Hollywood did a number on our collective memory. You’ve seen the trope: the "hooker with a heart of gold" in a red sequined dress, leaning over a balcony in a dusty saloon. It’s a clean, almost romanticized image. But the reality of prostitution in the Wild West was gritty. It was a business. It was survival. Honestly, for many women moving across the 100th meridian in the mid-to-late 19th century, it was the only way to keep from starving in a world that didn't give them many options.

The West was overwhelmingly male. In the early days of the California Gold Rush or the Comstock Lode in Nevada, the ratio of men to women was often 20 to 1. Sometimes it was even higher. Where there is a massive gender imbalance and a lot of liquid cash from mining or cattle, you’re going to find a thriving sex trade. It wasn't just a "side effect" of frontier life; it was often the economic engine that kept these boomtowns running.

The Hierarchy of the "Soiled Doves"

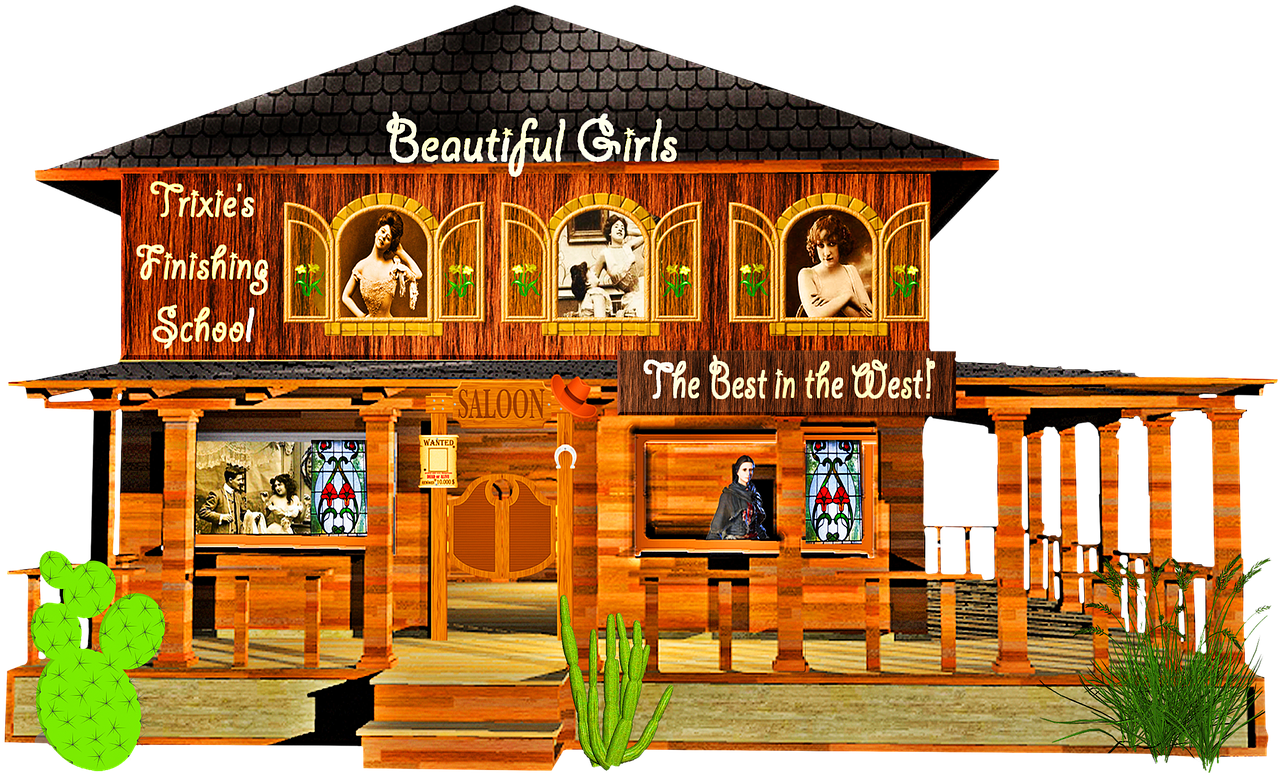

Most people think every woman was working in a high-end parlor house. Not even close. There was a rigid, often brutal social ladder within the world of prostitution in the Wild West, and where you landed on it determined whether you lived in luxury or died in a shack.

At the very top were the madams who ran parlor houses. Think of women like Mattie Silks or Jennie Rogers in Denver. These women were essentially the CEOs of their era. They owned real estate, paid off the police (or the mayor), and lived in opulent surroundings. Their "boarders" were the elite—women who were expected to be well-dressed, literate, and capable of holding a conversation about politics or music. It was expensive. A night in a top-tier Denver parlor house could cost $20 to $50 at a time when a laborer made maybe $1 a day.

Then you had the saloon girls. This is where it gets blurry. Not every woman working in a saloon was a prostitute. Many were "percentage girls" who got a cut of the drinks they talked men into buying. But the line was thin. If the "hurdy-gurdy" house was struggling, the pressure to provide extra services was immense.

The bottom of the barrel? The cribs. These were one-room shacks, barely big enough for a bed and a washbasin. You can still see the remains of these in places like Telluride or Silverton. The women in the cribs—often called "crib girls"—were frequently older, struggling with addiction, or belonging to marginalized ethnic groups, particularly Chinese immigrants who were often trafficked into the country under horrific conditions. Life here was short. Violence was constant. Disease, mostly syphilis and gonorrhea, was a slow-motion death sentence.

Money, Power, and the Economics of the Frontier

Why did they do it? It’s a simple question with a complex answer. Economic agency. In the 1870s, a woman could work as a laundress for pennies, or she could enter the "sporting life" and potentially make more in a night than she’d make in a month of scrubbing shirts.

Historian Anne Butler, who wrote Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery, argues that for many, it wasn't a choice made out of "looseness," but a calculated move in a desperate environment. There were no social safety nets. If your husband died in a mining accident or hopped a train and vanished, you were on your own.

👉 See also: Why Sanctity of Human Life Sunday 2025 Still Matters So Much

Interestingly, these women were often the biggest taxpayers in town. In places like Dodge City or Deadwood, the city treasury relied on the "fines" collected from prostitutes. They weren't usually arrested to stop the trade; they were "arrested" once a month so the city could collect a licensing fee disguised as a legal penalty. It was basically a municipal tax on vice. Without the income from prostitution in the Wild West, many of these towns wouldn't have had the money to build schools or pave roads.

The Myth of the "Heart of Gold"

We love the story of Julia Bulette. She was a famous madam in Virginia City, Nevada. The legend says she was so beloved that when she was murdered, the town held a massive funeral, and the fire brigade marched in her honor. That part is actually true. She was a folk hero who nursed miners during outbreaks of illness.

But the "heart of gold" narrative covers up the darkness. Suicide was incredibly common. Laudanum (opium dissolved in alcohol) was the primary escape. Take the case of "Belgian Lou." She was a well-known figure, but her story ends like so many others—poverty and a lonely death. The violence wasn't just from customers; it was from the lifestyle itself.

Even the famous ones couldn't escape the stigma forever. As soon as "respectable" society—usually the wives of the business owners—arrived in town, the prostitutes were pushed to the outskirts. They went from being the queens of the boomtown to being social pariahs relegated to the Red Light Districts.

Law and Disorder in the Red Light District

The legal status of prostitution in the Wild West was a weird gray area. It was technically illegal in most places, but widely tolerated through "regulated" zones.

Look at El Paso or San Antonio. They had districts like the "Sporting District" or "The Dirty Front." As long as the women stayed within those boundaries and paid their monthly fines, the law looked the other way. It was a symbiotic relationship. The marshals (even famous ones like Wyatt Earp, whose wife Mattie Blaylock was reportedly a prostitute) knew exactly where everyone was. It kept the "vice" away from the "decent" families.

But don't mistake tolerance for safety.

A woman in a crib had zero legal recourse if a man beat her or stole her earnings. The courts rarely took the word of a "sporting woman" over a "citizen." This led to a subculture of protection where madams would hire "bouncers" or the women would carry small "derringer" pistols and "tickler" knives. They had to be their own police force.

The Demographic Reality

It wasn't just white women. The West was a melting pot, and the sex trade reflected that, often in the most tragic ways.

- Chinese Prostitution: In San Francisco and various mining camps, Chinese women were often sold into "contracts" that were effectively slavery. Organizations like the Tongs controlled them. Donaldina Cameron, a social reformer, spent her life trying to rescue these women from the "slave girl" trade in Chinatown.

- Black Women: After the Civil War, many Black women moved West seeking freedom. In the sex trade, they often faced double discrimination, though some, like "Mammy" Pleasant in San Francisco, rose to incredible heights of power and wealth, using her position to fund abolitionist causes and civil rights.

- Mexican and Native American Women: Often pushed to the lowest tiers of the hierarchy due to the prevailing racism of the era, their stories are some of the hardest to recover because they were rarely documented by the newspapers of the time.

Beyond the Saloon: What We Can Learn

So, what’s the takeaway? Prostitution in the Wild West shows us the raw edge of capitalism. It was a place where traditional social structures collapsed, and new, harsher ones took their place.

If you want to understand the real West, stop looking at the gunfights. Look at the ledger books of the parlor houses. Look at the "fine" records in the municipal basements of Kansas and Montana. You’ll find that the "Old West" wasn't built just on gold and cattle, but on the labor of women who were often ignored by history books until very recently.

To get a better handle on this, you should look into the specific records of the "Maverick" women. Start with the archives of the Nevada Historical Society or look up the work of Dr. Jan MacKell Collins, who has done extensive field research on the physical remains of these districts.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs:

- Visit the Site: If you’re in Colorado, go to the Old Homestead House Museum in Cripple Creek. It’s one of the few high-end parlor houses still standing that is preserved as a museum. You can see the actual disparity between the luxury of the madam and the reality of the workers.

- Read Primary Sources: Look for digitized copies of the Police Gazette from the late 1800s. It’s sensationalist, sure, but it gives you a vibe for how the "sporting life" was viewed by the public.

- Check the Census: If you’re a genealogy nerd, look at the 1870 or 1880 census for towns like Leadville, Colorado. Look for large households of women listed as "dressmakers" or "seamstresses" who are all living together. Often, that was the census taker’s polite way of documenting a brothel.

The West was won by many people, but it was financed, in no small part, by the women of the night. Understanding their lives isn't just about "salacious" history; it's about acknowledging the full, complicated human experience of the frontier.