed, the faint light of distant stars doesn't have enough time to register on the film. If Neil had exposed for the stars, Buzz would have looked like a glowing ghost in a white void.

The Face Behind the Gold

For decades, people thought you couldn't see Aldrin's face because of the gold sun visor. It’s a literal mirror. But in recent years, digital restoration and high-res scans of the original 70mm transparency have changed things.

If you zoom in and play with the levels, you can actually see Buzz's face. He’s looking toward Neil. Some people even say he looks like he's smiling, or at least intensely focused. It’s a haunting detail that makes the "spaceman" feel like a person again.

What Most People Miss in the Reflection

The visor reflection is the real "Easter egg" of history. When you "unwrap" that spherical reflection, you see a 360-degree view of the Sea of Tranquility.

- Neil Armstrong: He's standing there, legs spread for stability, the Hasselblad mounted to his chest.

- The Eagle: The Lunar Module looks like a spindly, gold-and-black insect in the background.

- The Earth: A tiny, fragile blue marble hanging in the blackness above the horizon.

- The Solar Wind Composition Experiment: A sheet of foil nearby, catching particles from the sun.

It’s basically the ultimate selfie, even if Neil isn't technically the subject.

The Mystery of the Missing Neil Photos

It’s kinda funny—and a little sad—that Buzz didn't return the favor. NASA was actually a bit annoyed when the film was developed back on Earth. They realized they had hundreds of great shots of Aldrin and almost none of the mission commander.

It wasn't malice. It was just a tight schedule. Every second on the moon was choreographed. They had experiments to set up, rocks to bag, and a clock ticking on their oxygen supply. Taking "tourist shots" of each other was low on the priority list.

There is one shot of Neil's back. One of him working near the lander. But the photo of Buzz Aldrin on the moon remains the definitive one because it captures the solitude. It makes the moon feel big and the human feel small.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this specific piece of history, don't just look at the blurry JPEGs on social media.

👉 See also: How Much is the Tesla Roadster: The Price of Waiting for a Rocket

- Check the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal: NASA hosts the full, unedited archives of every photo taken. Look for magazine "S" (the color film) to see the sequence.

- Study the "Reseau" Crosses: Notice those little black '+' marks on the photo? Those are etched into a glass plate (the Reseau plate) inside the camera. They helped scientists calculate distances and heights of objects in the photos later. If a photo doesn't have them, it's probably not an original lunar surface still.

- Visit the Smithsonian: The actual Hasselblad cameras used on the surface were mostly left behind to save weight for the return trip (they only brought back the film magazines). However, the "backup" and training cameras are often on display.

Understanding the photo of Buzz Aldrin on the moon isn't just about admiring a cool picture. It’s about realizing that two guys, 238,000 miles from home, managed to nail the lighting, focus, and composition on a camera they couldn't even see through. That's as much of a feat as the landing itself.