Ever noticed how often you’re asked to pick a random number from 1 to 15? It happens during icebreakers at work. It pops up in elementary math worksheets. Heck, it’s even the basis for how some board games determine who goes first when a standard die just won't cut it.

People think "random" means anything goes. It doesn't.

When you ask a human to pick a number between 1 and 15, they almost never pick 1. They rarely pick 15. They gravitate toward the middle, usually landing on 7 or 13, because our brains are weirdly predictable even when we're trying to be chaotic.

The Math Behind a Random Number From 1 to 15

To understand why this range is a staple in probability, we have to look at the discrete uniform distribution. In a truly random system—like a computer algorithm—every single integer has exactly a 6.67% chance of being selected.

Computers don't actually do "random" well. They use what’s called a Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG). Most modern systems, like those used in Python’s random module or JavaScript’s Math.random(), rely on the Mersenne Twister algorithm. It takes a "seed" value—often the current timestamp down to the millisecond—and runs it through a complex mathematical grinder to spit out a value.

If you’re coding a simple picker, the formula usually looks something like this:

$$\text{floor}(\text{random}() \times 15) + 1$$

But for humans? Logic goes out the window. We have "lucky" numbers. We have "bad" numbers.

Why the Number 7 Wins Every Time

Ask a hundred people for a random number from 1 to 15 and I bet my morning coffee that 7 shows up more than its fair share. Why? Cognitive scientists call it the "Blue-Seven Phenomenon."

Back in the 1970s, researchers like Simon and Wiltz found that when people are asked to name a number and a color, a statistically staggering amount of people say "Blue" and "7." In the 1-15 range, 7 feels "central" but not "too central" like 8. It feels "prime." It feels intentional.

How to Get a Truly Random Result

If you actually need a fair result for a giveaway or a classroom assignment, don't trust your brain. Your brain is biased. It’s cluttered with birthdays and sports jerseys.

- Physical Tools: Use a 16-sided die (d16) and reroll the 16. These are common in tabletop gaming circles like Dungeons & Dragons.

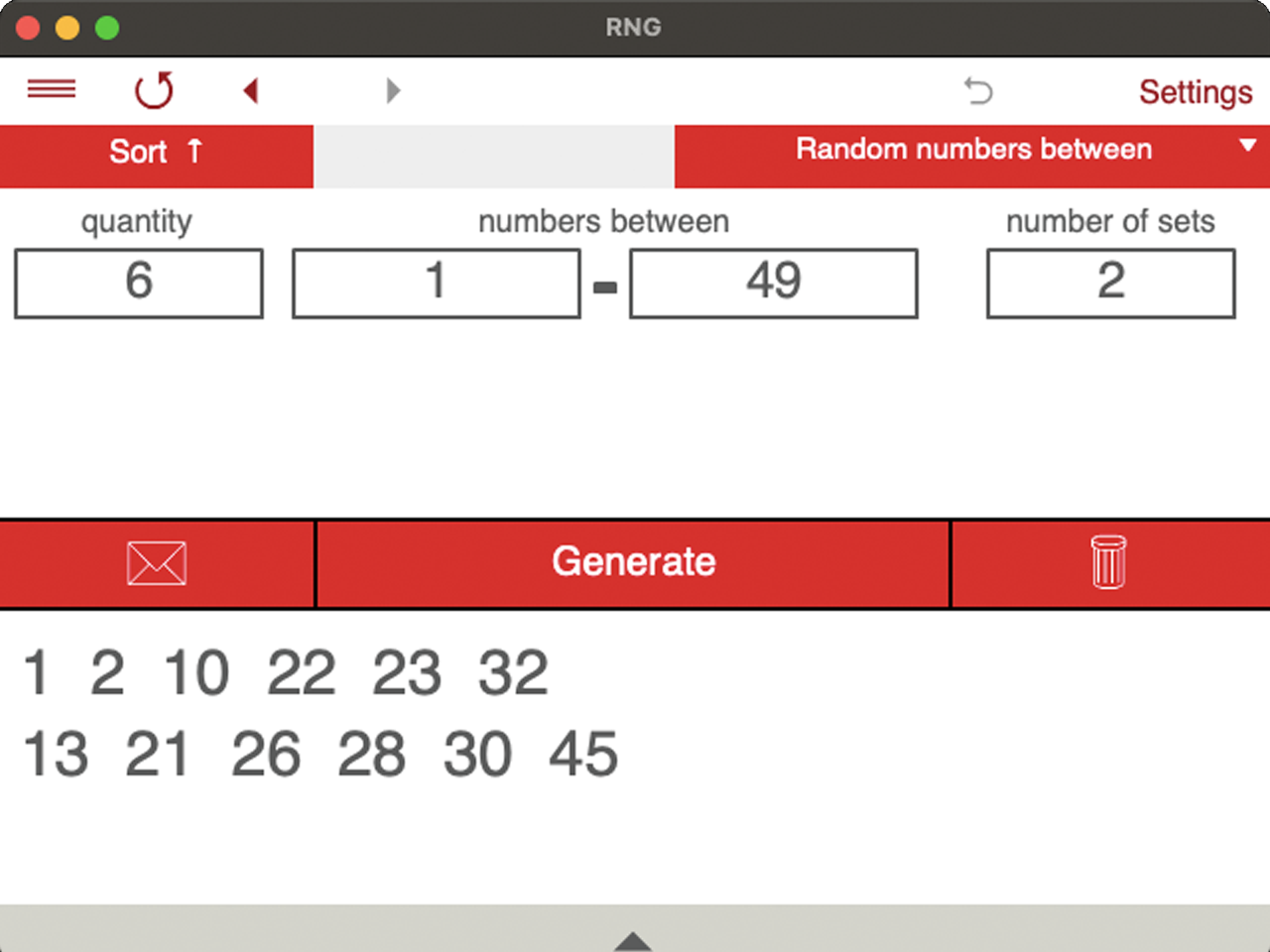

- Digital RNGs: Google has a built-in tool. Just search "random number generator" and set the parameters.

- Atmospheric Noise: Sites like Random.org use atmospheric noise (radio frequency interference) to generate numbers. This is "true" randomness because it’s not based on a predictable computer seed.

Honestly, most of us just need a quick way to settle a bet. If you’re using a phone, the "Siri" or "Google Assistant" voice commands are surprisingly robust for this. They don't have the "middle-number bias" that humans do.

The Psychological Weight of the 1 to 15 Range

This specific range is a "sweet spot" in psychology. It’s larger than a 1-10 scale, which feels too restrictive and prone to "top of mind" bias. It’s smaller than 1-100, which causes "choice paralysis."

In 1956, George Miller published a famous paper called The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. He argued that the human short-term memory can only hold about 7 bits of information. By expanding a range to 15, you’re essentially doubling that capacity. It forces the brain to move from "instant recognition" to "deliberate selection."

📖 Related: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessed With the Jellycat Bashful Bunny Large

Common Use Cases You Might Not Think About

- Raffles: Small office pools often cap at 15 to keep the odds high enough to be exciting but low enough to guarantee a winner quickly.

- Music Theory: While an octave has 8 notes, two octaves (minus the repeat) take us into the 15-note territory.

- Sports: Think about the 15-minute quarters in the NFL. It’s a foundational block of time.

When Randomness Fails

Sometimes, "random" isn't what we actually want.

Spotify learned this years ago. When their "Shuffle" feature was truly random, people complained. They’d hear three songs by the same artist in a row. Users thought the shuffle was broken. Spotify had to change the algorithm to be less random and more "distributed" to feel more random to humans.

The same applies when you’re picking a random number from 1 to 15 for a group. If you pick 4 three times in a row, people will think you’re cheating. Mathematically, that's totally possible. Psychologically, it’s a disaster.

Actionable Tips for Fair Selection

If you are the one in charge of picking a number for a group or a project, follow these steps to ensure nobody feels cheated:

- Declare the method first. Tell the group, "I'm using a Google RNG," before you click the button.

- Avoid "think of a number." If you are the leader, never pick the number yourself. You are subconsciously biased toward your birth month or the current hour.

- Use the "Second Hand" trick. If you don't have a computer, look at an analog watch. Look at where the second hand is. If it’s between 0-4 seconds, that’s 1. 5-8 seconds, that’s 2. This is a crude but effective way to use external entropy.

To get the best results, stick to hardware-based generators for anything involving money or high stakes. For everything else, just remember that 7 is a trap. Pick 13. Or 2. Nobody ever expects 2.