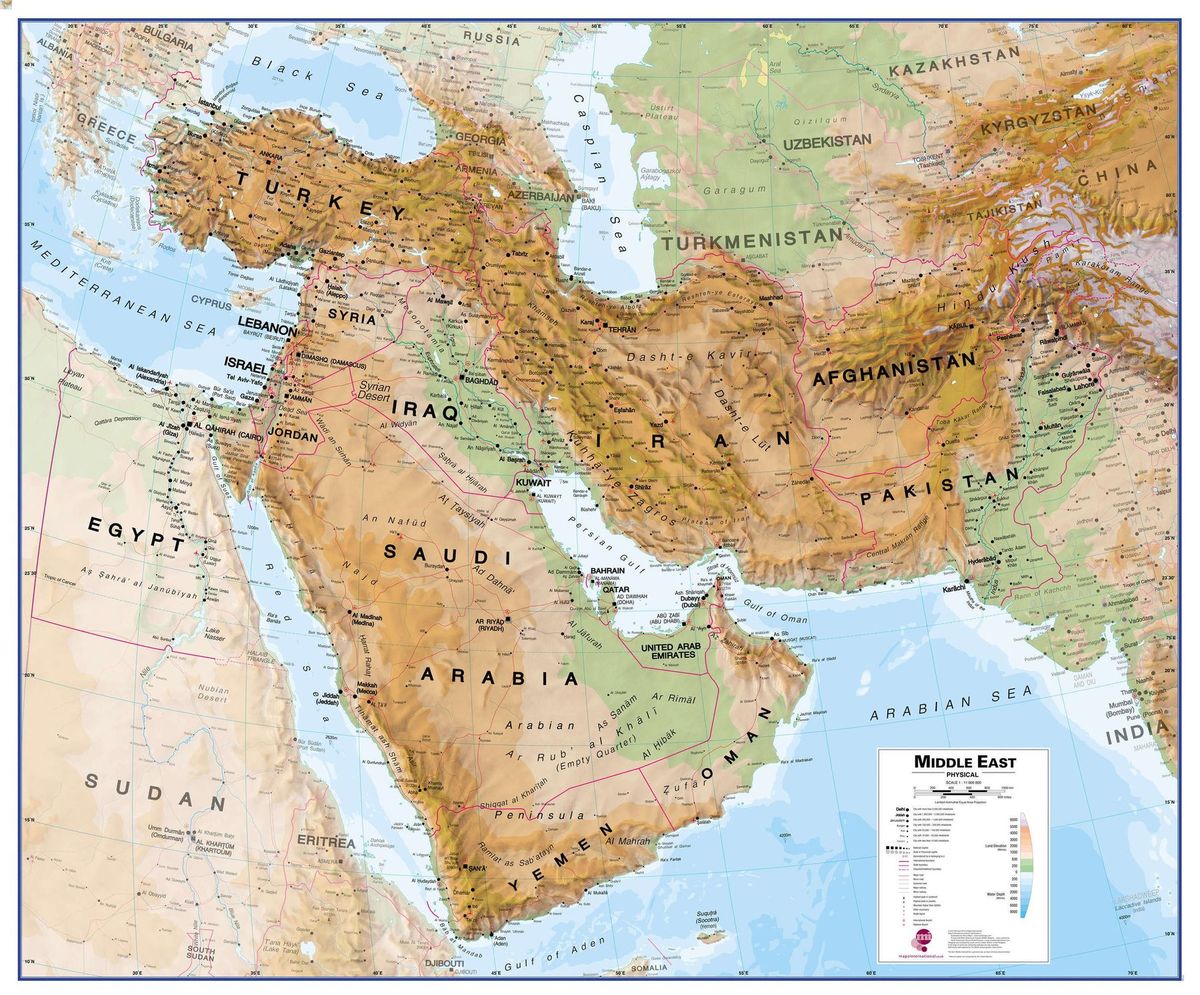

When you look at a map of the Middle East, it’s easy to get distracted by the straight lines of the borders. Most of those were drawn with a ruler by Europeans in the early 20th century. They don’t tell the real story. To understand why this region functions the way it does, you have to look underneath the political ink. The physical features of the middle east map are the real bosses here. They dictate where people live, how they move, and who gets rich.

It’s a rugged place. Basically, it’s a massive bridge between three continents, but it’s a bridge full of traps. You’ve got mountains that scrape the sky in Iran and depressions in the Levant that sit below sea level.

The Water Paradox: Rivers vs. Wadis

Water is everything. If you don't have it, you're dead. It's that simple. Most of the region is arid, but the few places that aren't have shaped human history for ten thousand years.

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers are the heavy hitters. They start in the highlands of Turkey and flow down through Syria and Iraq. These aren't just streams; they are the lifeblood of the "Fertile Crescent." When you see them on a physical map, they look like green veins cutting through a tan landscape. But here is the thing: they are unpredictable. Unlike the Nile in Egypt, which traditionally flooded with a sort of rhythmic reliability, the Tigris and Euphrates are temperamental. This forced ancient civilizations like the Sumerians to get really good at engineering early on.

Then you have the wadis. You’ll see these marked on detailed physical maps as dashed lines. They are dry riverbeds most of the year. But when it rains? They turn into flash-flood death traps in minutes. If you’re hiking in Jordan or Oman, a clear blue sky doesn't mean you're safe from a wadi flood happening miles away.

The Great Deserts: More Than Just Sand

People think the Middle East is just one big sandbox. It isn't. The Rub' al Khali, or the "Empty Quarter," is the most famous part. It covers about 250,000 square miles of the southern Arabian Peninsula. It’s huge. It’s also incredibly hostile. This isn't just "hot"; it's a place where the dunes can reach 800 feet high.

But then look at the Syrian Desert. It’s a mix of gravel plains and rocky plateaus. It’s not "pretty" sand; it’s hard, punishing ground. These deserts acted as massive natural barriers for centuries. They protected the interior of the Arabian Peninsula from invasion because, honestly, nobody wanted to march an army through that.

- The An Nafud in the north of Saudi Arabia is known for its reddish sands and sudden violent winds.

- The Dasht-e Kavir in Iran is a salt desert. It’s a crusty, marshy wasteland where the salt prevents almost any life from taking hold.

- The Negev in Israel is a "semi-arid" desert, showing how much variety exists in these "dry" zones.

Why Mountains Matter More Than You Think

If the deserts are the walls, the mountains are the fortresses. The physical features of the middle east map are dominated by massive tectonic activity.

The Zagros Mountains in western Iran are a perfect example. They run for about 990 miles. They aren't just hills; they are a series of parallel ridges that make travel from the Mesopotamian plains into the Iranian plateau incredibly difficult. This is why Iran has such a distinct cultural identity compared to its neighbors. The mountains kept people out.

To the north, the Elburz (Alborz) Mountains guard the Caspian Sea coast. This is where the map gets weird. Just a few miles from the salt deserts, you have lush, temperate rainforests on the northern slopes of the Elburz. It’s a complete 180-degree shift in ecology.

Then there’s the Taurus Mountains in Turkey. They separate the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian plateau. When you’re looking at a map, notice how the green coastal strips are squeezed thin against the sea by these ranges. It limits where you can build big cities.

The Dead Sea and the Great Rift

You can't talk about the physical layout without mentioning the Jordan Rift Valley. This is part of a massive tectonic tear in the Earth's crust that stretches all the way down into Africa.

At the bottom of this trench is the Dead Sea. It’s the lowest point on the Earth's surface—roughly 1,410 feet below sea level. The water is so salty you can’t sink. But more importantly, from a geographic perspective, this valley creates a natural north-south corridor. It’s been a highway for migrating birds and invading armies since the Bronze Age.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Kiribati: Why This Pacific Ocean Map Is Changing Everything We Know About Geography

Plateaus and the "High Ground"

Central Turkey and Iran are mostly high plateaus. The Anatolian Plateau in Turkey is a rugged, rolling landscape that stays quite cold in the winter. It’s a different world from the humid beaches of Antalya.

The Iranian Plateau is even more extreme. It’s surrounded by mountains on all sides, creating a "bowl" effect. This geography traps heat in the summer and cold in the winter. It also means that most of the water stays inside the bowl, forming those salt marshes I mentioned earlier.

The Impact of the Chokepoints

The map also shows three of the most important maritime chokepoints in the world.

The Strait of Hormuz is a tiny sliver of water between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Look at how narrow it is. About a fifth of the world's oil passes through there. If that physical feature didn't exist, the geopolitics of the last 50 years would look totally different.

Then there is the Bab el-Mandeb, the "Gate of Tears," at the southern end of the Red Sea. It’s the bottleneck between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Finally, you have the Suez Canal. While the canal is man-made, it exploits the Isthmus of Suez, a narrow strip of land that used to bridge the gap between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.

📖 Related: Consulate General of the United States: What Most People Get Wrong

Real-World Takeaways for Your Next Trip or Study

Understanding the physical features of the middle east map isn't just for geography bees. It has practical implications if you're traveling or doing business there.

- Elevation is everything. If you see mountains on the map, don't assume it's hot. Tehran or Amman can be freezing and snowy in January while the coast is mild.

- Distance is deceptive. 100 miles across a flat plain is easy. 100 miles through the Zagros Mountains can take all day.

- Coastal vs. Interior. Life on the Mediterranean coast of Lebanon or Israel feels "European" because the geography allows for trade and moderate weather. Move 50 miles inland, and the rain-shadow effect of the mountains turns everything into a different climate zone entirely.

The geography here isn't just a backdrop. It's the protagonist. The mountains aren't just "there"—they are barriers that have preserved languages and religions for millennia. The rivers aren't just water—they are the only reason millions of people can live in an otherwise uninhabitable space.

When you're looking at a map of the region next, ignore the countries for a second. Look at the brown ridges, the deep blue basins, and the vast tan expanses. That’s the real Middle East. It’s a landscape of extremes that forces everyone living there to adapt or disappear.

To truly master the layout of this region, start by identifying the three major "Highland" zones: the Anatolian Plateau, the Iranian Plateau, and the Ethiopian Highlands (which feed the Nile). Once you see those, the way the rivers flow and where the cities are built suddenly makes perfect sense. Use a topographic map rather than a political one next time you're planning a route or researching the area; the shadows of the mountains tell you more than the border lines ever will.