The air feels different when you’re standing at the base of that rock. It’s heavy. If you’ve ever actually been to the Macedon Ranges in Victoria, you know the sensation—it's this weird, magnetic pull mixed with a sudden urge to check your watch. Most people arrive at the site because of the story. They’re looking for the ghosts of schoolgirls in white muslin dresses. They want to know if Miranda ever came back.

But here’s the thing. Picnic at Hanging Rock is a masterpiece of blurred lines. It’s a story so deeply embedded in the Australian psyche that half the people who visit the site genuinely believe they are walking on a crime scene. It isn't a crime scene. Well, not a real one. But it feels like one, and that’s exactly why we’re still talking about it decades after Joan Lindsay first put pen to paper.

The Myth of the "True Story"

Let's clear the air immediately. There is no police record of three girls and a teacher vanishing from Appleyard College on Valentine’s Day, 1900. It didn't happen. Honestly, it’s a testament to Joan Lindsay’s writing that she managed to gaslight an entire nation into believing a work of fiction was a historical tragedy. She was incredibly vague about the book's origins, famously stating in the preface that whether the story is fact or fiction "my readers must decide for themselves."

People decided they wanted it to be true.

🔗 Read more: DEA Airport Searches Suspended: What Really Happened to Those Jetway Shakedowns

Even now, the local visitor center has to deal with tourists asking where the girls went. The confusion stems from Lindsay's masterful use of "found footage" style narrative before that was even a thing. She used fake newspaper clippings and a very specific, stiff Edwardian tone that made the whole thing feel like a dusty archive pulled from a basement.

The real Hanging Rock—geologically known as Mount Diogenes—is a mamelon, a rare volcanic formation. It’s about 6.25 million years old. It’s a place of immense significance to the Wurundjeri, Taungurung, and Dja Dja Wurrung peoples, who lived there for thousands of years before Europeans arrived and started losing their fictional children in the crevices. When you look at the rock through that lens, the "mystery" of a few vanished colonial girls feels almost like a modern layer of paint on an ancient, much more complex canvas.

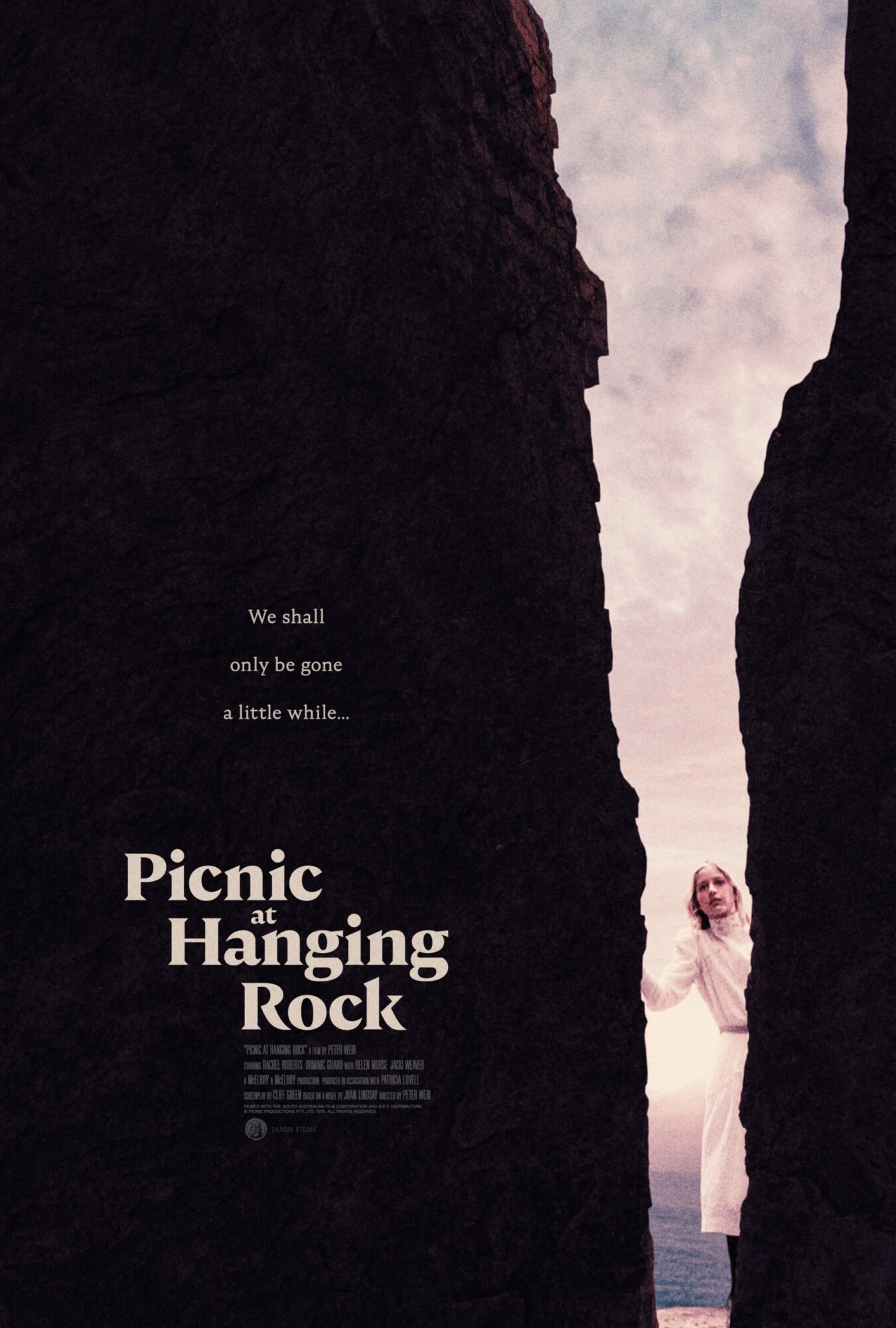

What Peter Weir Did to Our Collective Memory

If the book planted the seed, the 1975 film by Peter Weir turned it into a forest. It’s hard to overstate how much that movie changed Australian cinema. Before Weir, Aussie movies were often rugged, loud, and "ocker." Then came Picnic at Hanging Rock with its soft focus, Panpipes, and that haunting, ethereal light.

Weir used actual physical tricks to mess with the audience. He told his cinematographer, Russell Boyd, to use bridal veil netting over the camera lenses to give the film that hazy, dreamlike quality. It worked. You don't just watch the movie; you inhale it.

The Music and the Silence

Bruce Smeaton’s score, featuring the pan flute of Gheorghe Zamfir, is iconic, but the silence is better. Think about the scene where the girls begin to climb. The sound of the wind, the flies, the scraping of leather boots on stone—it’s visceral. It creates a sense of dread that has nothing to do with jump scares and everything to do with the Australian bush itself. The bush is the antagonist. It’s indifferent. It’s old. It doesn't care if you're wearing a corset or if you have a math lesson at four o'clock.

The "Final Chapter" Controversy

For years, there was a rumor. A secret.

Joan Lindsay’s original manuscript actually had a final chapter—Chapter 18—that explained everything. Her editor, Sandra Forbes, suggested she cut it before publication in 1967. They wanted to keep the mystery alive. It was the smartest editorial move in literary history.

In 1987, after Lindsay died, The Secret of Hanging Rock was finally published, revealing that missing chapter. If you’re a fan of the supernatural, you might like it. If you prefer the haunting ambiguity of the film, you’ll probably hate it.

The chapter describes a "hole in space." Basically, a time warp. Miranda and the others undergo a sort of physical transformation—shedding their corsets (which symbolize the constraints of Victorian society) and essentially turning into lizards or spirits to pass through a crack in the rock. It’s weird. It’s very 1960s psychedelic. Honestly, it’s a bit of a letdown compared to the terrifying "nothingness" of the published version. The unknown is always scarier than a time-traveling crevice.

Why the Rock Still Draws a Crowd

Hanging Rock isn't just a filming location. It’s a massive tourist draw for the Macedon Ranges. But visitors should go prepared. This isn't a manicured park. It's steep. It's rugged.

- The Hike: It takes about 40 to 50 minutes to get to the summit. It’s not Everest, but it’ll wind you.

- The Views: You get a 360-degree look at the Victorian countryside. It’s stunning.

- The Wildlife: Kangaroos and wallabies are everywhere, especially at dusk. Just don't try to pet them.

- The Vibes: Even if you don't believe in ghosts, the rock formations (like the "Hanging Rock" itself, which is a boulder wedged between two others) are genuinely imposing.

There is a strange phenomenon reported by hikers—clocks stopping. This actually happens in the book and the movie. Skeptics say it’s the high iron content in the volcanic rock interfering with mechanical or electronic devices. Believers say it’s something else. Either way, check your iPhone battery before you head up.

The Cultural Weight of the Corset

A lot of academics have lost sleep over Picnic at Hanging Rock. They see it as a metaphor for the British Empire’s failure to "tame" the Australian landscape. The girls are dressed in white, pristine, restrictive clothing. They are the pinnacle of European "civilization." The Rock is the antithesis of that.

When the girls remove their shoes and stockings to climb higher, they are shedding their European identity. They are being consumed by a landscape that doesn't recognize their rules. It’s a survival story where nobody survives, at least not in the way they started.

This theme is why the story keeps getting remade. We had the 2018 miniseries starring Natalie Dormer, which took a much more "prestige TV" approach. It was more colorful, more aggressive, and leaned harder into the dark past of Mrs. Appleyard. While it didn't capture the lightning-in-a-bottle magic of the 1975 film, it proved that the appetite for this specific mystery is bottomless.

Visiting Hanging Rock Today: A Reality Check

If you're planning a trip, don't expect a somber, silent experience. It’s a popular spot for families, picnickers (ironically), and even races. The Hanging Rock Races are a massive deal in the local sporting calendar.

Wait, what about the girls?

The local community has a bit of a love-hate relationship with the myth. On one hand, it brings in the tourist dollars. On the other, the management has to constantly remind people that the site is a place of ecological and Indigenous importance, not just a movie set.

If you go, respect the path. The rock is fragile. Erosion is a real thing, and thousands of boots every weekend take their toll. Also, bring water. The Victorian sun is no joke, and unlike the girls of Appleyard College, you can't just disappear into a crack in the space-time continuum when you get dehydrated.

What We Get Wrong About the Ending

People often ask "Who killed them?" or "Who took them?"

That’s the wrong question. In the world of Picnic at Hanging Rock, the "who" doesn't matter. The "what" is the land itself. The story isn't a whodunnit; it’s a "nature-dunnit." It’s about the realization that humans are small. We like to think we’ve conquered the world with our maps and our clocks and our schools, but a 6-million-year-old rock suggests otherwise.

Actionable Steps for Your Own "Picnic"

If you’re heading to the Macedon Ranges to see the site for yourself, here is how to do it right:

- Check the Weather: The Rock can be dangerous in high winds or extreme heat. Check the Parks Victoria website before you drive out.

- Go Early: To catch that "eerie" feeling without five hundred schoolkids around, get there right when the gates open (usually 9:00 AM).

- Visit Woodend: This is the nearby town. It’s charming, has great bakeries, and gives you a feel for the "gateway" to the wilderness that the characters would have experienced.

- Read the Book First: Or at least watch the 1975 film. The experience of the climb is 100% better when you know the lore.

- Ditch the "Found Footage" Expectation: Remember it's fiction. Enjoy the geology and the history of the First Nations people who were there long before Joan Lindsay had an idea for a story.

The mystery of Hanging Rock persists because it taps into a universal fear: the fear of the unknown. We hate not having answers. We hate the idea that someone can just... walk away and never be seen again. But as long as that rock stands, and as long as we keep watching Miranda disappear into the shadows, the legend stays alive. It’s a ghost story where the ghost is the mountain.