In 1999, everyone expected a robot version of Mrs. Doubtfire. Instead, they got a 200-year-long existential crisis about mortality and legal personhood. Robin Williams Bicentennial Man didn't just fail at the box office; it confused the heck out of people who wanted the manic, "shazbot" energy of Mork.

Looking back from 2026, the film hits different.

We’re living in an era where AI is basically our roommate. Back then? It was just a weird high-concept drama with a $100 million price tag. Disney and Sony split the bill because the budget was so terrifyingly high for a "philosophical" film.

The $100 Million Gamble on a Metal Suit

Hollywood was convinced that Robin Williams plus a family-friendly director like Chris Columbus meant instant gold. They were wrong. The movie grossed about $87 million worldwide. That’s a disaster when you realize it needed nearly double its budget just to break even after marketing.

People blamed the suit.

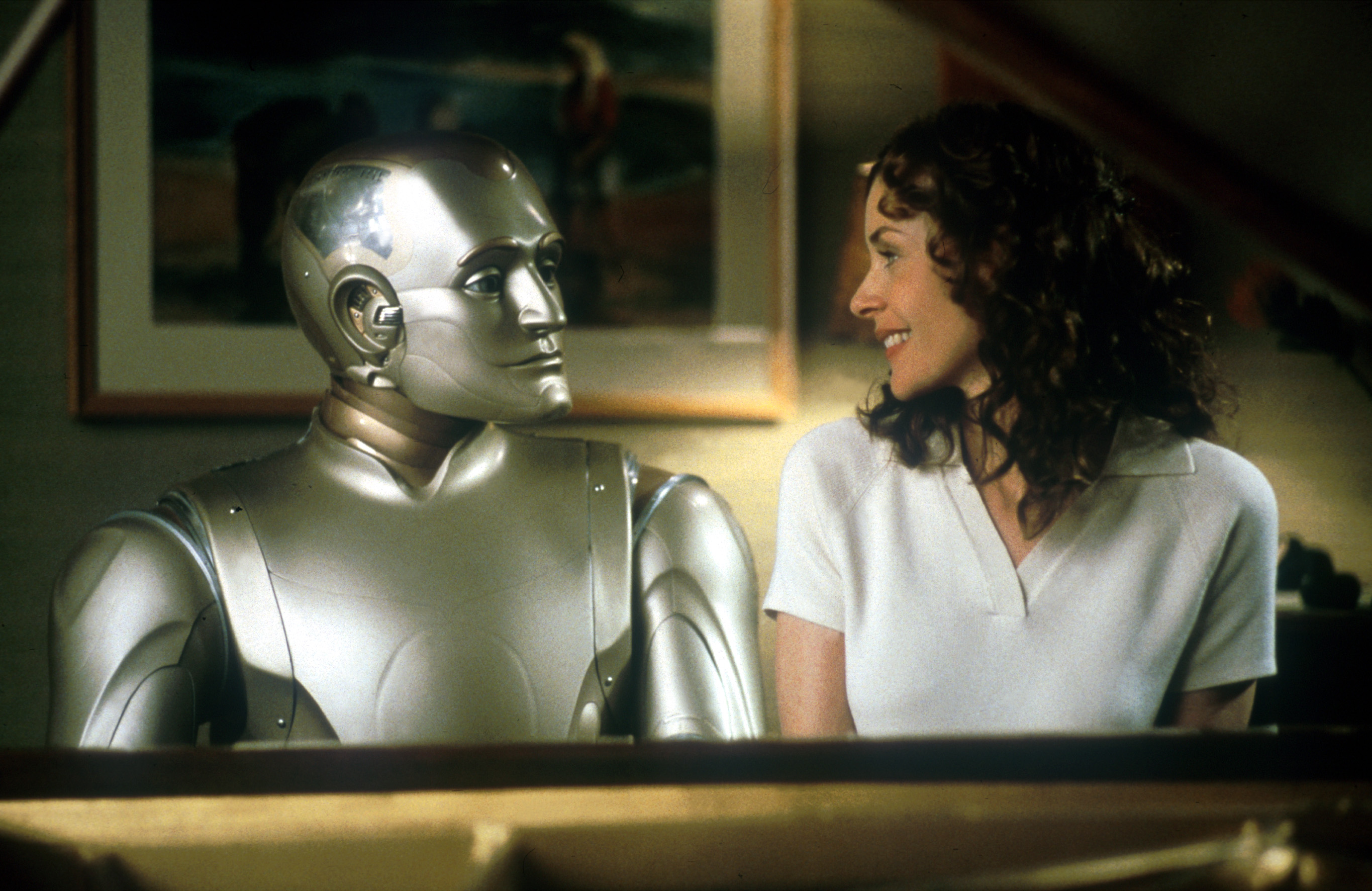

Honestly, it’s wild how much effort went into that thing. It wasn't CGI. For most of the first half, Robin was actually inside a 30-pound suit of armor designed by Steve Johnson’s XFX team. There were two versions: a "hero" suit that was flexible enough for Robin to move in, and a rigid one for a stunt double.

Imagine one of the world's most hyperactive comedians trapped in a metal shell.

He had to convey everything through posture and a voice that was modulated to sound "synthetic but soulful." It’s a masterclass in physical acting that critics at the time mostly ignored because they were too busy calling the movie "mawkish."

The Asimov Connection (and why it’s a bit messy)

The film is based on Isaac Asimov’s short story and the expanded novel The Positronic Man. If you're a sci-fi purist, the movie probably makes your eye twitch.

Asimov was obsessed with the Three Laws of Robotics. The movie? It mentions them in a flashy, slightly confusing sequence at the start and then kind of forgets them.

💡 You might also like: Why the Revolution TV series actually deserved a third season

- The Story: A cold, logical legal battle for rights.

- The Movie: A sweeping romance where a robot wants to get married.

The biggest departure is the love story. In the original text, Andrew Martin (the robot) is driven by an intellectual desire for freedom. In the film, Andrew’s quest for humanity is largely fueled by his love for Portia, played by Embeth Davidtz. It turned a hard sci-fi concept into a "greeting card" movie, according to the legendary Roger Ebert.

Why the Makeup Matters

Despite the mixed reviews, you can't talk about Robin Williams Bicentennial Man without mentioning Greg Cannom. He’s the genius who did the old-age makeup. He actually got an Oscar nomination for it, and it’s easy to see why.

The film covers two centuries.

We see the Martin family age and die while Andrew stays exactly the same. Then, Andrew starts "upgrading" himself. He goes from a shiny NDR-114 unit to a guy wearing silicone skin and artificial hair.

The transition is eerie and beautiful. By the end, the makeup is so thick that Robin’s face is almost a mask again, but a human one this time. It’s a weirdly poetic mirror of the beginning.

What People Missed About the "Corniness"

Is the movie sentimental? Yeah, absolutely. It’s a Chris Columbus film; the man practically invented "heartwarming."

But there’s a darkness there.

Andrew spends 200 years watching everyone he loves wither away. He sees "Little Miss" grow from a child into an old woman and eventually a memory. He watches "Sir" (played by a very stern Sam Neill) pass away.

To become human, Andrew eventually realizes he has to accept the one thing robots aren't built for: obsolescence. He has to choose to die.

That’s heavy stuff for a PG-rated family flick. It’s basically a movie about a man—or a machine—slowly committing suicide by aging so he can be recognized as a person.

2026 Perspective: Was it Ahead of Its Time?

Today, we’re arguing about whether LLMs have "souls" or if they're just "stochastic parrots." Andrew Martin’s legal battle in the film feels way more relevant now than it did in '99.

He wasn't just asking to be "nice." He was asking for the right to own property, to marry, and to have his existence validated by a World Congress.

The film’s failure likely scared studios away from high-concept Asimov adaptations for years. We eventually got I, Robot with Will Smith, but that was an action movie with an Asimov skin. Robin Williams Bicentennial Man was a genuine attempt to film a philosophical treatise on what makes a human, human.

Actionable Takeaways for the Rewatch

If you’re going to revisit this one, don't go in expecting Aladdin.

- Watch the body language. Notice how Robin’s movements change over the "decades." He starts with stiff, hydraulic stops and ends with the slight shakiness of an old man.

- Ignore the "Galatea" subplot. There’s a second robot played by Kiersten Warren that is... a lot. It’s the comic relief the studio insisted on, and it hasn't aged well.

- Focus on the legal scenes. The final speech to the World Congress is where the "real" Asimov themes live. It’s the heart of the movie’s argument.

The film isn't perfect. It’s long (over two hours), it’s slow, and James Horner’s score is doing a lot of heavy lifting to make you cry.

But it’s also one of the bravest performances of Robin Williams' career. He traded his greatest weapon—his face and his frantic energy—for a metal shell and a quiet, dignified performance that still lingers.

Check your local streaming services or digital storefronts; it’s usually available for a few bucks. It’s worth it just to see a version of the future that wasn't a bleak, neon-soaked dystopia. It was a future that was, for lack of a better word, kind.