You’ve probably seen a rough endoplasmic reticulum picture in a biology textbook and thought it looked like a stack of flattened pancakes or maybe a messy pile of ribbons. It’s easily the most distinct part of a cell. While the nucleus gets all the credit for being the "brain," the rough ER is where the actual heavy lifting happens. It’s the factory floor. If the nucleus is the CEO sending out memos, the rough ER is the group of exhausted engineers actually building the product.

Most people look at these images and see static lines. They aren't static. In a living cell, this thing is pulsing, shifting, and constantly vibrating with activity. It’s a massive membrane network that can take up a huge chunk of the cell's internal volume, especially in organs like your pancreas or liver.

Why a Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum Picture Looks So Grainy

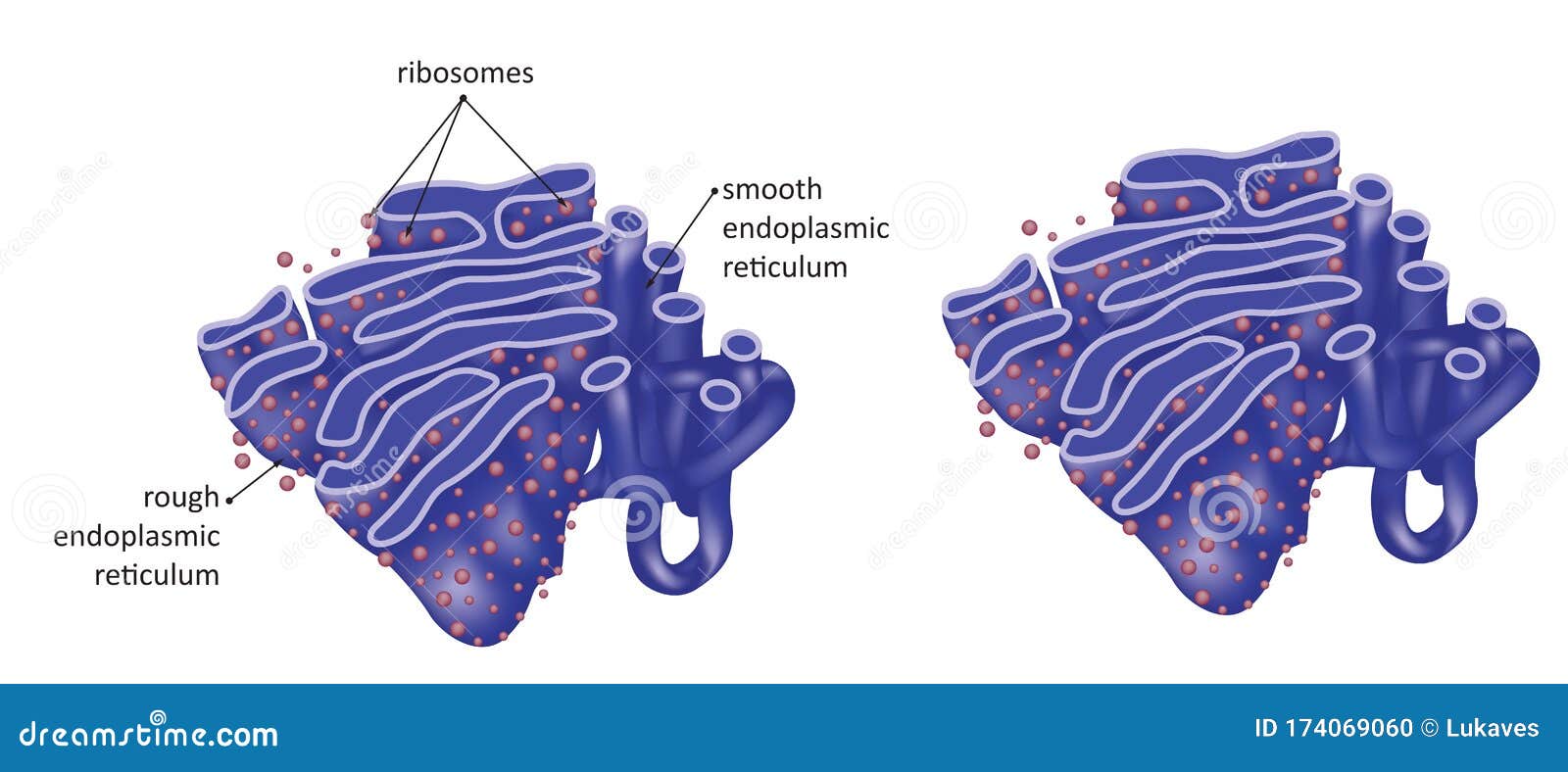

The "rough" part of the name isn't just a creative adjective. When scientists first started using electron microscopes in the mid-20th century, they noticed that some parts of the ER looked smooth—like polished tubes—while other parts were studded with tiny dots. Those dots are ribosomes.

These ribosomes are the reason any rough endoplasmic reticulum picture looks like it has a bad case of the measles. They are protein-making machines. They dock onto the surface of the ER membrane and pump freshly made proteins directly into the interior space, which we call the lumen.

It's pretty wild.

The membrane itself is a phospholipid bilayer, just like the outer wall of the cell. But it’s folded so tightly that it creates these narrow alleys called cisternae. This isn't just to look cool; it’s about surface area. The more folds you have, the more ribosomes you can fit. More ribosomes mean more protein. If you’re looking at a picture of a cell from a silk gland in a caterpillar or a human plasma cell making antibodies, the rough ER will look absolutely massive because those cells are basically protein-exporting machines.

The Geography of the Cell: Where the ER Sits

Location matters. If you find a high-resolution rough endoplasmic reticulum picture, you’ll notice it’s almost always snuggled right up against the nucleus.

In fact, the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope is actually continuous with the rough ER. They are literally the same piece of fabric. This makes total sense from an efficiency standpoint. The nucleus sends out instructions in the form of mRNA. Those instructions don’t have to travel across the city; they just walk out the door and immediately hit the ribosomes waiting on the rough ER.

It's Not All About Proteins

While everyone focuses on protein synthesis, the rough ER is also a quality control center.

Inside the lumen, proteins aren't just floating around. They’re being folded. Chaperone proteins—yes, that is the real scientific term—grab the new protein chains and twist them into the correct 3D shapes. If a protein is folded wrong, the ER detects it. It’s like a factory inspector. If the "misfold" is too bad, the ER triggers a process called ERAD (Endoplasmic-Reticulum-Associated Degradation), which basically sends the broken protein to the cell's "shredder," the proteasome.

Identifying Different Types of Rough ER in Micrographs

Not every rough endoplasmic reticulum picture looks the same. Depending on the type of microscopy used, you’ll see different things.

- TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy): This gives you that classic 2D "cross-section" look. You see thin, dark lines (the membranes) covered in even darker dots (the ribosomes). This is what you find in most academic papers.

- SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy): This provides a 3D view of the surface. It looks more like a landscape of rolling hills or a dense forest.

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Scientists use glowing dyes to highlight the ER in living cells. Instead of grainy dots, you see a glowing green or red web that stretches from the nucleus out toward the edges of the cell.

Keith Porter, a pioneer in cell biology, was one of the first to really map this out in the 1940s. Before him, people thought the inside of a cell was just a watery soup. His early images proved that the cell has a complex, organized internal architecture.

What Happens When the Rough ER Fails?

When you look at a rough endoplasmic reticulum picture, you're looking at the foundation of health. If those membranes get crowded or the folding process starts to fail, the cell enters a state called "ER Stress."

✨ Don't miss: Can You Use Tretinoin While Pregnant? Why Most People Get This Wrong

This isn't just a minor inconvenience.

Chronic ER stress is a major player in diseases like Type 2 diabetes. In your pancreas, the beta cells are responsible for making insulin (a protein). If they are forced to make too much insulin too fast, the rough ER gets overwhelmed. Proteins start misfolding. The cell panics. Eventually, the cell might even kill itself to prevent the "toxic" misfolded proteins from spreading.

Researchers like Dr. Randal Kaufman have spent decades studying how this stress response—officially known as the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)—decides whether a cell lives or dies. It’s a delicate balance. A little stress helps the cell adapt. Too much, and the whole system crashes.

The Golgi Connection

You can’t really talk about a rough endoplasmic reticulum picture without mentioning its partner, the Golgi apparatus.

Once a protein is folded and tagged with sugar chains (glycosylation) in the ER, it gets packed into a tiny bubble called a vesicle. This vesicle pinches off the ER membrane and floats over to the Golgi. If the ER is the factory floor, the Golgi is the shipping and receiving department. It adds the "mailing labels" to the proteins so they know whether to go to the cell membrane, the lysosomes, or out of the cell entirely.

Surprising Nuances in ER Appearance

Sometimes the ER isn't "rough" or "smooth" in a binary way. There are transitional zones.

In some cells, you’ll see "ER exit sites" where the ribosomes are sparse, and the membrane starts to bud off. Also, the ratio of rough to smooth ER changes based on what you’re doing. If you start drinking a lot of alcohol, your liver cells will actually expand their smooth ER to help detoxify the ethanol. If you’re a bodybuilder, your muscle cells' sarcoplasmic reticulum (a specialized version of the ER) is constantly working to manage calcium for contractions.

Biology is incredibly plastic. The pictures we see in books are just a snapshot of one moment in a very busy life.

How to Analyze a Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum Picture Yourself

If you’re looking at a micrograph for a class or a research project, don’t just look at the dots.

First, look for the nucleus. The rough ER will be the stuff wrapped around it like a scarf. Second, check the spacing. In healthy cells, the cisternae are usually neatly packed. If they look swollen or "vacuolated," that’s a sign the cell was under intense stress or dying when the picture was taken.

Finally, look for the ribosomes. If they are falling off the membrane—a process called "de-studding"—it usually means the cell's energy levels (ATP) were crashing.

Actionable Insights for Students and Researchers

- Verify the scale bar: Micrographs can be misleading. Always look at the micron ($\mu m$) or nanometer ($nm$) scale to understand the actual size of the structures.

- Contrast the ER with the Golgi: People often confuse the two. Remember: the rough ER has ribosomes and is connected to the nucleus; the Golgi is usually further away and lacks the "grainy" texture.

- Check the cell type: If you’re looking at a "typical" cell, you’re seeing a generalization. Always ask if the picture is from a specialized cell (like a neuron or a goblet cell) because the ER shape will change drastically to fit the function.

- Look for "Whorls": In some pathological states, the rough ER can form circular, onion-like structures. These are often signs of specific protein storage diseases.

Understanding the rough endoplasmic reticulum picture is basically about understanding how life builds itself. Every protein in your body, from the collagen in your skin to the enzymes digesting your lunch, likely spent its "infancy" inside those membrane folds. It's a chaotic, crowded, and incredibly efficient system that keeps you running at a molecular level.