You’ve probably seen them on the local news—those jagged blue lines sweeping across the Midwest or diving down from Canada like a literal blade. They look simple. It’s just cold air, right? Well, sort of, but mostly no. If you’re staring at a us cold front map trying to figure out if you need to cancel your weekend hike or wrap your pipes, there is a lot more happening between those blue triangles than just a drop in temperature.

Weather is messy.

Most people think a cold front is a giant wall of ice. In reality, it’s a transition zone. It is the leading edge of a cooler, denser air mass that’s aggressively shoving its way under a warmer, moister air mass. Because that cold air is heavier, it acts like a snowplow. It lifts the warm air up fast. That rapid lift is exactly why cold fronts are the main culprits behind those "where did that come from?" thunderstorms that tear through the Plains and the Southeast.

What those blue lines actually mean

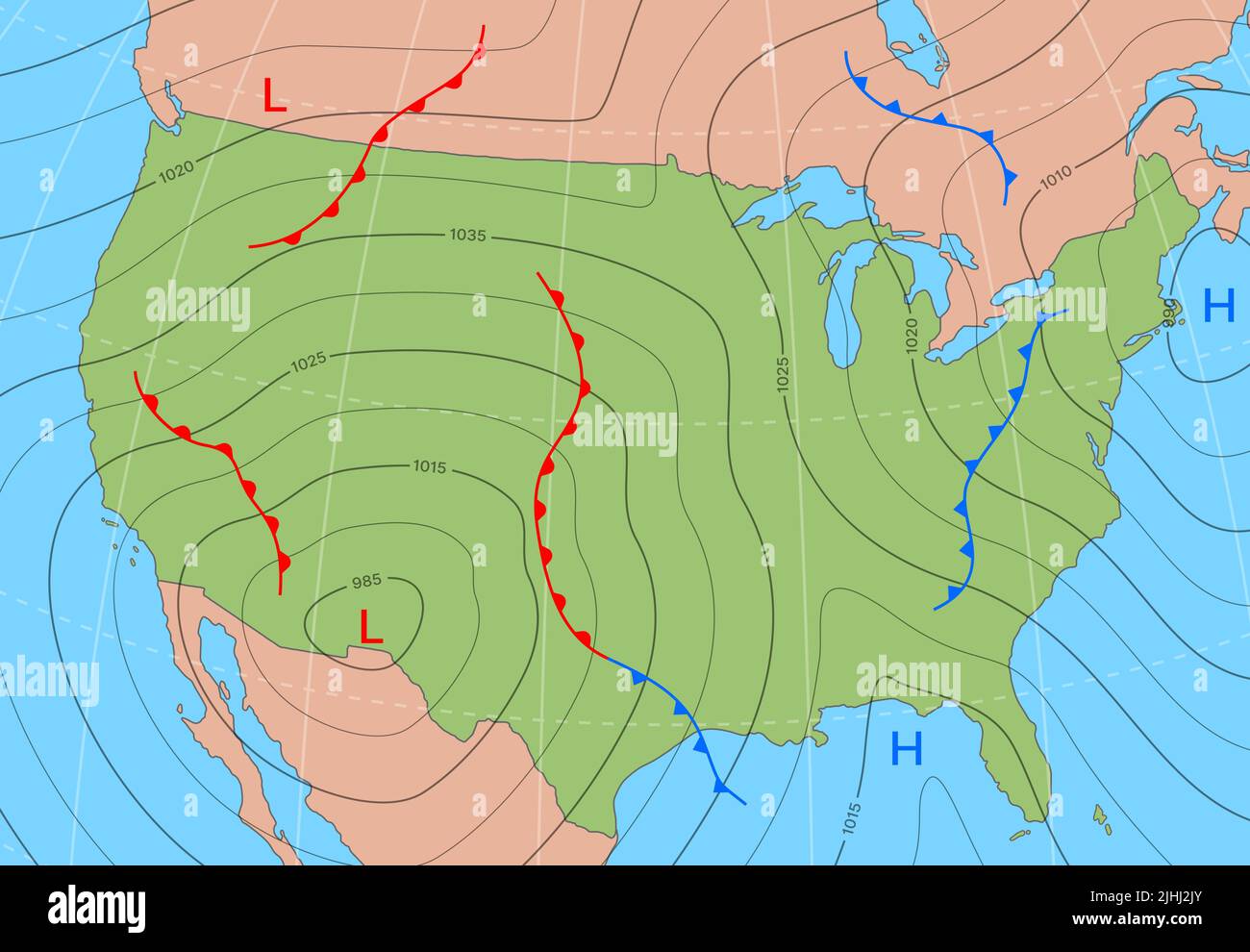

When you look at a professional us cold front map from the National Weather Service (NWS) or NOAA, you’ll notice those blue triangles always point in the direction the air is moving. If the triangles are pointing at Tennessee, Tennessee is about to get hit. It's a literal directional arrow.

But here is the thing: the map doesn't show you the "behind the scenes" physics.

As that cold air pushes in, the atmospheric pressure usually starts dropping. You might feel it in your joints or your head before you even see a cloud. Then, right as the front passes, the pressure bottoming out is followed by a sharp rise. The wind shifts too. Usually, it goes from a southerly flow to a crisp, biting north or northwest wind. If you see the triangles on the map crossing your city, expect the wind to do a 180-degree turn within an hour or two.

Why the maps look different in the West versus the East

The geography of the United States makes our weather maps look like a chaotic art project. In the West, cold fronts hit the Rockies and get all chewed up. The mountains break the physical continuity of the front, which is why a us cold front map might show a broken or "discontinuous" line over Colorado or Utah.

Once that air spills over the mountains and hits the flat Great Plains? That’s when things get real.

✨ Don't miss: Rancho Bernardo Fire Today: What You Need to Know Right Now

Out there, there’s nothing to stop the momentum. This is where you see those long, clean lines stretching from Texas all the way up to the Great Lakes. Meteorologists at the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) watch these specific setups for "linear" storm development. When the front is straight and fast-moving, it often triggers a squall line—a long row of high-wind thunderstorms that can travel hundreds of miles without stopping.

The moisture factor you can't see on the lines

A cold front is only as dangerous as the air it’s replacing.

If a front is moving into dry, desert air in Arizona, you might just get a few clouds and a bit of dust. It's a "dry front." But if that same front hits the Gulf of Mexico moisture hanging over Mississippi? That's when you get the sirens. The moisture acts as fuel. The cold front is the spark.

If you are tracking a us cold front map during the spring or fall—what we call the "transition seasons"—you need to look at the dew point ahead of the line. If the dew points are in the 60s or 70s, that blue line is a fuse.

It's not always about a "freeze"

People get tripped up by the name. A "cold" front doesn't always mean it's going to be snowing. In the middle of a July heatwave in Georgia, a cold front might just mean the temperature drops from 98 degrees to a much more manageable 85 degrees. It’s "cold" relative to what was there before.

👉 See also: Tonight's Debate Explained: What Really Happened to the Schedule

The real indicator of a powerful front on a us cold front map is the contrast. Meteorologists look at the "gradient." If it's 80 degrees in front of the line and 45 degrees behind it, that's a massive energy imbalance. That’s where you get the 60 mph wind gusts. Nature hates an imbalance and tries to fix it as violently as possible.

Reading the "Frontal Slope"

Imagine the front as a physical wedge. Cold fronts have a very steep slope compared to warm fronts. A warm front is like a gentle ramp; it slides over the top of cold air slowly, creating days of gray, drizzly weather.

Cold fronts are the opposite. They are steep and aggressive.

This is why cold front weather is usually intense but short-lived. You get the "big show"—heavy rain, thunder, maybe some hail—and then it clears out. The air behind a cold front is typically much drier. Once that blue line passes you on the map, look for the "clearing line" in the sky. You’ll see the back of the clouds moving away, leaving behind a deep, vivid blue sky that looks almost polished.

How to use this data for real-world planning

If you’re looking at a us cold front map today, don't just look at where the line is now. Look at the timing. Most fronts move at about 20 to 30 miles per hour, though "blue northers" in Texas can move much faster.

- Check the wind barbs: If the map has little sticks with lines on them (wind barbs), see if they are perpendicular to the front. The more perpendicular they are, the faster the front is moving.

- Watch the tail: Cold fronts often have a "tail" that drags. The northern part of the front might sweep through quickly while the southern end stalls out. If that line stops moving, it becomes a "stationary front." That is bad news. Stationary fronts are responsible for major flooding because the rain just sits over the same spot for 24 hours.

- Look for the pressure trough: Sometimes a "pre-frontal trough" develops ahead of the actual cold front. On a us cold front map, this might look like a dashed line. This is basically a "scout" for the main front, and it can trigger its own round of nasty weather before the temperature even drops.

The "Backdoor" Cold Front

There is a weird phenomenon mostly seen in New England and the Mid-Atlantic called a "backdoor" cold front. Usually, weather moves West to East. But occasionally, a high-pressure system over the Canadian Maritimes pushes cold, damp Atlantic air toward the Southwest.

On a us cold front map, you'll see the blue line moving the "wrong" way—from the Northeast down toward D.C. or Virginia. These are notorious for catching people off guard because the local forecast might call for a sunny day, but then this chilly, foggy "backdoor" front slides in and drops the temp by 20 degrees in the middle of the afternoon.

Accuracy and limitations of digital maps

We have better data than ever, but micro-climates still mess with the maps. A standard us cold front map you see on a phone app is often a simplified version of reality. It might not account for how the Great Lakes are warming the air or how the Appalachian Mountains are pinning the cold air against the coast (a process called cold air damming).

Always cross-reference the visual map with the "Forecast Discussion" from your local NWS office. Those are written by actual humans who know the quirks of your local terrain. They’ll tell you if that blue line on the map is actually going to deliver a punch or if it’s going to "fizzle out" before it reaches your zip code.

✨ Don't miss: When Did America Begin? The Dates Most People Get Totally Wrong

Next Steps for Tracking Weather Events

To get the most out of a us cold front map, start by identifying the "parent" Low Pressure system. These fronts don't just exist in a vacuum; they are usually attached to a center of low pressure (a red 'L' on the map). If the 'L' is deep and the isobar lines (the thin gray circles) are packed tightly together, the front will be extremely windy.

Check the surface analysis charts updated every three hours by the Weather Prediction Center. This gives you a near real-time look at how the front is evolving. If you see the blue line start to merge with a purple line (an occluded front), it means the system is reaching its peak and will likely start weakening soon.

Pay attention to the temperature "spread" across the front. If the gap between the warm air and cold air is widening, the front is gaining strength. This is the most reliable way to predict if you're looking at a minor jacket-weather day or a legitimate atmospheric event.