Ever tried to find a deed in the middle of a Friday afternoon? It's a headache. Most people think they can just Google an address and see the owner's name, their mortgage balance, and maybe their middle name. Honestly, it doesn't work like that in Santa Barbara County. California privacy laws and the way the Clerk-Recorder’s office handles Santa Barbara County real estate records make it a bit of a scavenger hunt.

If you’re looking for a quick "Zillow-style" experience, you’re going to be disappointed. The official portals are built for legal compliance, not for speed.

The Gap Between the Assessor and the Recorder

You've got to understand the "Big Two." People use these terms interchangeably, but they are totally different animals. The County Assessor is all about the money. They care about how much your house is worth so they can send you a tax bill. If you want to know the "Assessed Value" or find a parcel map, you head to the Assessor.

The County Recorder? That’s where the history lives.

The Recorder is the custodian of every "event" that happens to a piece of dirt. A sale, a new loan, a lien from a contractor you didn't pay—it all gets stamped and filed there. Joseph E. Holland wears both hats (he's the Clerk-Recorder and the Assessor), but the databases don't always talk to each other in real-time.

💡 You might also like: Online Taxes for Free: Why You Should Never Pay to File Again

Basically, the Recorder's office is the "source of truth" for ownership. If a deed isn't recorded there, legally, did the sale even happen? In the eyes of the county, probably not.

How to Actually Find Santa Barbara County Real Estate Records

Most of the modern stuff—anything from 1975 to today—is sitting in the Official Records Search. It’s a self-service system. You can’t search by address. Yeah, you read that right. You have to search by name (Grantor/Grantee) or by the specific document number.

If you only have an address:

- Go to the Assessor’s website first.

- Plug in the address to find the Assessor’s Parcel Number (APN) and the current owner's name.

- Take that name over to the Recorder’s portal.

- Search the name to find the actual Grant Deed.

It's a two-step dance. If you’re looking for the older stuff, like a gold-rush era map or a deed from 1940, you’re looking at the Historical Index (1931 to 1974). Anything before 1931? You might literally have to go to the Hall of Records at 1100 Anacapa Street.

The Hall of Records is a stunning building, but let's be real, nobody wants to drive downtown and pay for parking just to look up a lien.

The Price of Information

Nothing is free. Searching the index is usually fine, but if you want to actually see the document or download a copy, the county wants its cut.

💡 You might also like: How can I get donations from companies without getting ignored?

- Standard Copy: $10 per document.

- Certified Copy: $12 per document.

- Recording a new deed: Usually starts at $14 for the first page, plus a $75 "Building Homes and Jobs Act" fee that catches everyone off guard.

If you’re doing a massive title search for a commercial project, these costs add up fast. Most pros use subscription services to bypass the per-document fee, but for a regular person just trying to see if their neighbor has a massive mortgage, the $10 hit is the standard entry fee.

Common Myths About Property Records

"I paid off my mortgage, so the county will send me my deed."

Nope. Not how it works. When you pay off a loan, the bank records a "Reconveyance." That document proves the loan is dead. The original deed you got when you bought the house is still the valid one; the Reconveyance just "clears" it.

"Public records mean I can see the sale price of every house."

Sorta. While the Documentary Transfer Tax is public (it’s $1.10 per $1,000 of the sale price), some savvy buyers hide the tax amount on the face of the deed to keep the price private. You have to do the math backward from the tax affidavit if it's filed separately. It's a total "insider" move.

Navigating the Physical Offices

If the website crashes—which happens—you have two main spots to visit.

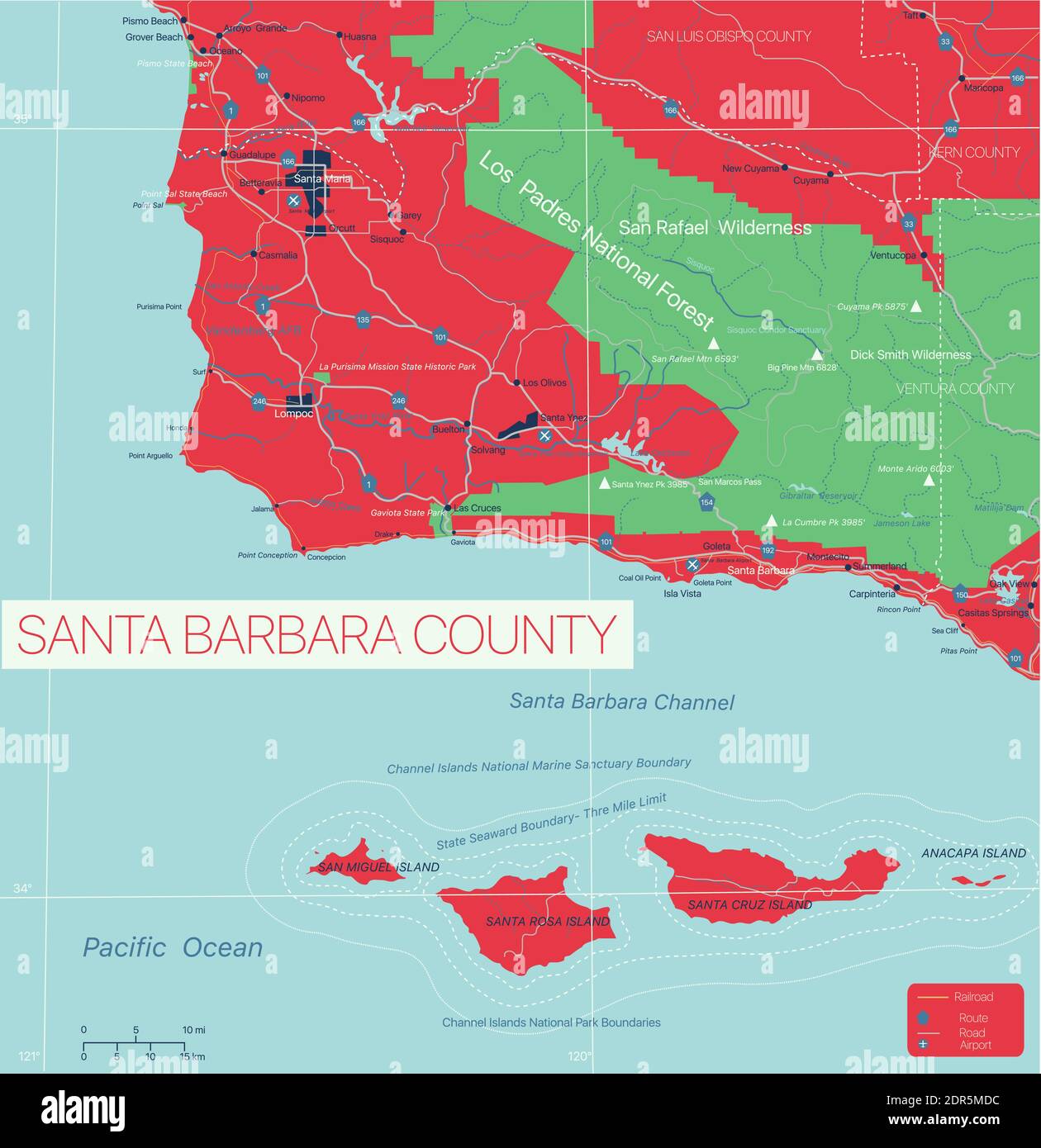

- Santa Barbara (South County): 1100 Anacapa St., Hall of Records. This is right by the courthouse.

- Santa Maria (North County): 511 Lakeside Parkway, Suite 115.

They’re open 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., but honestly, don’t show up at 4:15 p.m. and expect to get a title search done. They usually stop processing new recordings or deep searches about 30 minutes before the doors lock.

✨ Don't miss: American Dollar to Danish Krone: Why the DKK Is More Than Just a Euro Clone

Actionable Steps for Your Search

If you're ready to dig into Santa Barbara County real estate records, don't just wing it.

First, get your APN from the Assessor's map. It’s a three-part number (like 000-000-000) that acts like a social security number for the land. With that, you can verify zoning via the Planning and Development interactive maps to see if you can actually build that ADU you've been dreaming about.

Second, check for "Lis Pendens" or "Notices of Default." If you're looking to buy a property, these are the red flags. A Lis Pendens means there’s a lawsuit involving the property. A Notice of Default means the owner is behind on payments. These appear in the Recorder's index long before they hit the news or real estate sites.

Finally, if you find a document that looks like gibberish—and many legal descriptions do—don't ask the Clerk for help interpreting it. By law, they can't give legal advice. You'll need a title officer or a real estate attorney for that.

Start your search at the Official Records portal and make sure you have a credit card ready if you need to download the PDF. If the name search yields too many results, filter by "Recording Date" to narrow down the specific transaction you're looking for.