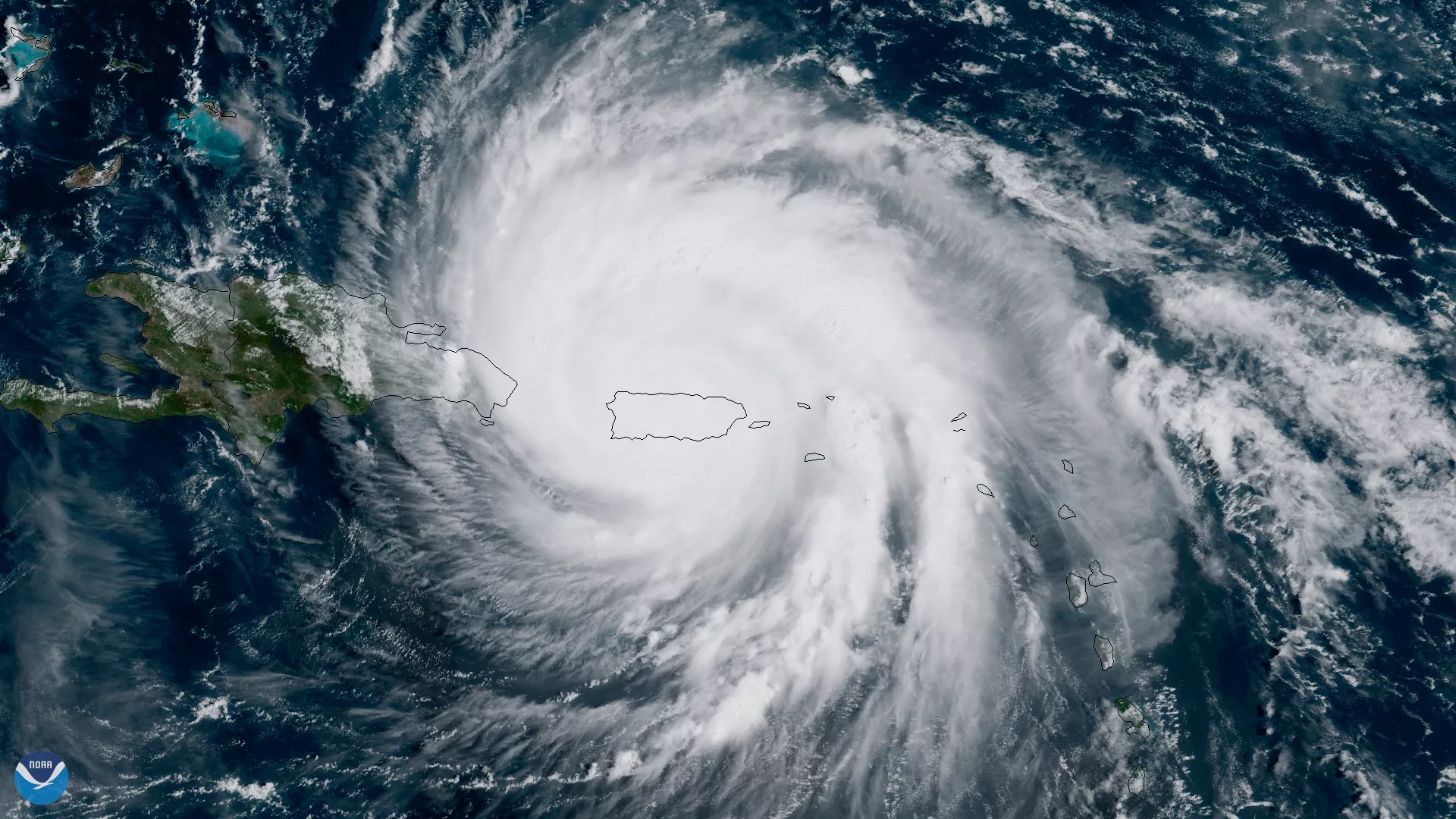

If you want to understand the soul of an island, don’t look at it when the sun is out and the piña coladas are flowing. Look at it when the lights go out. For 3.2 million people, the lights didn't just flicker on September 20, 2017. They stayed off. In some places, for nearly a year.

Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria has become a case study in grit, but also in the systemic exhaustion that comes with being a "territory." You’ve seen the photos of the blue tarps. You probably heard about the official death toll jump from 64 to nearly 3,000 after the George Washington University study forced a reality check. But that was years ago. Since then, the island has endured a literal "summer of '19" protest that ousted a governor, a series of punishing earthquakes in the south, and a global pandemic.

People think things are "back to normal." They aren't. Not exactly. Normal is a moving target when you’re dealing with a power grid held together by zip ties and hope.

The Grid: LUMA and the Never-Ending Blackout

You can't talk about Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria without talking about the electricity. Or the lack of it. In 2021, a private company called LUMA Energy took over the transmission and distribution from the state-owned PREPA. The idea was simple: privatization would bring efficiency.

The reality? It’s complicated.

Ask anyone in San Juan or the mountain towns of Utuado. Voltage fluctuations still fry refrigerators. Blackouts happen on sunny Tuesdays for no apparent reason. In April 2022, the whole island went dark because of a fire at the Costa Sur power plant. Just like that. Back to square one.

But here is the twist: Puerto Ricans stopped waiting for the government. There is a massive, grassroots solar revolution happening. According to the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC), there are now over 110,000 rooftop solar installations on the island. Compare that to basically zero before Maria. Families are taking out loans they can barely afford just to ensure their insulin stays cold and their kids can do homework. It’s decentralized resilience. It’s beautiful, and it’s a tragedy that it’s necessary.

The Act 60 Debate: Paradise for Whom?

The economy of Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria has felt like two different worlds colliding. On one hand, you have the locals. The cost of living is skyrocketing. Eggs are expensive. Rent in areas like Santurce or Rincón has doubled or tripled.

On the other hand, you have the "tax grifters"—or "investors," depending on who you ask.

Act 60 (formerly Act 20 and 22) offers massive tax breaks to wealthy individuals who move to the island. They pay 0% on capital gains. Local business owners? They pay the standard corporate rates. This has created a weird, simmering tension. You see "Gringo Go Home" graffiti next to a brand-new $15 avocado toast cafe.

The narrative often ignores the middle ground. Some of these newcomers are genuinely trying to integrate and build. But many are just there for the 4% corporate tax rate, driving up real estate prices until the people who survived Maria can no longer afford to live in the neighborhoods they helped rebuild.

Agriculture and the 85% Problem

Before Maria, Puerto Rico imported about 85% of its food. When the ports closed, the grocery store shelves didn't just get thin—they went bare. It was a wake-up call that tasted like hunger.

🔗 Read more: The US Army Mountain Warfare School: Why This Vermont Secret is the Military's Toughest Classroom

Since then, there’s been a visible shift toward agroecología. Small farms like Departamento de la Comida have been pushing for food sovereignty. It’s hard work. The soil was stripped by the winds. But you see it in the farmer's markets in Old San Juan. People are growing kale, passion fruit, and root vegetables like yautía with a newfound urgency. They realize that in the next "big one," the Jones Act—that century-old law requiring goods to be shipped on US-built and operated vessels—might again make relief efforts a logistical nightmare.

The Trauma No One Mentions

We talk about infrastructure. We talk about FEMA. We rarely talk about the collective PTSD.

Puerto Rico since Hurricane Maria is an island that flinches when the wind picks up. Every June, when hurricane season starts, there is a palpable shift in the air. People stock up on canned tuna and batteries. Not because they are prepared, but because they remember.

The 2020 earthquakes in the south—Guánica, Yauco, Ponce—didn't help. They happened in the middle of the night. People slept in their cars for weeks because they were afraid their roofs would collapse. It was a compounding trauma. It’s why you see so many young people leaving for Orlando or Philadelphia. It isn't just about the money; it’s about the mental load of wondering when the next "historic" event will reset your life to zero.

Politics and the "Summer of '19"

If you think Puerto Ricans are passive, you weren't watching in July 2019. After a leaked Telegram chat showed Governor Ricardo Rosselló and his inner circle mocking Maria victims and making homophobic slurs, the island exploded.

Over a million people—a third of the population—marched down the PR-18 highway. They banged pots and pans (the cacerolazo). They danced. They demanded he resign. And he did.

This changed the political DNA of the island. The two-party system (PNP and PPD) that has dominated for decades is cracking. New parties like Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana (MVC) and Proyecto Dignidad are gaining ground. People are realizing that the status quo—this "limbo" between statehood and independence—is exactly what made the Maria recovery so slow.

Realities of the Reconstruction

Where is the money? That’s the $80 billion question.

FEMA has obligated billions, but the "spend-down" is notoriously slow. You’ll still see schools with mold and bridges that are "temporary" fixes five years later. Part of this is the Oversight Board (La Junta), appointed by the US government to manage Puerto Rico's debt. They want austerity. The people want a functioning hospital in Vieques—the small island offshore that still doesn't have a proper birthing center or emergency room years after Maria destroyed the old one.

Practical Insights for Moving Forward

If you are looking at Puerto Rico today—whether as a traveler, an investor, or someone with family there—you have to see it clearly. It is not a victim. It is a survivor with a very long "to-do" list.

- Support Local Directly. If you visit, skip the chains. Eat at the chinchorros. Stay at locally owned guest houses. The "trickle-down" from big resorts rarely reaches the mountain communities that need it most.

- The Solar Future is Now. If you live there or are moving there, the grid is not your friend. Investing in a Tesla Powerwall or a Sunrun system isn't a luxury; it’s a basic utility requirement for peace of mind.

- Understand the Jones Act. To understand why everything is expensive, read up on the Merchant Marine Act of 1920. Supporting its waiver for Puerto Rico is one of the single most impactful "pro-economy" stances anyone can take.

- Follow Local Journalism. Sources like Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI) are the ones who actually uncovered the death toll and the Rosselló chats. They are the watchdogs in a system that often lacks accountability.

Puerto Rico is currently in a state of "reconstruction fatigue." The initial surge of volunteer energy has faded, leaving the locals to navigate the bureaucracy of recovery alone. Yet, the cultural output—the music, the art, the community kitchens—has never been more vibrant. It is a place that has learned that "the government isn't coming," and has decided to build its own future anyway.

Next Steps for Action

To get a true sense of the progress on the ground, monitor the FEMA Puerto Rico Recovery data portal for actual project completion rates versus "obligated" funds. If you want to contribute to the island's energy independence, look into organizations like Casa Pueblo in Adjuntas, which has successfully transitioned an entire mountain town to solar power. For those tracking the economic shifts, the Center for a New Economy (CNE) provides the most objective analysis of how federal aid and tax policies are actually impacting the local poverty rate.