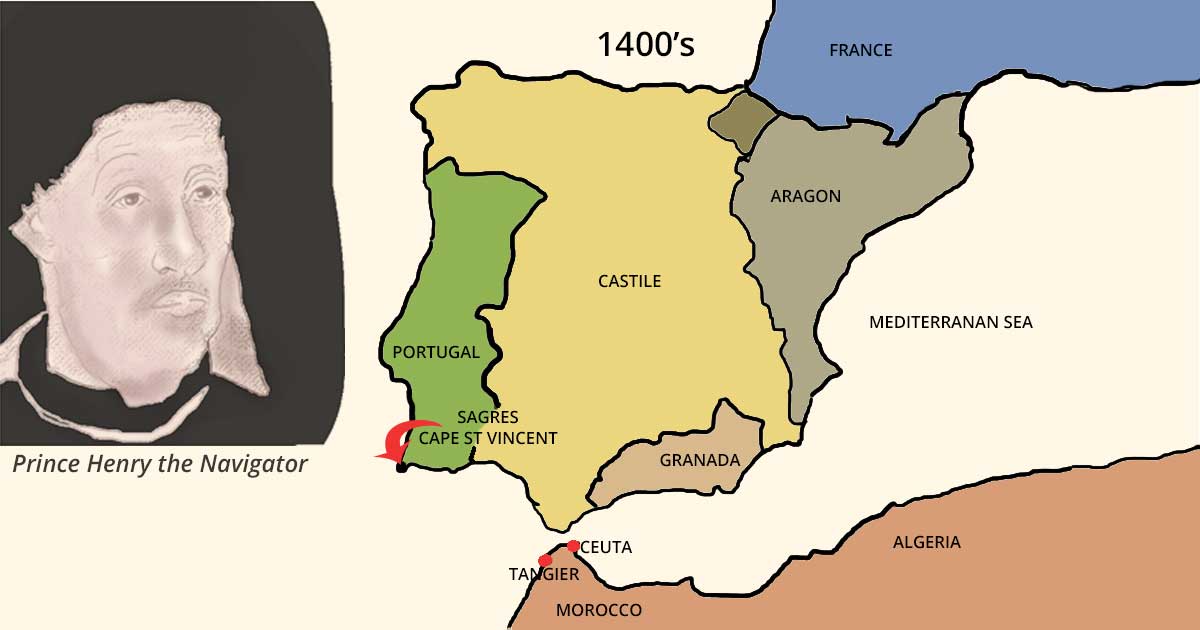

He never actually went on the voyages. Honestly, that’s the first thing you have to wrap your head around if you want to understand Prince Henry the Navigator. People imagine this salt-crusted captain standing at the prow of a ship, squinting into the horizon of the "Sea of Darkness." In reality, Infante Henrique of Portugal was more like a venture capitalist or a high-level project manager than a sailor. He spent most of his time on land, specifically at the windswept tip of Portugal in Sagres, obsessing over maps and money.

It’s kinda wild how history remembers him. We give him this grand nickname—"The Navigator"—but that wasn't even a thing until German and British historians started using it in the 19th century. To his contemporaries, he was a royal prince of the House of Aviz, a crusader, and a man who was deeply, perhaps even dangerously, obsessed with finding a way around the coast of Africa. He wasn't just looking for adventure. He wanted gold. He wanted to find the mythical Christian king Prester John. He wanted to outflank the Muslim powers that controlled the trans-Saharan trade routes.

The Myth of the School of Sagres

You’ve probably heard about the "School of Sagres." The story goes that Henry gathered the world's best astronomers, cartographers, and shipbuilders in a sort of 15th-century NASA facility to solve the problem of Atlantic navigation.

Is it true? Well, mostly no.

While Henry definitely sponsored mapmakers like Jehuda Cresques and brought in experts to help refine the caravel, there wasn't a formal "university" in the way we think of it. It was more of an informal hub. A tech incubator, maybe. He was the patron. He had the Order of Christ's treasury at his disposal—which was basically a massive pile of Crusader wealth—and he used it to fund experimental ship designs.

Before Henry, European ships were heavy and clunky. They used square sails that were great if the wind was behind you, but useless if you had to sail against it. Henry's teams popularized the lateen sail. These triangular sails allowed ships to "tack" or sail at an angle into the wind. Without this specific tech upgrade, the Age of Discovery simply wouldn't have happened. The Portuguese would have remained stuck, hugging the coast of Morocco forever.

Why Everyone Was Terrified of Cape Bojador

To understand why Prince Henry the Navigator is a big deal, you have to understand Cape Bojador. In the 1400s, this spot on the Western Sahara coast was the edge of the world. Sailors called it the "Point of No Return."

The legends were terrifying. People believed the ocean boiled there. They thought the sun was so close to the earth that your skin would turn black instantly. They thought sea monsters lived in the shallows. But the real problem was the geography. The currents at Bojador are incredibly strong and move southward, and the winds blow the same way. If you sailed past it in a traditional ship, you couldn't get back. You’d be trapped, drifting south into the unknown until you starved.

Henry sent fifteen expeditions to pass that cape between 1424 and 1434. Every single one turned back. His captains were terrified. They made excuses. They blamed the "frightful seas."

Finally, Gil Eanes, a squire in Henry’s household, made the breakthrough in 1434. He didn't find monsters. He found a relatively calm sea and some desert plants. He brought back a "St. Mary’s Rose" to prove he’d landed. This moment changed everything. It broke the psychological barrier of the medieval mind. Once the "boiling sea" was proven to be a myth, the floodgates opened.

The Darker Side of the Enterprise

We can't talk about Henry without talking about the human cost. This is where the "noble explorer" narrative falls apart. Henry’s expeditions weren't just about maps; they were the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade.

In 1441, Antão Gonçalves and Nuno Tristão brought the first captives from the African coast back to Portugal. Henry didn't just allow this; he took a 20% cut (the quinto) of all profits. By the 1450s, the Portuguese were kidnapping or trading for nearly a thousand people every year.

It’s a complicated legacy. On one hand, you have this intellectual curiosity and the advancement of maritime science. On the other, you have the institutionalization of human trafficking. Chroniclers like Gomes Eanes de Zurara wrote about these events in the Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea. Zurara describes the scenes of families being separated with a mix of pity and religious justification, claiming these people were being "saved" by being brought into the Christian fold. It’s heavy stuff, and it’s a part of Henry’s story that is often glossed over in older textbooks.

The Science of the Stars

Henry knew that to go further, his captains needed to stop relying on landmarks. They needed the stars.

👉 See also: A Frame House Design: Why These Pointy Structures Are Actually Getting Practical Now

Under his patronage, Portuguese mariners started using the astrolabe and the quadrant. These weren't new inventions—the Greeks and Arabs had used them for centuries—but Henry’s guys adapted them for use at sea. They started recording the "altitude" of the North Star to figure out their latitude.

- They created regimentos, which were basically "how-to" guides for celestial navigation.

- They mapped the Volta do Mar, a sailing technique that involved sailing far out into the Atlantic to catch the trade winds that would bring them back home.

- They transitioned from "dead reckoning" (guessing based on speed and direction) to mathematical navigation.

This shift was massive. It meant a captain could lose sight of land for weeks and still know, roughly, where he was on a map. It’s the direct ancestor of the GPS in your pocket.

Financing the Great Unknown

How did he pay for all this?

Exploration is expensive. Henry was the Grand Master of the Order of Christ. This was the successor to the Knights Templar in Portugal. He had access to immense land holdings and rents. But he was also a savvy businessman. He secured a royal monopoly on the trade of tuna, salt, and even soap in certain regions.

He was constantly broke, though.

Despite his monopolies, the cost of losing ships and funding years of failed voyages put him in constant debt. He was a man who played the long game. He wasn't looking for a quick return on investment; he was looking to build a maritime empire. He died in 1460, decades before Vasco da Gama reached India or Columbus hit the Caribbean, but the infrastructure he built made those trips possible.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think Henry was trying to prove the Earth was round. Honestly? Everyone in the 15th century who was educated already knew the Earth was a sphere. That’s a later myth.

The real mystery Henry was trying to solve was the size of Africa. He had no idea how far south it went. Some maps at the time suggested Africa curved back and joined with Asia, making the Indian Ocean a giant lake. Henry’s persistence proved that you could actually get around the continent.

Another misconception is that he was a lonely hermit. While he was definitely a bit of a "monk-prince" who never married, he was deeply involved in the politics of the Portuguese court. He participated in the disastrous siege of Tangier in 1437, which resulted in his younger brother, Fernando, being taken hostage and eventually dying in a Moroccan prison. That failure haunted him for the rest of his life.

Why This History Still Matters Today

Prince Henry the Navigator represents the moment the world started to shrink. Before him, different civilizations operated in silos. After him, the Atlantic became a highway.

We see his influence in:

- Global Trade: He set the template for the colonial trading post system.

- Navigation Tech: The transition to data-driven travel started in his workshops.

- Cultural Exchange: For better or worse, he initiated the permanent contact between Europe, Africa, and eventually the Americas.

He was a man of contradictions. A crusader who studied Islamic charts. A prince who spent his life around sailors. A man who sought God but found gold and slaves. You can't understand the modern world without looking at the maps he helped draw.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the world of 15th-century exploration, stop reading general summaries and look at the primary sources.

- Read the Chronicles: Check out Gomes Eanes de Zurara’s Chronicles of Guinea. It’s biased, sure, but it’s the closest thing we have to a contemporary account of Henry's life and the "discoveries."

- Visit the Monument to the Discoveries: If you ever find yourself in Lisbon, go to the Belém district. The Padrão dos Descobrimentos is a massive stone ship on the water’s edge with Henry at the front. It gives you a sense of the scale of Portuguese ambition.

- Study the Caravel: Look at the engineering of the caravel ship. Understanding the physics of the lateen sail helps you appreciate why they were finally able to beat the winds at Cape Bojador.

- Analyze the Map of Fra Mauro: This 1450 map is a snapshot of what the world looked like to experts just before the "big" discoveries. You can see the Portuguese influence starting to creep down the African coast.

The legacy of Henry isn't just a list of dates. It's a story of what happens when human curiosity is backed by significant capital and a complete disregard for the status quo. It’s about the shift from the medieval to the modern, written in salt and parchment.