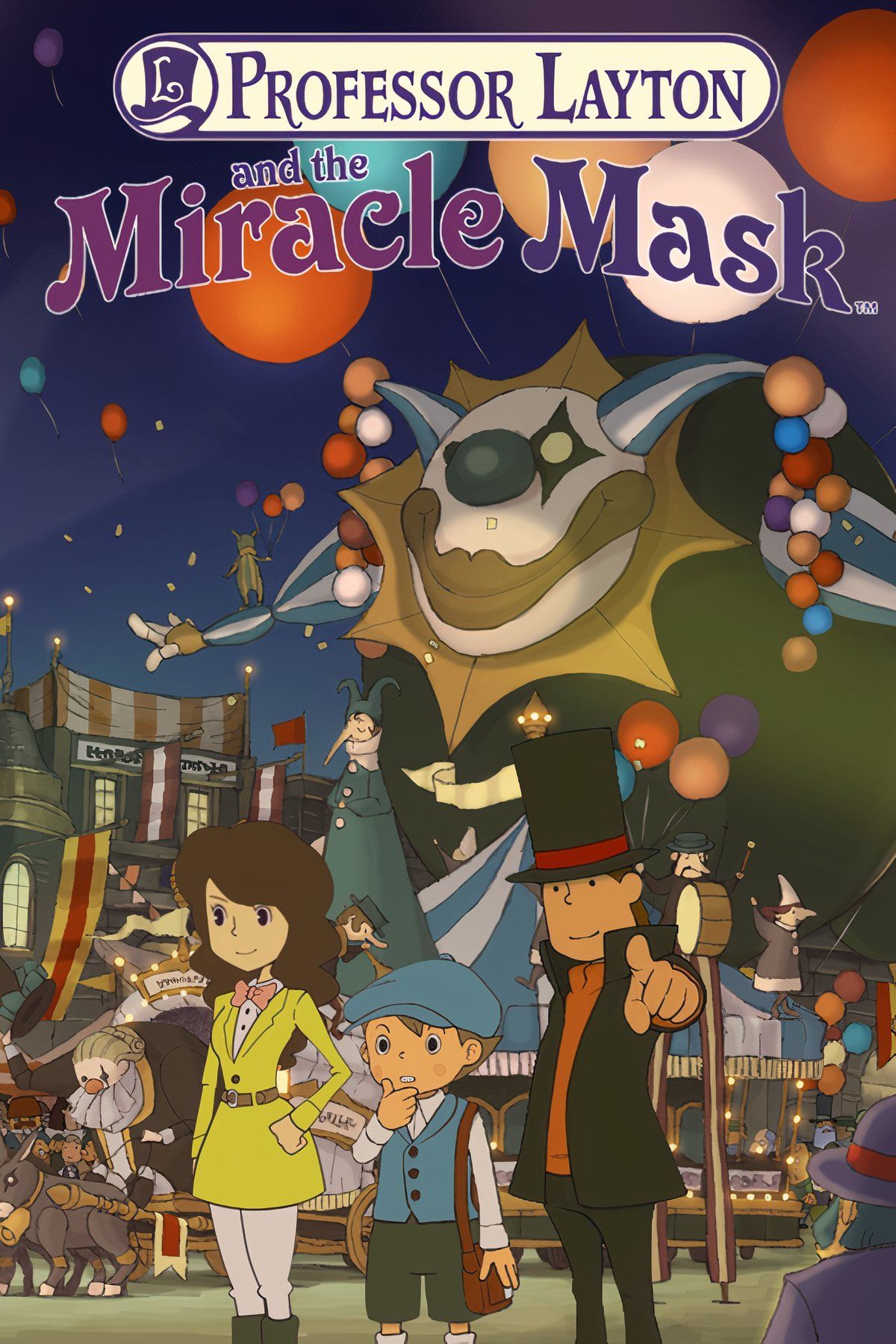

Honestly, it’s hard to believe it’s been well over a decade since Hershel Layton first stepped into the neon-soaked streets of Monte d’Or. Most people remember Professor Layton and the Miracle Mask as "the one where the graphics changed." While that’s technically true, it's a bit of a disservice to what this game actually did for the series.

It wasn't just a hardware jump. It was a massive gamble by Level-5.

In early 2011, the Nintendo 3DS was launching in Japan, and Akihiro Hino—the mastermind behind the series—was determined to make the Professor the face of the new handheld. The game actually started production as a standard 2D DS title. You can still find old development screenshots of the 2D sprites if you dig deep enough into the archives of E3 2010. But once Hino saw what the 3DS could do, he reportedly ordered a total scrap-and-rebuild.

💡 You might also like: Clair Obscur Isle of Eyes: The Secret Reward Most Players Miss

He wanted something "no one had ever seen before." That’s a bold claim for a game about a guy in a top hat doing math problems.

The Monte d’Or Mystique and the Masked Gentleman

The story kicks off with a letter from an old friend, Angela Ledore. She’s worried about a figure called the Masked Gentleman who is performing "dark miracles" in the middle of a desert city. If that sounds like Las Vegas, it basically is.

Monte d’Or is a drastic departure from the sleepy, foggy European villages of previous games. It’s bright. It’s loud. It’s full of suspicious-looking clowns.

But the real heart of the narrative isn't the present-day mystery; it’s the flashback sequences. This is where we meet 17-year-old Hershel. If you’ve only ever known the Professor as the poised, tea-drinking archeologist, seeing him as a goofy high schooler with a messy ponytail is a trip. We finally get the origin of his obsession with puzzles, and it’s tied directly to his best friend, Randall Ascot.

The game does this weird, effective thing where it runs two timelines at once. You’re investigating the Masked Gentleman in the present, but every few chapters, you’re thrown back eighteen years into the past to explore Azran ruins. It builds this incredible tension because you know something terrible happened to Randall, but the game makes you wait until the final hours to see how it all connects.

Why the Gameplay Shift Was So Controversial

Let’s talk about the magnifying glass. For four games, we just tapped the screen. Simple. Intuitive.

In Professor Layton and the Miracle Mask, Level-5 moved the investigation to the top screen. You use the stylus to slide a cursor around the bottom screen, and when it turns orange, you tap. Some fans hated this. It felt like an extra step that didn't need to exist.

The Evolution of Puzzles

Despite the interface changes, the puzzles—overseen by the late Akira Tago—remained top-tier. There are 150 in the main story, and the 3D depth actually added something new. You weren't just looking at flat images; you were rotating 3D corncobs to guide ladybugs and tilting the console to solve environmental riddles.

- Toy Robot: This minigame was surprisingly deep. You have to navigate a maze in specific three-step movements.

- One-Stop Shop: A shelf-stacking game where you have to trick customers into buying everything. It’s way more addictive than it sounds.

- The Bunny Show: You basically become a rabbit trainer. Luke spends half the game talking to a bunny to get it ready for the circus.

One thing people often forget is that this was the first Layton game to offer 365 days of downloadable content. One new puzzle every day for a year. That’s a staggering amount of content that most modern mobile games wouldn't even attempt today.

Breaking the 2D Tradition

The jump to 3D models was polarizing. The 2D art by Takuzō Nagano was iconic—it looked like a moving storybook. Moving to polygons made the characters look a little "crunchy" in certain lights.

However, it allowed for the series' first-ever action sequences. Remember the horse chase? Or the top-down dungeon crawling in the ruins? Those would have been impossible, or at least very clunky, with 2D sprites. It turned Layton from a static visual novel into a "game" in the more traditional sense.

What Most People Miss About the Ending

The finale of Professor Layton and the Miracle Mask is essentially a giant setup for The Azran Legacy. If you play this as a standalone, the ending feels a bit like a "to be continued" cliffhanger.

We learn that the Targent organization—and its leader Leon Bronev—have been pulling strings in the background. It recontextualizes everything we thought we knew about the Azran civilization. It’s not just about a mask; it’s about a global conspiracy that spans the entire prequel trilogy.

How to Experience it Today

If you’re looking to play it now, you’ve got a few hurdles. The 3DS eShop is long gone, so you’re looking at tracking down a physical cartridge. Prices vary, but it’s usually one of the more affordable Layton titles compared to the rare DS ones.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans:

- Check the "Plus" Version: If you have access to a Japanese 3DS, look for Kiseki no Kamen Plus. It added extra cutscenes and puzzles that weren't in the original launch.

- Play in Order: Don't start here. Play Professor Layton and the Last Specter and watch the movie The Eternal Diva first. The emotional payoff with Emmy and Descole is much stronger that way.

- Use Your Hint Coins Wisely: The "ruins" section in Chapter 7 is notoriously stingy with hint coins. Don't blow them all on the early-game math riddles.

This game remains a fascinating bridge between the old-school DS era and the modern, high-production Layton games we see today. It’s messy, it’s experimental, but it has more heart than almost any other entry in the series.

Stay curious. A true gentleman leaves no puzzle unsolved.