Walk onto any beach and you're stepping on billions of years of history. It feels like grit. It gets into your shoes. It's annoying when it's in your sandwich. But honestly, if you actually look at sand under the microscope, the reality is kind of a shock. Most people think sand is just "tiny rocks." It isn't. Or at least, it isn't only that. Depending on where you are in the world, that handful of beige dust might actually be a collection of miniature tropical shells, volcanic glass shards, or even tiny stars made of calcium.

It's spectacular.

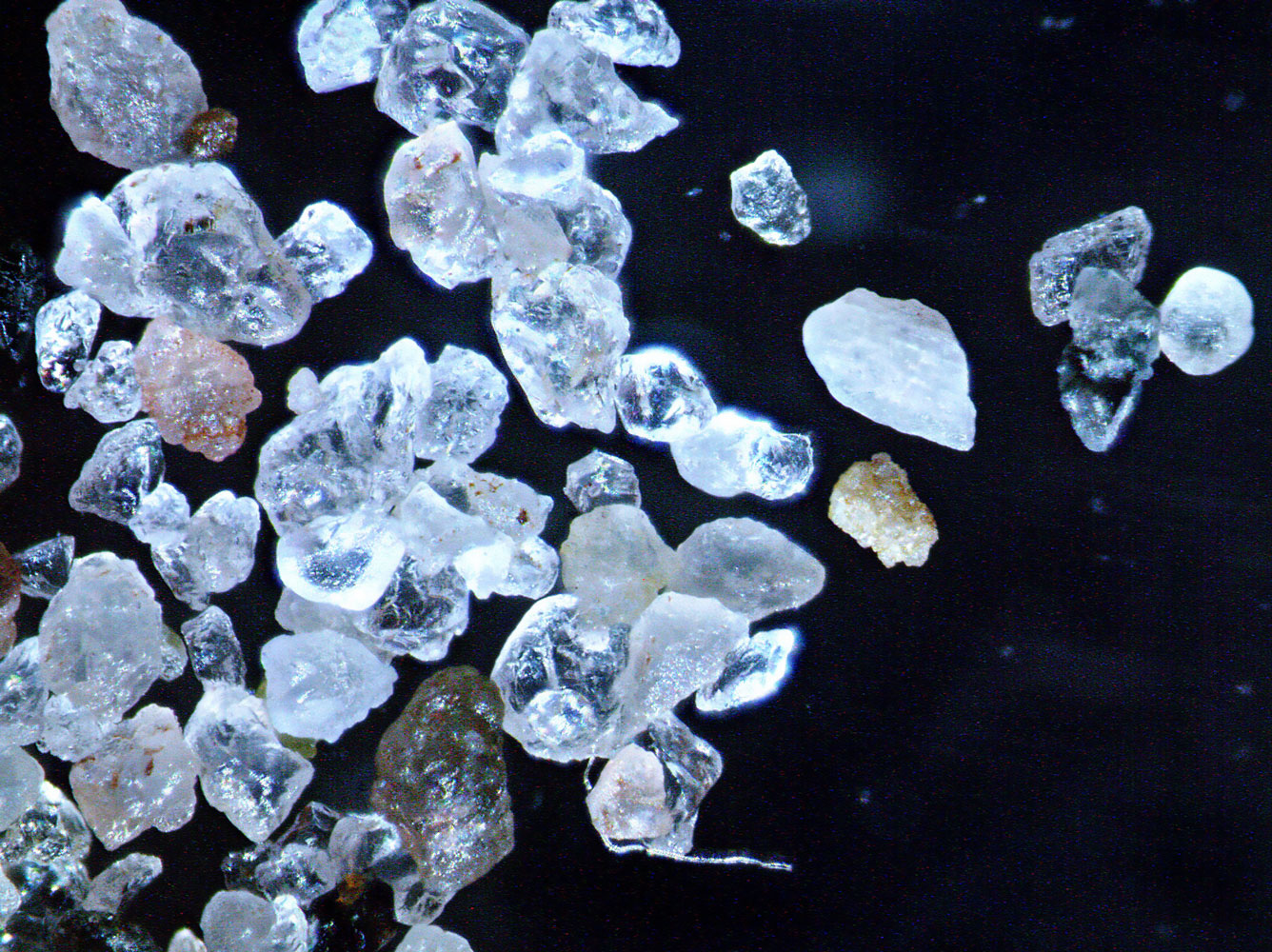

Dr. Gary Greenberg, an author and scientist with a PhD from University College London, has spent years photographing these grains. His work basically changed how we see the ground beneath our feet. When you magnify sand 200 or 300 times, the "beige" disappears. You see spiraling gastropod shells. You see translucent green olivine crystals. You see bits of coral that look like Swiss cheese.

What Sand Under the Microscope Actually Reveals

Every beach tells a different story. If you're looking at sand from a volcanic island like Hawaii, you aren't going to see much quartz. Instead, you'll see sharp, black fragments of basalt or the glassy, olive-green shimmer of olivine. This stuff is "young" in geological terms. It hasn't been tumbled by the waves long enough to become smooth or round. It's jagged. It's aggressive.

Contrast that with a typical Florida beach. There, the sand is mostly "biogenic." That’s a fancy way of saying it used to be alive. You’re looking at the crushed remains of sea urchin spines, bits of clam shells, and the skeletons of foraminifera. Foraminifera—or "forams"—are single-celled organisms that build incredible shells. Some of them, especially in places like Okinawa, Japan, look exactly like five-pointed stars. They call it "Hoshizuna," or Star Sand. Imagine walking on millions of tiny stars. It’s wild.

Then you have the desert. Saharan sand is different because it isn't moved by water; it’s moved by wind. This "aeolian" process acts like a rock tumbler. It knocks the corners off every grain until they are almost perfectly spherical. Under a lens, desert sand often looks like frosted glass marbles. It has a matte finish because of the constant microscopic collisions in the air.

🔗 Read more: Why Words to Mellow Yellow Still Influence How We Think About Color

The Quartz Connection

Most of the sand we see on "boring" brown beaches is quartz. Why quartz? Because it’s tough. While other minerals like feldspar or mica eventually break down into clay or dissolve in the water, quartz is chemically stable and physically hard. It’s the survivor.

If you look at sand under the microscope from a riverbed, the quartz grains are often clear or milky. They look like raw diamonds. Over thousands of years, as they travel from the mountains to the sea, they get smaller and rounder. If the sand looks orange or red, it’s usually because of a thin coating of iron oxide. Basically, the sand is rusting.

Why Some Sand Isn't "Rock" at All

We usually think of geology as something slow and ancient. But sand is where geology happens in real-time. In the Caribbean, much of the white sand is actually fish poop. Specifically, it’s from the Parrotfish. These fish munch on coral to get to the algae inside. Their powerful pharyngeal teeth grind the calcium carbonate skeleton into a fine powder. A single large Parrotfish can produce hundreds of pounds of white sand per year.

Next time you’re lying on a pristine white beach in the Bahamas, remember that you’re likely tanning on the digestive output of a colorful fish.

There's also "Ooid" sand. This is fascinating stuff. In shallow, warm tropical waters, calcium carbonate can precipitate out of the water and coat a tiny grain of debris, like a pearl. This creates perfectly round, white spheres called ooids. They look like tiny snowballs under a microscope.

✨ Don't miss: Birthday Wishes to My Pastor: How to Say Something That Actually Matters

The Forensic Power of a Single Grain

Geologists and forensic scientists use sand to solve mysteries. Because the mineral composition of sand is so specific to a location, it’s like a fingerprint. If a suspect has sand in their car carpet, a scientist can look at it under a microscope and potentially say, "This didn't come from the local beach; this came from a specific quarry 50 miles away."

They look for:

- Mineralogy: Is there magnetite? Garnet? Glauconite?

- Sorting: Are all the grains the same size (well-sorted) or a mix of huge and tiny (poorly sorted)?

- Roundness: Is it "sub-angular" or "well-rounded"?

- Inclusions: Are there tiny bubbles or other minerals trapped inside the grain?

It’s a level of detail that’s invisible to the naked eye but glaringly obvious under a simple 40x stereo microscope.

How to See This Yourself (Without a Lab)

You don't need a $10,000 microscope to see this. You can actually get a decent look with a cheap 10x or 20x jeweler’s loupe. But if you want the "jewelry box" effect, you need a digital microscope or a stereo microscope with top-down lighting.

The trick is the light.

If you shine light through the sand (bottom lighting), it just looks like dark blobs. You need to bounce light off the top of the grains. This makes the crystals sparkle and the shell fragments pop. It’s the difference between looking at a stained-glass window in the dark and seeing it hit by the morning sun.

Practical steps for your own "Sand Safari":

- Collect widely: Don't just get sand from the water's edge. Grab some from the dunes, the high-tide line, and even nearby riverbeds.

- Wash and dry: If it’s sea sand, rinse it with fresh water to get the salt off. Salt crystals are cool to look at, but they can cloud the view of the actual grains. Let it dry completely.

- Use a black background: Spread a few grains—not a pile, just a few—on a matte black card. This makes the colors of the minerals stand out.

- Experiment with magnets: Take a strong magnet and run it under your sand sample. If you see grains dancing or sticking, you’ve found magnetite. These grains often look like metallic, dark-grey or black geometric shapes under the lens.

The Problem with Modern Sand

There's a darker side to sand under the microscope these days. Microplastics. Almost every beach sample now contains tiny, brightly colored fibers or jagged shards of plastic. They stand out because their colors—hot pink, neon blue, electric green—don't really exist in the mineral world.

It’s a bit depressing. You’re looking for a beautiful piece of ancient zircon and you find a fragment of a straw.

But even with the pollution, the natural diversity is staggering. You might find "heavy minerals" like garnet, which looks like crushed rubies, or staurolite, which can form tiny crosses. In some parts of the UK, you can find "heavy" sands that are almost entirely dark purple because of the garnet concentration.

Getting the Most from the Experience

The biggest mistake people make is thinking all sand is the same. It's really not. The sand on the volcanic beaches of Iceland is a world away from the crushed coral of the Maldives or the quartz-rich "singing sands" of Lake Michigan. Yes, some sand actually "sings" or squeaks when you walk on it because the grains are so uniform in size and shape that they vibrate together.

If you’re a hobbyist, start a "sand library." Small glass vials with labels are all you need. It’s a way of collecting the world that doesn't cost anything and takes up almost no space.

✨ Don't miss: Black Moon August 22: What’s Actually Happening in the Night Sky

Actionable Next Steps:

- Get a Loupe: Buy a 30x triplet jeweler's loupe. It's the cheapest way to transform your next beach trip.

- Check Your Local Geology: Look up a "lithology map" of your area. It will tell you what kind of rocks are nearby, which tells you what to expect in your local sand.

- Join a Community: Groups like the International Sand Collectors Society (yes, that’s a real thing) have "sand swaps" where people mail each other samples from across the globe.

- Focus on Lighting: If you use a microscope, use an external LED gooseneck lamp to hit the sand from the side. This creates shadows that reveal the texture of the grains.

Looking at sand reminds you that the "big" world is just a collection of very small, very beautiful things. It's a perspective shift. You stop seeing a "beach" and start seeing a massive, outdoor museum of planetary history.