You’re standing on a patch of dry land, looking at a brown lawn or a thirsty garden, and thinking about the water sitting hundreds of feet below your boots. It’s right there. But getting to it usually involves a massive rig that looks like an oil derrick, costs five figures, and tears up your entire driveway. That is exactly why the portable well drilling machine has become such a massive deal for homesteaders and DIYers lately. It promises independence. It promises water without the $15,000 bill from a commercial driller.

But honestly? Most of the stuff you see online about these "easy-to-use" rigs is kinda misleading.

Drilling a hole in the dirt isn't the same as drilling a hole in a 2x4. You aren't just fighting gravity; you're fighting hydrostatic pressure, collapsing sands, and the literal bedrock of the earth. I’ve seen people buy a cheap $800 kit off a random website only to have the motor burn out thirty feet down because they hit a layer of clay that felt like wet concrete. If you want to actually reach an aquifer, you have to understand the physics of the hole.

The Reality of Small-Scale Drilling

There is a huge difference between a "post-hole" auger and a legitimate portable well drilling machine.

A lot of people get these confused. An auger just screws into the dirt. It’s great for fence posts or maybe a very shallow "bored" well in areas with a high water table, like parts of Florida or the Mississippi Delta. But if you're trying to get 100 feet down to hit clean, filtered water, you need a rig that uses fluid. This is called mud rotary drilling.

Basically, you pump a mixture of water and bentonite clay down through the middle of your drill pipe. It shoots out the bit at the bottom, cools it down, and carries the "cuttings" (the dirt and rock you’re grinding up) back to the surface. Without this fluid, your hole will just collapse on itself the second you pull the pipe out. It’s a messy, wet, and rhythmic process. It’s also the only way a machine small enough to fit in the back of a pickup truck can actually get the job done.

🔗 Read more: Apple AirPods Third Generation: Why They’re Still The Best Middle Ground

Why Weight Matters (But Not Why You Think)

In the world of heavy machinery, weight is usually your friend. With a portable well drilling machine, you're trying to balance two things: "downward pressure" and "portability."

If the rig is too light, the bit will just spin on top of a hard rock layer without biting in. You’ll be there for six hours and gain two inches. On the flip side, if it’s a 500-pound beast, you aren't moving it into your backyard without a tractor.

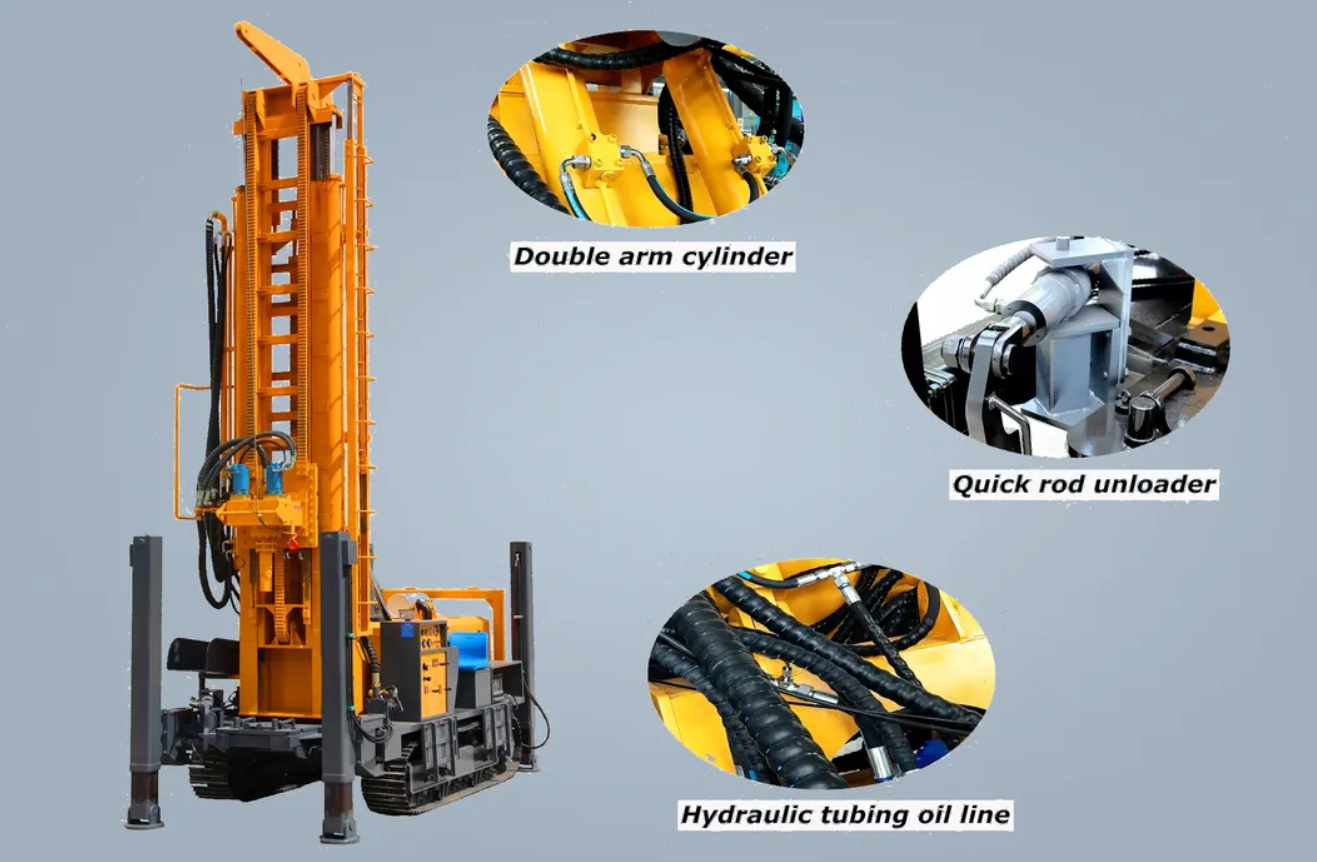

The best portable designs—like those from DeepRock or Lone Star Drills—solve this by using a winch or a hydraulic pull-down system. This lets a relatively light machine "push" against its own frame or anchors to get that bit moving through tough strata.

Mud Rotary vs. Percussion: Which One Wins?

You’ll see two main types of portable rigs for sale.

Mud rotary is the king of the DIY market right now. It’s relatively fast. It handles sand, silt, and soft rock like a champ. Companies like Hydra-Drill have been selling these for decades. They look a bit like a giant ladder with a motor on a slide. They’re efficient.

Then you have percussion or "cable tool" drilling. This is the old-school way. You’re essentially dropping a heavy, pointed weight over and over again to smash the rock. It’s slow. It’s loud. It’s basically a rhythmic "thump... thump... thump." But if you are in an area with nothing but solid granite? A small rotary rig might just sit there and smoke. Cable tools don't care about hardness; they just smash.

Most homeowners go with rotary because it’s cleaner and the equipment is more widely available. Just know your geology before you click "buy." Check the USGS (United States Geological Survey) groundwater maps for your specific county. If your neighbors all have 400-foot wells drilled through solid limestone, a portable gas-powered rig is going to have a very bad day.

What Nobody Tells You About the "Hidden" Costs

The machine itself is just the beginning.

Let's say you buy a mid-range portable well drilling machine for $3,000. You think you're done, right? Nope. You need the "drill string"—that’s the actual pipe. Most rigs only come with about 50 feet. If your water is at 120 feet, you're buying another $800 in pipe.

Then there’s the mud pump. You need a high-trash pump that can handle sandy water without seizing up. Don't use a standard clear-water pump; the grit will destroy the seals in twenty minutes.

- Bentonite Clay: You’ll need bags of this stuff to keep your hole open.

- Well Casing: This is the permanent PVC pipe that stays in the ground.

- Well Screen: The specialized slotted pipe at the bottom that lets water in but keeps sand out.

- The Pump: Once the hole is drilled, you still need a submersible pump to get the water to your house.

Honestly, by the time you're done, you've probably spent double the price of the machine. It’s still cheaper than hiring a pro, but it's not the "weekend project for $500" that some YouTube videos claim it is.

The Legal Minefield

This is where things get sticky.

In many states, like California or New Jersey, you can't just poke a hole in the ground because you feel like it. They have strict "well driller" licensing requirements. Why? Because if you drill a hole and don't seal it correctly, you can contaminate the entire aquifer for everyone in your town.

Surface runoff—think pesticides, motor oil, animal waste—can run straight down your poorly constructed well and into the drinking water.

Before you start, call your local health department. Ask about "homeowner's exemptions." Some places allow you to drill your own well for irrigation but not for drinking water. Others require a permit and a final inspection by a pro. Don't skip this. A "wildcat" well can lead to massive fines and a mandatory "capping" order that costs thousands to execute.

The Art of Finding Water

You’ve got the machine. You’ve got the permits. Now, where do you drill?

Some people swear by dowsing or "water witching" with copper rods. Science says it’s the ideomotor effect (unconscious muscle movements). I’ve seen it work, and I’ve seen it fail spectacularly. A better bet is looking at the local flora. Willows, cottonwoods, and lush green patches in a dry field are nature's neon signs for shallow water.

Expert drillers also look at "offset wells." If your neighbor to the north hit water at 80 feet and your neighbor to the south hit it at 90, there's a pretty high statistical probability you'll find it somewhere in that range.

Engineering a Successful Bore

When you finally fire up your portable well drilling machine, the biggest mistake you can make is rushing.

If you force the bit, you’ll deviate. Your hole won't be straight. A crooked hole is a nightmare because when you try to drop your permanent casing down, it’ll get stuck halfway. Now you have a useless hole and a hundred dollars worth of PVC jammed in the earth.

Keep your RPMs steady. Watch the color of the "return" water. If the water suddenly disappears and doesn't come back up the hole, you've hit a "void" or a highly porous layer. This is where you have to dump in "lost circulation material"—sometimes even shredded newspaper or specialized pellets—to plug the leak so your fluid can start circulating again.

It’s a game of patience. It’s about feeling the vibrations in the handle and listening to the engine.

Is It Actually Worth It?

For most people? Probably not. It’s back-breaking labor. It’s muddy. It’s frustrating.

But for the homesteader off the grid, or the farmer who needs a back-pasture well for cattle, a portable well drilling machine is a literal lifesaver. It provides a level of self-sufficiency that you just can't get any other way. There is a profound sense of satisfaction when that muddy water finally clears up and starts flowing cold and fresh from a hole you made yourself.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Driller

If you are serious about doing this, don't just go out and buy a machine today. Start with the data.

- Check the Geology: Go to the USGS Groundwater Data portal. Find your specific location and see how deep the "static water level" is. If it's deeper than 200 feet, most portable rigs will struggle.

- Rent Before You Buy: Many local equipment yards have small towable rigs. Spend $300 to rent one for a day to see if you can even handle the physical demands of the job.

- Source Your Mud: Find a local supplier for drilling bentonite. Don't try to use backyard clay; it doesn't have the same swelling properties and won't protect the borehole walls.

- Plan the Casing: Decide on your well diameter. Most portable rigs are designed for 2-inch or 4-inch wells. A 4-inch well is better because it allows for a standard submersible pump, whereas 2-inch wells usually require a "jet pump" on the surface, which is less efficient.

- Sanitize Everything: Once you hit water, you have to "shock" the well with chlorine to kill any bacteria introduced during the drilling process. Get a water testing kit from a lab—don't just taste it and assume it's fine.

Drilling is one part mechanics and two parts intuition. Respect the ground, follow the regulations, and be prepared to get very, very dirty. If you do it right, you'll have a source of water that lasts for decades. If you do it wrong, you just have a very expensive, very deep hole in your yard. Choose your rig based on your soil, not just the price tag.