Robert Wood Johnson wasn't just a guy who started a company. He was a radical. If you walked into a hospital in 1870, you were basically walking into a death trap. Doctors wore their blood-stained frock coats like badges of honor, and they didn't wash their hands between patients. It’s gross. Honestly, it’s terrifying to think about. But Robert Wood Johnson, the primary Johnson & Johnson founder, saw something most people ignored: the invisible world of germs.

He listened to Joseph Lister. While the rest of the medical establishment was laughing at Lister’s "germ theory," Johnson was obsessed. He realized that if you could mass-produce sterile surgical dressings, you wouldn't just be selling bandages. You’d be saving lives on a scale no one had ever seen.

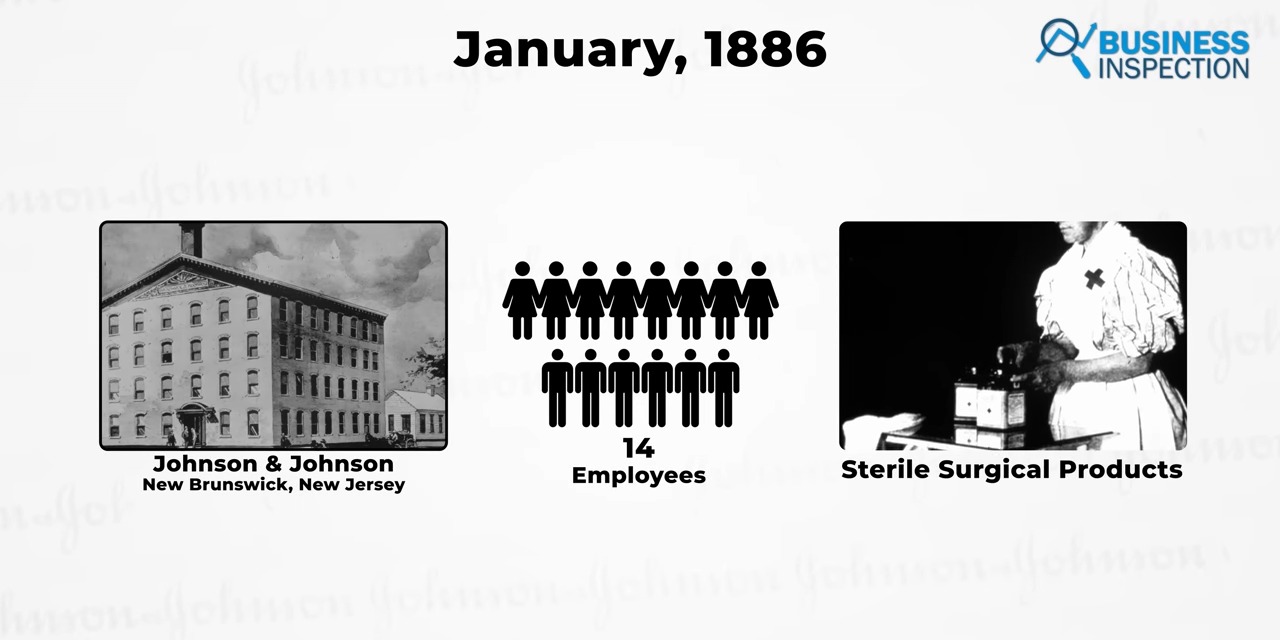

Most people think of the brand and think of baby powder or Band-Aids. But the real story is about three brothers—Robert, James, and Edward—and a small wallpaper factory in New Brunswick, New Jersey. They had fourteen employees. That’s it. From that tiny, dusty start in 1886, they pivoted from making medicated plasters to creating the entire infrastructure of modern healthcare. It wasn't a straight line to success. It was a messy, risky bet on science that most people thought was total nonsense at the time.

The Robert Wood Johnson Gamble: Why Sterile Surgeries Changed Everything

Before the Johnson & Johnson founder got involved, surgery was a last resort. If the surgery didn't kill you, the infection almost certainly would. Surgeons would use "charpie"—which was basically old rags swept off the floor of textile mills—to pack wounds. Imagine that. You’re already cut open, and they’re stuffing you with floor scraps.

Robert Wood Johnson changed the game by creating the first-ever mass-produced sterile surgical dressings. He didn't just invent a product; he had to invent the machines to make the product. He had to build a culture of cleanliness that didn't exist yet. By 1887, the company published Modern Methods of Antiseptic Wound Treatment. This wasn't just a catalog. It was a textbook. They distributed it for free to thousands of doctors.

This is where the business genius kicks in. By teaching doctors how to perform safer surgeries, Johnson created a massive market for his own products. It was education-based marketing before that was even a buzzword. He knew that if he could prove Listerism worked, his company would become the backbone of every hospital in America. He was right. By the time the Spanish-American War rolled around, the U.S. Army was relying on J&J's compressed surgical kits.

The Weird History of the First Aid Kit

Did you know the first aid kit actually started because of a conversation on a train? It’s true. Robert Wood Johnson was talking to a railway surgeon. Back then, working on the railroad was incredibly dangerous. If a worker got hurt out in the middle of nowhere, there was zero medical help. The surgeon told Johnson they needed something portable to stabilize workers until they could get to a hospital.

In 1888, the first "Railway Station and Factory Supply Case" was born. It was a heavy wooden box packed with gauze, bandages, and sutures. It’s kind of wild to think that every orange plastic box in a school gym or every kit in the back of an Uber today traces back to that one train ride.

🔗 Read more: Why Managing a Cooling and Winter Law Office is Harder Than You Think

It Wasn't Just One Johnson & Johnson Founder

While Robert was the visionary and the powerhouse, he couldn't have done it without James Wood Johnson and Edward Mead Johnson. James was the engineer. He was the one who actually designed the machinery in that old wallpaper mill to produce the cotton and gauze. He was meticulous.

Edward was different. He was more of a salesman, but he eventually left the company because he wanted to focus on nutritional products. He went on to found Mead Johnson & Company—the people who make Enfamil. So, if you’ve ever fed a baby formula, you’re still technically touching the legacy of the original J&J family tree.

Why the Red Cross Logo Caused a Century of Drama

You’ve seen the red Greek cross on their packaging. The Johnson & Johnson founder started using that symbol in 1887. But here’s the kicker: The American Red Cross was founded around the same time by Clara Barton.

For over a hundred years, there was this weird, low-key tension (and eventually high-key lawsuits) over who actually owned the right to use the red cross. J&J actually had the trademark first in the U.S. It wasn't until 2008 that they finally settled the legal battles. It’s one of those bizarre corporate footnotes that shows just how protective Robert Wood Johnson was of his brand's visual identity from day one.

The Transition to General Robert Wood Johnson

Robert Wood Johnson I died in 1910. His son, Robert Wood Johnson II—often called "The General"—took over eventually and turned the company into a global monster. He was the one who wrote "Our Credo."

If you go to J&J headquarters today, the Credo is literally carved into the stone. It says the company’s first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses, and patients. Stockholders come last. In the 1940s, this was radical. Most CEOs would have been fired for saying the shareholders weren't the top priority. But The General believed that if you took care of the customers and the employees, the profit would just... happen.

This philosophy was put to the ultimate test during the Tylenol crisis in 1982. Even though the founder was long gone, his ethos was baked into the walls. When those bottles were tampered with in Chicago, the company didn't wait for a government order. They pulled 31 million bottles off the shelves immediately. It cost them $100 million. But it saved the brand. That’s the direct result of the culture Robert Wood Johnson started in 1886.

Lessons from the Johnson & Johnson Founder for Today's Business

So, what can we actually learn from a guy who’s been dead for over a century? It’s not about bandages.

- Solve a problem people don't know they have yet. People in 1880 didn't know they needed "sterile" gauze. They just knew they were dying of "hospital fever." Johnson identified the cause and sold the solution.

- Education is the best sales tool. Don't just sell a widget. Teach your customers how to be better at their jobs using your widget.

- Trust is a long-term asset. Robert Wood Johnson knew that in healthcare, if people don't trust your name, you're done.

The company has changed a lot. They’ve faced massive lawsuits over talc and opioids recently. It’s complicated. Critics argue that the modern corporation has drifted far from the original vision of the Johnson & Johnson founder. Whether that’s true or not, you can't deny that the basic standards of hygiene in every doctor's office you visit today started with Robert Wood Johnson’s obsession with invisible microbes.

Actionable Insights for Entrepreneurs and Leaders

If you’re looking to apply the "Johnson Method" to your own work, start here:

- Audit your "Credo." Write down who you are actually responsible to, in order. If "profit" is number one, you might win short-term but lose the decade.

- Look for "Dirty" Industries. Robert Wood Johnson looked at the "dirty" state of surgery and saw an opportunity for "clean." Where is there currently a lack of standards or a "messy" process in your field?

- Invest in Scalable Infrastructure. The brothers didn't just make bandages by hand; they built a factory that could supply the world. Think about how your service can be systematized so it doesn't rely on your personal labor.

- Study the History of Your Field. Robert Wood Johnson was a student of Joseph Lister. He didn't invent germ theory; he commercialized it. Find the "academic" or "fringe" idea in your industry that is actually true and figure out how to bring it to the masses.

The legacy of Robert Wood Johnson is a reminder that the biggest companies usually start with a very simple, very human goal. For him, it was just making sure a routine surgery didn't turn into a death sentence.