Ever felt like the world is a bit more... alive than the textbooks say? Honestly, most of us have. You're walking down a street, and you just know someone is staring at the back of your head. You turn around. Yep, there they are. It’s a tiny moment, but it’s a moment that technically shouldn't happen if you follow the strict rules of modern materialism.

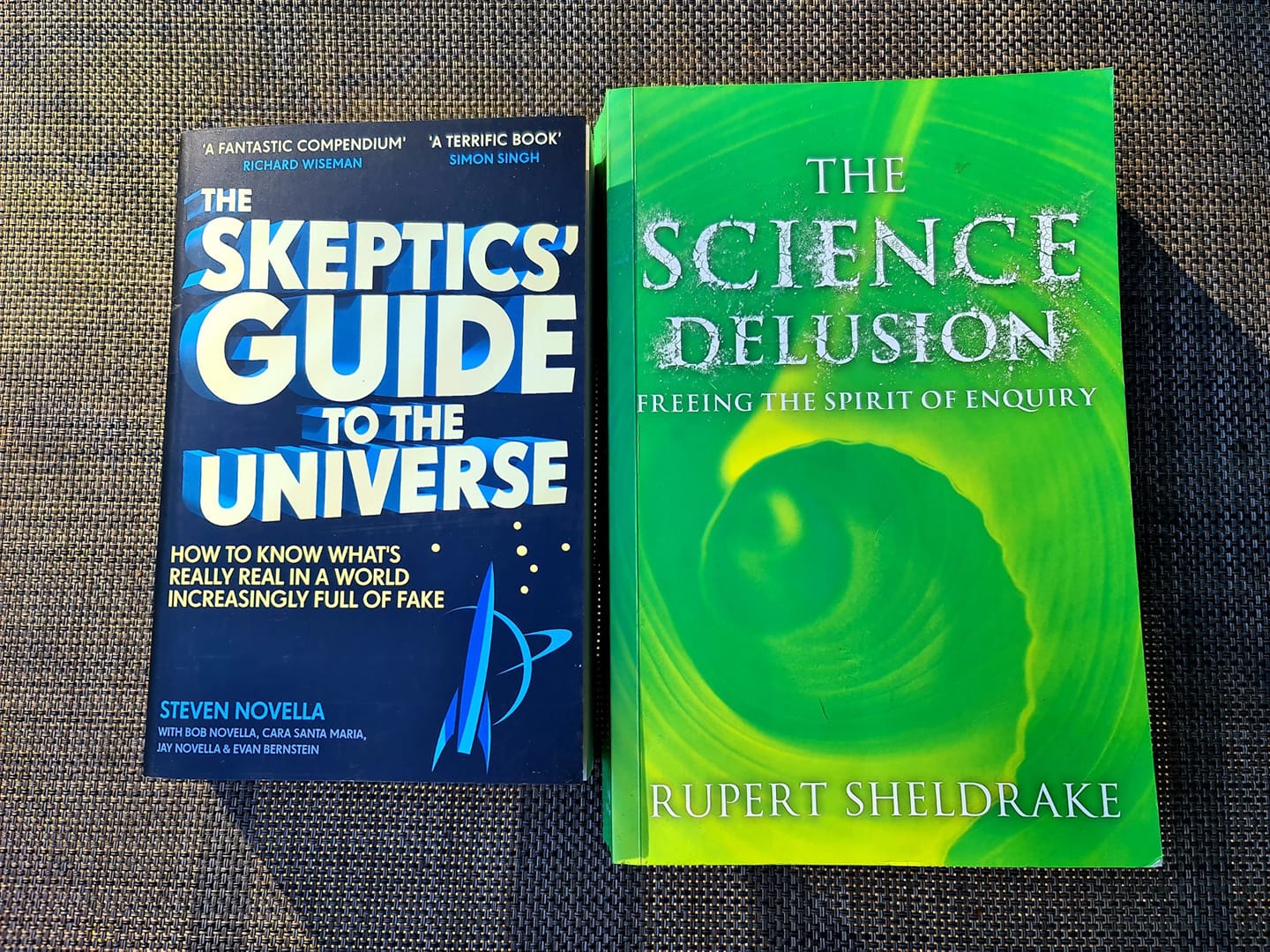

Rupert Sheldrake’s book, The Science Delusion (published as Science Set Free in the US), is basically a massive "Wait a second" aimed at the scientific establishment. He isn't some guy with a tinfoil hat. He’s a Cambridge-educated biologist with a PhD, a former fellow of the Royal Society, and someone who actually knows how to run a lab. But he’s become a bit of a "taboo figure" because he dared to suggest that science has stopped being a method of inquiry and started being a rigid belief system.

The Ten Dogmas: When Science Becomes a Religion

Sheldrake’s main beef is that science has been hijacked by a philosophy called materialism. He argues that scientists have stopped asking questions and started assuming they already have the answers. Basically, he lays out ten "dogmas" that most modern scientists treat as absolute truth, even though there's very little proof for them.

- Nature is mechanical. We’re told the universe is a machine, animals are "lumbering robots," and your heart is just a pump.

- Matter is unconscious. The stars, the rocks, the planets—they’re all dead. Even your own consciousness is just a weird "glitch" or a byproduct of brain activity.

- The laws of nature are fixed. They’ve been the same since the Big Bang and will never change.

- Nature is purposeless. Evolution has no goal. It’s all just random mutations and survival.

- Minds are inside heads. Your thoughts are strictly confined to the physical gray matter inside your skull.

When you look at these points, they feel kind of... bleak. Sheldrake isn't just complaining about the vibe, though. He turns these dogmas into questions. For example, instead of assuming the laws of nature are fixed, he asks: "Are the laws of nature more like habits?" He points out that the "constants" of science, like the speed of light ($c$) or the universal gravitational constant ($G$), actually fluctuate in lab measurements. Instead of investigating why, scientists usually just average the numbers and call the variation "experimental error." It’s a bit like sweepin’ the weird stuff under the rug because it doesn't fit the map.

The Morphic Resonance Idea

If you've heard of Sheldrake, you've probably heard of morphic resonance. This is his big, controversial theory. He suggests there’s a kind of "memory" in nature. If a group of rats in a lab in London learns a new trick, he argues that rats of the same breed in New York should be able to learn it faster, simply because the first group already did.

It’s about "fields" of information. Think of it like a TV set. The TV doesn't contain the show; it tunes into a signal. Sheldrake suggests our brains might be more like receivers than storage units. This would explain how memories persist even when brain cells are replaced, or why certain biological forms (like the shape of a leaf) repeat so consistently across the planet.

Why the "Banned" TED Talk Still Matters

In 2013, Sheldrake gave a TEDx talk titled "The Science Delusion." It was a hit. People loved it. But then, the TED scientific board—under pressure from skeptics like P.Z. Myers and Jerry Coyne—decided to "censor" it by moving it to a hidden part of their website. They claimed it was pseudoscience.

That move backfired spectacularly.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Kitchen Prep Table Island Is Actually the Most Important Tool You Own

It turned a niche talk into a viral sensation. People who didn't even care about biology were suddenly asking why a prestigious organization was so afraid of a biologist questioning whether the speed of light is truly constant. It highlighted the exact point Sheldrake was making: that science can sometimes behave more like a protective priesthood than an open-minded search for truth.

Acknowledging the Skeptics

Look, it’s not all sunshine and morphic fields. The scientific community has a lot of valid reasons to be skeptical. Critics like Steven Rose have argued that Sheldrake’s experiments—like the ones on "the sense of being stared at" or dogs knowing when their owners are coming home—don't hold up under strict peer review.

The biggest hurdle for The Science Delusion is that it’s hard to replicate Sheldrake's findings in a way that satisfies everyone. Mainstream biologists argue that DNA and epigenetic inheritance already explain how traits are passed down, without needing a "mystical" field. They see his work as a "God of the gaps" argument, just filling in the things we don't understand yet with poetic but unproven ideas.

But honestly? Even if Sheldrake is 90% wrong, that 10% of questioning is vital. Science thrives on being poked and prodded. When we stop questioning the "laws" of the universe, we stop being scientists and start being followers.

Real-World Implications of a "Living" Science

If we took Sheldrake's ideas seriously, how would the world change?

- Medicine would get a makeover. We’d stop treating the body like a broken car and start looking at the "field" of the person—their mind, their environment, and their connections.

- Funding would shift. Instead of spending billions on the same materialist tracks, we might put a few million into "fringe" research that actually yields results, like the placebo effect or telepathy.

- Environmentalism would feel different. If we think of the Earth as a living organism (the Gaia hypothesis) rather than a pile of resources, our motivation to protect it becomes intrinsic, not just a matter of survival.

Moving Beyond the Materialist Box

The "delusion" Sheldrake talks about isn't that science is bad. It’s that science is finished. He wants to crack the door open again. He’s inviting us to look at the world with a bit more wonder and a lot more skepticism toward the "experts" who say they have it all figured out.

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just take his word for it. Start by noticing the "unexplained" things in your own life. Do you feel the "morphic resonance" of your family habits? Do you notice when the "fixed" rules of your world seem to bend a little?

Actionable Next Steps:

- Audit your assumptions: Pick one of the "ten dogmas"—like the idea that your mind is only in your brain—and spend a day acting as if the opposite were true.

- Watch the "banned" talk: Search for "Rupert Sheldrake Banned TED Talk" on YouTube. It’s still there, and it’s a great exercise in critical thinking.

- Read the rebuttals: Don't be a one-sided thinker. Look up the critiques by scientists like Jerry Coyne to see where the friction lies. It makes the whole debate much more interesting.

- Conduct your own "Staring" test: Sheldrake has protocols online for simple experiments you can do with a friend to test the "sense of being stared at." It’s a low-stakes way to engage with the scientific method yourself.

The universe is likely much weirder than we’ve been led to believe. Whether you think Sheldrake is a visionary or a heretic, he’s definitely made the conversation a whole lot more fun.