You’re basically a walking, talking construction site that never closes. Right now, as you read this, your cells are frantically assembling microscopic chains of amino acids to keep your heart beating, your skin from sliding off, and your brain capable of processing these words. This chaotic, elegant, and incredibly fast process is what we call protein synthesis. It isn't just a chapter in a high school biology textbook; it’s the literal engine of life. If it stops for even a few seconds, everything falls apart.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle we exist at all. Every single trait you have—the color of your eyes, how well you digest milk, your tendency to get hangry—comes down to how your body handles the synthesis of proteins. It’s the process of taking digital-like code stored in your DNA and turning it into physical, three-dimensional structures.

💡 You might also like: Natural Ways to Relieve Headaches That Actually Help You Feel Better Fast

The DNA Library and the Messy Reality of Transcription

Think of your DNA as a massive, priceless reference book stuck in a library’s "non-circulating" section. That library is your cell's nucleus. The DNA holds all the blueprints, but it’s too bulky and important to leave the room. If the blueprints stayed locked away, nothing would ever get built. This is where the first phase of protein synthesis—transcription—comes in.

Transcription is basically the cell making a "photocopy" of a specific gene. An enzyme called RNA polymerase unzips a section of the DNA double helix. It reads the exposed bases—Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T)—and assembles a complementary strand of messenger RNA (mRNA).

Wait, there’s a catch. RNA doesn't use Thymine. It swaps it for Uracil (U). So, if your DNA says "A," the RNA photocopy says "U." It’s a tiny chemical tweak that lets the cell know this is a temporary message, not the permanent master file.

Once that mRNA strand is ready, it doesn't just head straight to the factory floor. It has to be "edited." In eukaryotic cells (like ours), the mRNA contains "junk" sequences called introns that don't actually code for anything useful. Specialized molecular machinery snips these out and pastes the "good" parts—the exons—back together. It’s like a film editor cutting out the bloopers before the movie hits theaters. Only after this splicing is the mRNA allowed to leave the nucleus and head into the cytoplasm.

Translation: Turning Code into Muscle and Bone

This is where things get weirdly mechanical. If transcription is "writing," then translation is "building." The mRNA strand finds a ribosome, which is essentially a giant protein-making machine made of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins.

The ribosome latches onto the mRNA and starts reading it three letters at a time. These three-letter "words" are called codons. Every codon corresponds to a specific amino acid. For example, the codon AUG is the universal "start" signal. It tells the ribosome, "Hey, start building here."

But how do the amino acids actually get to the ribosome? Enter Transfer RNA (tRNA). These are T-shaped molecules that act like delivery trucks. On one end, they have an "anticodon" that matches the mRNA’s codon. On the other end, they carry a specific amino acid.

- The ribosome reads a codon.

- A tRNA with the matching anticodon docks.

- The ribosome snatches the amino acid from the tRNA and glues it to the growing chain.

- The empty tRNA flies off to go find another amino acid.

It happens fast. Bacterial ribosomes can add about 20 amino acids per second. Human cells are slightly slower but far more precise. This growing chain is called a polypeptide. It’s not a protein yet—not really. It’s just a long, floppy string of beads.

The Folding Problem: Why Shape Is Everything

A protein that isn't folded is useless. Worse than useless, actually—misfolded proteins are the primary suspects behind devastating conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s disease.

The synthesis of proteins doesn't end when the ribosome hits a "stop" codon. Once the polypeptide chain is released, it has to fold into a specific, complex 3D shape. Some parts of the chain are hydrophobic (they hate water) and try to hide in the middle. Other parts are hydrophilic (they love water) and stay on the outside.

Sometimes, the protein needs a "babysitter" to fold correctly. These are called chaperone proteins. They provide a safe, isolated environment for the new protein to wiggle into its proper shape without getting tangled up with other molecules.

Levels of Protein Structure

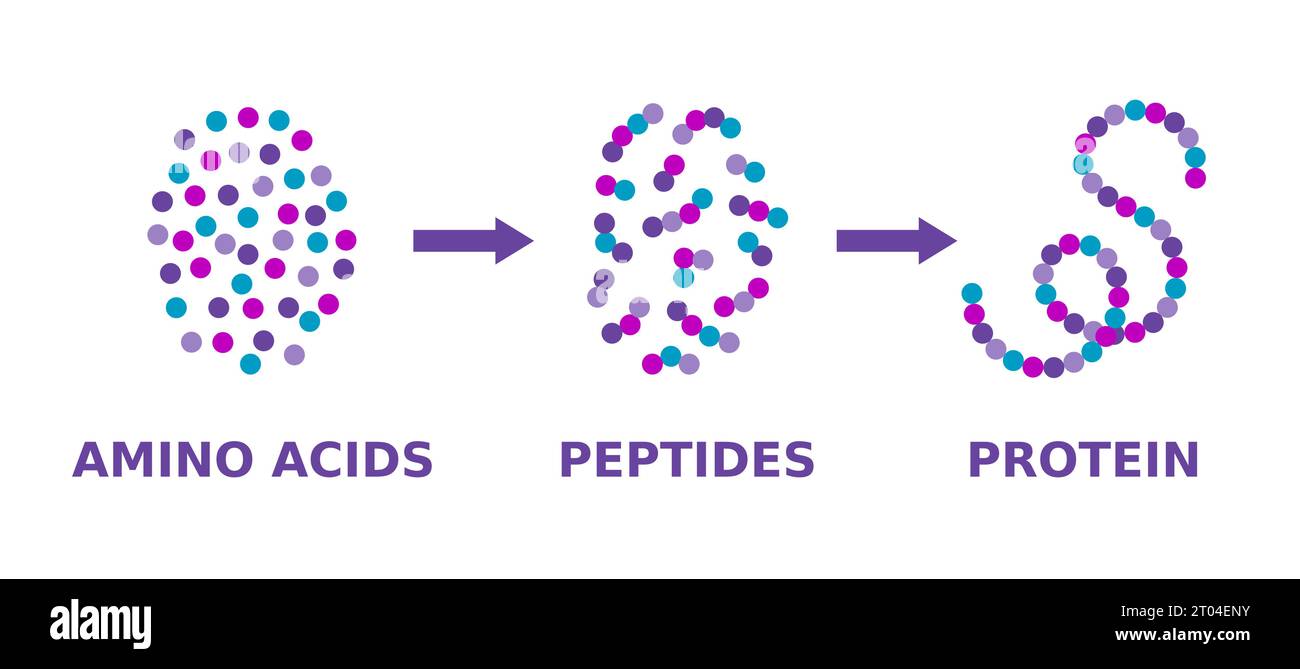

- Primary: The simple sequence of amino acids.

- Secondary: Localized coils (alpha helices) and folds (beta sheets).

- Tertiary: The overall 3D "glob" or fiber.

- Quaternary: When multiple folded chains team up to form a functional unit, like hemoglobin in your blood.

Why Should You Care? (The Real-World Stakes)

If you think this is just abstract science, look at your medicine cabinet. Many of the most powerful drugs we have work by messing with protein synthesis.

Take antibiotics like Tetracycline or Erythromycin. These drugs work by physically gumming up the ribosomes of bacteria. Because bacterial ribosomes are shaped differently than human ones, the drug kills the bacteria by stopping their protein production while leaving yours alone. It literally starves the infection of the tools it needs to survive.

Then there’s the cutting edge of mRNA technology. The COVID-19 vaccines by Pfizer and Moderna essentially "hacked" the synthesis of proteins. Instead of giving you a piece of the virus, they gave your cells the mRNA instructions to build a tiny, harmless piece of the virus (the spike protein). Your own ribosomes built the protein, your immune system saw it, freaked out, and learned how to fight it. It turned your body into its own vaccine manufacturer.

Common Misconceptions About Protein Production

Most people think that if they eat more protein, they’ll automatically build more muscle. Kinda true, but mostly not.

🔗 Read more: Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women's Hospital: What to Actually Expect During Your Stay

Your body doesn't just take the protein from a steak and shove it into your biceps. It breaks that steak down into individual amino acids. These go into a "pool" in your blood and tissues. The synthesis of proteins is governed by your DNA and hormonal signals (like mTOR), not just by how much chicken you eat. If you don't provide a stimulus—like lifting heavy weights—your body isn't going to initiate the synthesis of new muscle tissue just because the raw materials are sitting around. It’ll just burn the extra amino acids for energy or pee them out.

Another big one: "DNA is the blueprint for everything."

Technically, DNA is the blueprint for proteins. But proteins do everything else. They make the enzymes that build fats and carbohydrates. They form the receptors that let you feel dopamine. They are the "boots on the ground." DNA is just the instruction manual; the synthesis of proteins is the actual construction work.

Nuance: The Cost of Mistakes

Your cells are incredibly good at "proofreading," but they aren't perfect. Mutations in the DNA can lead to the wrong amino acid being placed in the chain. In Sickle Cell Anemia, a single "typo" in the DNA (one A changed to a T) causes one specific amino acid (Glutamic Acid) to be replaced by another (Valine).

That tiny swap changes the way hemoglobin folds. The protein clumps together, deforming the red blood cells into sickle shapes that get stuck in capillaries. One single error in the synthesis of proteins can change an entire life.

How to Support Your Body's Protein Factory

You can't "force" your cells to synthesize proteins better, but you can definitely get out of their way.

First, stop skimping on sleep. A huge portion of protein synthesis, especially for tissue repair and growth hormone regulation, happens while you’re knocked out. Chronic sleep deprivation is like trying to run a factory during a power flickering—lots of errors and very little output.

Second, watch your micronutrients. You need more than just amino acids. Zinc, for instance, is a crucial cofactor for the enzymes involved in DNA transcription. Magnesium is required for the ribosome to stay stable while it's reading mRNA. If you're deficient in these, the synthesis of proteins slows to a crawl regardless of how much protein powder you're chugging.

📖 Related: What Kills Strep Throat: Why Antibiotics Still Reign and What Actually Works for the Pain

Actionable Next Steps

- Prioritize Complete Proteins: Ensure you're getting all nine essential amino acids—the ones your body can't make on its own. If you’re plant-based, mix your sources (like beans and rice) to cover the full spectrum.

- Timing Matters (A Little): While the "anabolic window" is often exaggerated, consuming protein after a workout provides the necessary "building blocks" exactly when your body’s synthesis signals are peaked.

- Manage Stress: High levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) are catabolic. This means they actually signal your body to break down proteins rather than build them.

- Stay Hydrated: Translation happens in the aqueous environment of the cytoplasm. Dehydration can physically hamper the movement of tRNA and ribosomes.

The synthesis of proteins is the most fundamental process in your biology. It’s the bridge between the digital information of your ancestors and the physical reality of your body today. Understanding it isn't just for scientists; it’s about understanding the very mechanics of how you stay alive.